Python News: Mastering Concurrency for High-Performance API Integration

Unlocking High-Performance Python: A Deep Dive into Concurrency for Modern APIs

In today’s interconnected digital landscape, Python applications are increasingly reliant on external APIs for everything from financial data and machine learning models to social media integration and web services. This reliance introduces a significant performance challenge: network latency. A standard, synchronous Python application executes tasks one by one. When it makes an API call, it sits idle, waiting for the server to respond before moving on. For applications that need to make dozens or even hundreds of such calls, this waiting time accumulates into a major bottleneck, leading to sluggish performance and poor user experience. This is a recurring topic in python news and developer forums, as teams seek to build faster, more responsive systems.

The solution lies in concurrency—the art of structuring a program to handle multiple tasks at once. By leveraging concurrency, a Python application can initiate multiple API requests simultaneously, using the idle waiting time from one request to make progress on another. This article provides a comprehensive technical guide to understanding and implementing concurrency in Python. We will explore the fundamental concepts, compare the two primary models for I/O-bound tasks—threading and asyncio—and provide practical, real-world code examples for building high-performance API clients. By the end, you’ll have the knowledge to transform your I/O-bound applications from sequential crawlers into parallel sprinters.

The Concurrency Conundrum in Python: Why and When to Go Parallel

Before diving into code, it’s crucial to understand the “why” behind concurrency in Python. The language’s design, particularly the Global Interpreter Lock (GIL), dictates which concurrency model is appropriate for a given problem. Making the wrong choice can lead to more complex code with no performance benefit, or even worse performance.

I/O-Bound vs. CPU-Bound: The Fundamental Divide

Every performance bottleneck in an application can be broadly categorized into one of two types:

- I/O-Bound Tasks: These are tasks where the program spends most of its time waiting for an external resource. Examples include making a network request to an API, querying a database, or reading/writing from a disk. The CPU is largely idle during these operations. This is the perfect scenario for concurrency models like

threadingandasyncio. - CPU-Bound Tasks: These are tasks that are limited by the speed of the CPU. The program is actively performing intensive calculations. Examples include complex mathematical computations, video encoding, or large-scale data transformations. For these tasks, true parallelism is required, which in Python means using the

multiprocessingmodule to bypass the GIL.

This article focuses exclusively on I/O-bound problems, as they are the most common bottleneck when interacting with external APIs.

The Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) Explained

The GIL is a mutex (a locking mechanism) that protects access to Python objects, preventing multiple native threads from executing Python bytecodes at the same time within a single process. In simpler terms, even on a multi-core processor, only one thread can be executing Python code at any given moment. This makes standard Python threading ineffective for speeding up CPU-bound tasks.

However, the GIL is released by a thread when it performs a blocking I/O operation. While one thread is waiting for a network response, the Python interpreter can switch to another thread and run its code. This creates the illusion of parallelism and provides a massive performance boost for I/O-bound applications. This is precisely why both threading and asyncio are so effective for API integration.

Choosing Your Weapon: A Practical Guide to `threading` and `asyncio`

Python offers two excellent concurrency models for I/O-bound tasks. While they achieve similar goals, their approach, syntax, and scalability characteristics are quite different. Choosing the right one depends on your project’s complexity and requirements.

The Classic Approach: `threading` for Simplicity and Integration

The `threading` module uses pre-emptive multitasking. The operating system is in charge of switching between threads, which can happen at any time. This model is often easier to grasp for developers new to concurrency and integrates well with existing blocking libraries. The modern way to use `threading` is with the `concurrent.futures.ThreadPoolExecutor`, which provides a high-level interface for managing a pool of worker threads.

Let’s imagine we need to fetch the current price for a list of stock tickers from a financial API. A synchronous approach would be painfully slow.

import time

import requests

# A mock API function that simulates network latency

def fetch_stock_price(ticker):

print(f"Fetching price for {ticker}...")

time.sleep(1) # Simulate 1-second network delay

price = 100 + hash(ticker) % 20 # Generate a fake price

print(f"Finished fetching price for {ticker}")

return {"ticker": ticker, "price": price}

# Synchronous execution

tickers = ["AAPL", "GOOG", "MSFT", "AMZN", "TSLA"]

start_time = time.time()

results = [fetch_stock_price(ticker) for ticker in tickers]

end_time = time.time()

print(f"\nSynchronous results: {results}")

print(f"Total time taken (Synchronous): {end_time - start_time:.2f} seconds")

# Expected output: Total time taken is ~5 seconds

Now, let’s accelerate this using `ThreadPoolExecutor`.

import time

import requests

from concurrent.futures import ThreadPoolExecutor, as_completed

# Using the same mock function as above

def fetch_stock_price(ticker):

print(f"Fetching price for {ticker}...")

time.sleep(1)

price = 100 + hash(ticker) % 20

print(f"Finished fetching price for {ticker}")

return {"ticker": ticker, "price": price}

tickers = ["AAPL", "GOOG", "MSFT", "AMZN", "TSLA"]

start_time = time.time()

results = []

with ThreadPoolExecutor(max_workers=5) as executor:

# Submit all tasks to the pool

future_to_ticker = {executor.submit(fetch_stock_price, ticker): ticker for ticker in tickers}

for future in as_completed(future_to_ticker):

results.append(future.result())

end_time = time.time()

print(f"\nThreading results: {results}")

print(f"Total time taken (Threading): {end_time - start_time:.2f} seconds")

# Expected output: Total time taken is ~1 second

The performance gain is dramatic. Instead of 5 seconds, the entire operation completes in just over 1 second—the time it takes for the longest single request to finish.

The Modern Paradigm: `asyncio` for Ultimate Scalability

`asyncio` uses cooperative multitasking. It runs on a single thread and relies on an event loop to manage tasks. Functions defined with `async def` are coroutines. When a coroutine encounters an `await` call (e.g., waiting for a network request), it explicitly yields control back to the event loop, which can then run another task. This avoids the overhead of creating, managing, and switching between OS-level threads, making `asyncio` potentially more scalable for applications with thousands of concurrent connections.

To use `asyncio` for HTTP requests, we need an async-compatible library like `aiohttp`.

import asyncio

import time

import aiohttp

# An async mock API function

async def fetch_stock_price_async(session, ticker):

print(f"Fetching price for {ticker}...")

# asyncio.sleep is the non-blocking equivalent of time.sleep

await asyncio.sleep(1)

price = 100 + hash(ticker) % 20

print(f"Finished fetching price for {ticker}")

return {"ticker": ticker, "price": price}

async def main():

tickers = ["AAPL", "GOOG", "MSFT", "AMZN", "TSLA"]

start_time = time.time()

async with aiohttp.ClientSession() as session:

tasks = [fetch_stock_price_async(session, ticker) for ticker in tickers]

results = await asyncio.gather(*tasks)

end_time = time.time()

print(f"\nAsyncio results: {results}")

print(f"Total time taken (Asyncio): {end_time - start_time:.2f} seconds")

# In a script, you would run the main coroutine

if __name__ == "__main__":

asyncio.run(main())

# Expected output: Total time taken is ~1 second

The performance is similar to `threading` for this small number of tasks, but the `asyncio` approach can scale to handle many more concurrent operations with less memory and CPU overhead due to its single-threaded, event-driven nature.

From Theory to Practice: A Concurrent Financial API Client

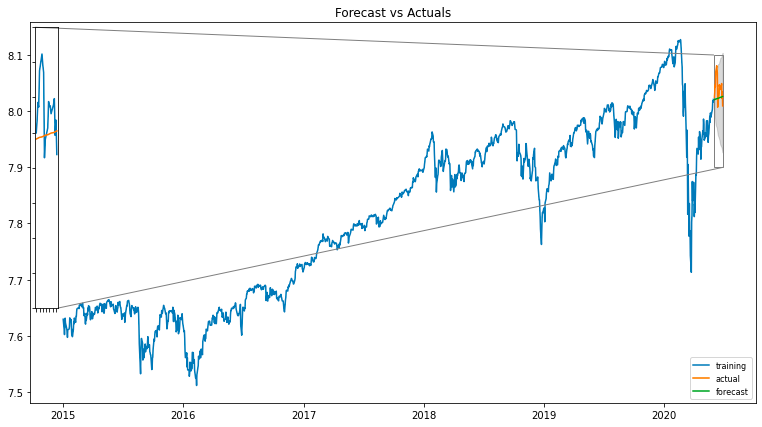

Let’s build a more realistic example that mimics a financial trading application. A common requirement is to fetch both historical market data for an asset and the current portfolio status before making a trading decision. These are two independent API calls that can be executed concurrently.

Designing a Concurrent `asyncio` Client

We’ll create an `APIBroker` class that uses `asyncio` and `aiohttp` to perform these actions simultaneously. This pattern is highly effective for building responsive dashboards or automated trading bots.

import asyncio

import time

import aiohttp

from random import random

class APIBroker:

def __init__(self, api_key):

self.api_key = api_key

self._session = aiohttp.ClientSession(headers={"Authorization": f"Bearer {self.api_key}"})

async def get_historical_data(self, ticker, period="1y"):

"""Simulates fetching historical price data for a ticker."""

print(f"Requesting historical data for {ticker}...")

# Simulate a longer network delay for larger data payload

await asyncio.sleep(1.5)

print(f"Received historical data for {ticker}.")

return {"ticker": ticker, "period": period, "data_points": 252}

async def get_portfolio_status(self):

"""Simulates fetching the current account and portfolio status."""

print("Requesting portfolio status...")

# Simulate a faster API call

await asyncio.sleep(0.5)

print("Received portfolio status.")

return {"cash": 10000.0, "positions": 5, "value": 54321.0}

async def get_trade_decision_data(self, ticker):

"""Runs required API calls concurrently to get data for a decision."""

print(f"--- Gathering data for {ticker} ---")

start_time = time.time()

# Create tasks for both API calls

task_history = asyncio.create_task(self.get_historical_data(ticker))

task_portfolio = asyncio.create_task(self.get_portfolio_status())

# Wait for both tasks to complete

historical_data, portfolio_status = await asyncio.gather(task_history, task_portfolio)

end_time = time.time()

print(f"--- Data gathered in {end_time - start_time:.2f} seconds ---")

return historical_data, portfolio_status

async def close(self):

await self._session.close()

async def run_scenario():

broker = APIBroker(api_key="your_secret_key")

# Sequentially, this would take 1.5s + 0.5s = 2.0s

# Concurrently, it will take max(1.5s, 0.5s) = 1.5s

hist_data, port_status = await broker.get_trade_decision_data("NVDA")

print("\n--- Final Data ---")

print(f"Historical Info: {hist_data}")

print(f"Portfolio Info: {port_status}")

await broker.close()

if __name__ == "__main__":

asyncio.run(run_scenario())

This example clearly demonstrates the power of `asyncio.gather`. The total time taken is dictated by the longest-running task (1.5 seconds), not the sum of all tasks (2.0 seconds). This 25% time saving on just two calls can translate into massive efficiency gains in a system making thousands of calls per minute.

Navigating the Concurrent Landscape: Best Practices and Pitfalls

While concurrency is powerful, it introduces complexity. Following best practices and being aware of common pitfalls is key to writing robust, maintainable concurrent code.

Best Practices for Concurrent Code

- Choose the Right Tool: Use `threading` when you need to integrate with blocking libraries or when the logic is simple. Opt for `asyncio` when building high-throughput network applications from the ground up, as it offers superior scalability for a very large number of connections.

- Manage Resources with Pools: Constantly opening and closing network connections is inefficient. Use session objects like `aiohttp.ClientSession` which manage an underlying connection pool for you, reusing connections to improve performance.

- Implement Rate Limiting: Hitting an API with thousands of requests per second is a quick way to get your IP address banned. Use mechanisms like `asyncio.Semaphore` to limit the number of concurrent requests to a level that respects the API’s rate limits.

- Ensure Graceful Shutdowns: Your application should handle interruptions (like `Ctrl+C`) gracefully. Implement signal handlers to cancel pending tasks and close resources like network sessions properly before exiting.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

- Blocking the Event Loop: The cardinal sin of `asyncio` is calling a standard blocking function (like `requests.get()` or `time.sleep()`) inside a coroutine. This will halt the entire event loop, freezing all other concurrent tasks. Always use the `async` versions of libraries (e.g., `aiohttp`, `asyncio.sleep`). If you must call blocking code, run it in a separate thread using `asyncio.to_thread()` (Python 3.9+) or `loop.run_in_executor()`.

- Ignoring Error Handling: When using `asyncio.gather`, if one of the tasks raises an exception, `gather` will propagate the exception immediately and cancel the remaining tasks. You might want to handle exceptions on a per-task basis. The `return_exceptions=True` argument in `gather` can be useful, as it will return exception objects in the results list instead of raising them.

- Race Conditions: While the GIL and `asyncio`’s single-threaded nature prevent many traditional race conditions, they can still occur if you are not careful with shared mutable state. A coroutine can yield control between reading and writing a shared variable, allowing another coroutine to modify it unexpectedly. Use synchronization primitives like `asyncio.Lock` when necessary.

Conclusion: Concurrency as a Core Competency

In the evolving world of software development, performance is not just a feature—it’s a fundamental requirement. As the latest python news and trends indicate, the language’s ecosystem is increasingly built around high-performance networking and data processing. For Python developers working with APIs, mastering concurrency is no longer optional; it is a core competency. By understanding the distinction between I/O-bound and CPU-bound tasks, you can make an informed decision between `threading` for simplicity and `asyncio` for ultimate scalability.

We’ve seen how transforming sequential, blocking API calls into a concurrent pattern can slash execution time, leading to faster, more responsive, and more efficient applications. Whether you are building a high-frequency trading bot, a real-time data analytics dashboard, or a large-scale web scraper, the principles and techniques discussed here provide a solid foundation for unlocking the true performance potential of Python in an I/O-driven world.