Python’s Parallel Future: A Deep Dive into the New Era of Concurrency Without the GIL

The Next Leap in Python Performance: Unlocking True Multicore Parallelism

For years, Python has reigned as one of the world’s most popular programming languages, celebrated for its simplicity, readability, and vast ecosystem. However, it has always carried a well-known performance asterisk: the Global Interpreter Lock (GIL). This mechanism, while crucial for Python’s design, has historically prevented threads from achieving true parallelism on multi-core processors for CPU-bound tasks. This limitation has been a significant bottleneck for high-performance computing, data science, and AI workloads. The latest python news, however, signals a monumental shift in this landscape.

A groundbreaking development is on the horizon for the Python community. An experimental feature, proposed and accepted under PEP 703, introduces the ability to build Python in a “free-threaded” mode, effectively making the GIL optional. This change is poised to redefine Python’s performance capabilities, allowing developers to harness the full power of modern hardware for computationally intensive applications. This article provides a comprehensive technical breakdown of this historic change, exploring what the optional GIL means, how it works, its real-world implications, and how developers can prepare for a new era of Python concurrency.

Section 1: Understanding the Global Interpreter Lock and the New Free-Threaded Mode

To appreciate the magnitude of this change, it’s essential to first understand the role the GIL has played in Python’s history and what its optional removal entails.

What is the Global Interpreter Lock (GIL)?

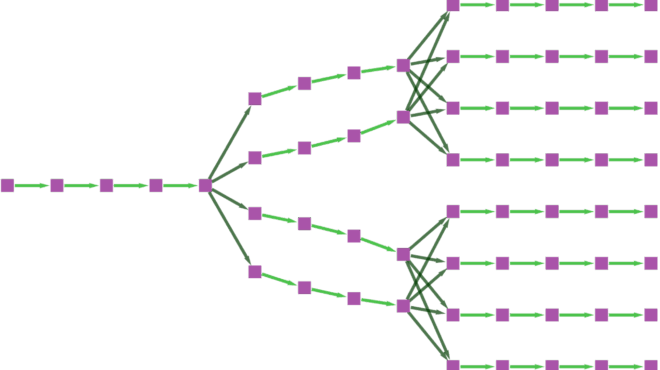

The Global Interpreter Lock is a mutex (a mutual exclusion lock) that protects access to Python objects, preventing multiple native threads from executing Python bytecode at the same time within a single process. In simpler terms, even if you have a machine with 16 cores and you spawn 16 Python threads to perform a calculation, the GIL ensures that only one of those threads is actually executing Python code at any given instant. The other threads are forced to wait their turn.

The GIL was introduced in the early days of Python to simplify memory management. CPython’s memory management relies on a system called reference counting. The GIL ensures that these reference counts aren’t corrupted by two threads trying to modify them simultaneously, which would lead to memory leaks or incorrect deallocation. It also made writing C extensions for Python much simpler, as extension authors didn’t have to worry about complex thread-safety issues, contributing to Python’s rich library ecosystem.

However, this simplicity came at a cost. For I/O-bound tasks (like waiting for a network request or reading a file), the GIL is not a major issue. Python threads can release the GIL while waiting, allowing other threads to run. But for CPU-bound tasks (like complex mathematical computations, data processing, or machine learning model training), the GIL becomes a significant performance bottleneck, effectively limiting a Python process to a single CPU core.

The Big Change: An Optional, Free-Threaded Python

The latest python news, driven by PEP 703, introduces a new compile-time flag (e.g., --disable-gil). When Python is built with this flag, it produces an interpreter that does not have a Global Interpreter Lock. Key points to understand about this change include:

- It’s Optional: The standard distribution of Python that most people download and use will still include the GIL by default. This ensures maximum backward compatibility with the existing ecosystem of libraries and C extensions.

- It’s Experimental: This feature is being introduced as an experimental option. It requires a custom build of Python and is intended for developers and library authors to begin testing, adapting, and exploring its potential.

- It Enables True Parallelism: In a free-threaded build, multiple threads within a single process can execute Python bytecode on different CPU cores simultaneously. This is the paradigm shift that unlocks true multi-core performance for CPU-bound workloads.

Section 2: How Free-Threading Works: A Technical Breakdown

Simply removing the GIL is not a trivial task. It requires a fundamental re-architecture of CPython’s internals, particularly its memory management and object model, to ensure thread safety without a single, coarse-grained lock.

Beyond the GIL: New Concurrency Mechanisms

To operate safely without a global lock, the free-threaded build introduces several sophisticated mechanisms:

- Finer-Grained Locking: Instead of one lock for the entire interpreter, locks are applied to specific, individual data structures when they need to be mutated. This allows different threads to work on different objects concurrently without conflict.

- Biased Reference Counting: This is an optimization of Python’s standard reference counting system. It’s designed to be faster in the common case where an object is primarily accessed by a single thread, reducing the overhead of atomic operations required for thread-safe reference counting.

- Immortal Objects: Certain fundamental objects that are created once and never destroyed (like

None,True, andFalse) are marked as “immortal.” This allows the interpreter to skip reference counting for them entirely, providing a small performance boost.

The Performance Trade-off: A Tale of Two Workloads

The absence of the GIL introduces a new performance dynamic. While it dramatically improves multi-threaded CPU-bound performance, it can introduce a slight overhead for single-threaded code. The new thread-safe memory management mechanisms are inherently more complex than the GIL-protected version, which can result in a performance penalty of a few percent for code that doesn’t use multiple threads.

Let’s illustrate with a practical code example. Consider a CPU-intensive task like processing a list of numbers.

import time

import threading

from concurrent.futures import ThreadPoolExecutor

# A sample CPU-bound function

def heavy_computation(n):

"""A function that simulates a heavy CPU workload."""

count = 0

for i in range(n):

count += i

return count

def run_threaded_benchmark(num_threads, work_items):

"""Runs the computation using a thread pool."""

start_time = time.time()

with ThreadPoolExecutor(max_workers=num_threads) as executor:

# Each work item is a call to heavy_computation

futures = [executor.submit(heavy_computation, 10**7) for _ in range(work_items)]

results = [f.result() for f in futures]

end_time = time.time()

return end_time - start_time

if __name__ == "__main__":

# In standard Python with the GIL

# Increasing threads from 1 to 4 will show almost no speedup.

duration_1_thread_gil = run_threaded_benchmark(1, 4)

duration_4_threads_gil = run_threaded_benchmark(4, 4)

print(f"Standard Python (with GIL):")

print(f" - 1 Thread: {duration_1_thread_gil:.4f} seconds")

print(f" - 4 Threads: {duration_4_threads_gil:.4f} seconds")

print(f" - Speedup: {(duration_1_thread_gil / duration_4_threads_gil):.2f}x")

# --- Hypothetical Results in Free-Threaded Python ---

# In a free-threaded build on a 4+ core machine, we'd expect near-linear scaling.

# Note: The single-threaded version might be slightly slower due to overhead.

hypothetical_duration_1_thread_nogil = duration_1_thread_gil * 1.05 # ~5% overhead

hypothetical_duration_4_threads_nogil = hypothetical_duration_1_thread_nogil / 3.8 # Near 4x speedup

print("\nHypothetical Free-Threaded Python (no GIL):")

print(f" - 1 Thread: {hypothetical_duration_1_thread_nogil:.4f} seconds (with overhead)")

print(f" - 4 Threads: {hypothetical_duration_4_threads_nogil:.4f} seconds")

print(f" - Speedup: {(hypothetical_duration_1_thread_nogil / hypothetical_duration_4_threads_nogil):.2f}x")

In the example above, standard Python with the GIL would show that running the task with four threads is no faster than with one. In contrast, the hypothetical free-threaded version would demonstrate a significant speedup, approaching 4x on a four-core machine. This is the core benefit of the optional GIL.

Section 3: Real-World Implications for Python Developers

This change is not just an academic exercise; it has profound, practical implications across various domains where Python is a key player.

A New Dawn for AI, ML, and Data Science

The fields of Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, and Data Science are prime beneficiaries. Many tasks in these domains are CPU-intensive:

- Data Preprocessing: Operations like cleaning, transforming, and feature engineering on large datasets with libraries like Pandas can be parallelized across cores.

- Numerical Computing: Scientific simulations and complex calculations performed with NumPy or SciPy can leverage multi-threading for massive speedups.

- Model Inference: Running predictions with trained models on a CPU can be done in parallel, significantly increasing the throughput of a single server process.

Imagine a data pipeline that processes millions of text documents. With a free-threaded Python, you could spawn threads to handle batches of documents concurrently, drastically reducing the total processing time—all within one memory space, simplifying data sharing compared to multi-processing.

Impact on Web Development and Backend Systems

For decades, Python web frameworks have relied on multi-processing models to scale. Servers like Gunicorn or uWSGI spawn multiple independent Python processes to handle concurrent requests, with each process being bound by the GIL. This model works but has drawbacks, such as higher memory consumption (each process loads the entire application) and complexity in sharing state between processes.

A free-threaded Python could enable a shift towards a multi-threaded server model within a single process. This could lead to lower memory footprints and more efficient use of shared resources like database connection pools and in-memory caches, potentially simplifying deployment architectures.

The C-Extension Ecosystem Challenge

The single biggest hurdle to widespread adoption is the vast ecosystem of C extensions. Popular libraries like NumPy, Pandas, SciPy, and many others are written in C for performance and have historically relied on the GIL for thread safety. In a free-threaded world, these libraries are no longer automatically safe.

This means a massive community effort will be required to audit and update these critical libraries to be thread-safe without the GIL. This involves adding explicit locking where necessary and adopting new APIs. Until a library is certified as “free-threaded safe,” using it in a multi-threaded context in a no-GIL build could lead to data corruption and crashes. This migration will be a gradual process, and developers must be vigilant about the compatibility of their dependencies.

Section 4: Adopting Free-Threaded Python: Best Practices and Recommendations

Given that this is an experimental and significant change, developers should approach it with a clear strategy.

When Should You Consider the No-GIL Build?

The free-threaded build is not a silver bullet. Here’s a guide to help you decide when it might be appropriate:

- Ideal Use Cases: Applications that are heavily CPU-bound and can be easily parallelized with threads. This includes scientific computing, data analysis pipelines, and CPU-based AI inference servers. It’s particularly beneficial when you have control over your entire dependency stack or can verify that all your libraries are thread-safe.

- Proceed with Caution: General-purpose applications, especially those with a large number of third-party dependencies that may not yet be thread-safe. For now, production systems should stick with the default GIL-enabled Python unless a specific, well-understood performance bottleneck can be solved by free-threading.

- Poor Fit: Applications that are primarily I/O-bound or single-threaded. These workloads will not see a benefit and may even experience a slight performance degradation due to the overhead of the new concurrency mechanisms.

Preparing Your Code for a GIL-less Future

Even if you don’t plan to use the free-threaded build immediately, it’s wise to start writing more thread-aware code. The GIL can sometimes hide subtle race conditions in pure Python code.

For example, consider a simple class that is not thread-safe:

import threading

class UnsafeCounter:

def __init__(self):

self.count = 0

def increment(self):

# This operation is not atomic and can cause a race condition

self.count += 1

# To make it thread-safe, you must use a lock

class SafeCounter:

def __init__(self):

self.count = 0

self._lock = threading.Lock()

def increment(self):

with self._lock:

# This block is now atomic, preventing race conditions

self.count += 1

Without the GIL, the UnsafeCounter would produce incorrect results when multiple threads call increment() concurrently. The SafeCounter demonstrates the explicit locking that becomes essential. Developers should start auditing their code for such patterns and adopting explicit locking for shared mutable state.

Conclusion: A New Chapter for Python

The introduction of an optional, free-threaded Python is arguably one of the most significant developments in the language’s recent history. It directly addresses Python’s most persistent performance limitation and opens the door to a new class of high-performance, concurrent applications. While the road to full ecosystem adoption will be long and challenging, this is a clear and powerful statement about Python’s future.

For developers, this python news is a call to action: to understand the trade-offs, to begin writing more thread-conscious code, and to watch as the ecosystem evolves. The GIL is not gone, but its monopoly on Python concurrency is ending. This change ensures that Python will not only maintain its dominance as a language of simplicity and productivity but will also become a true powerhouse for parallel computing in the years to come.