Python’s New Frontier: A Deep Dive into the Frameworks Revolutionizing Climate Science

The Unseen Force: How Python is Reshaping Climate Modeling

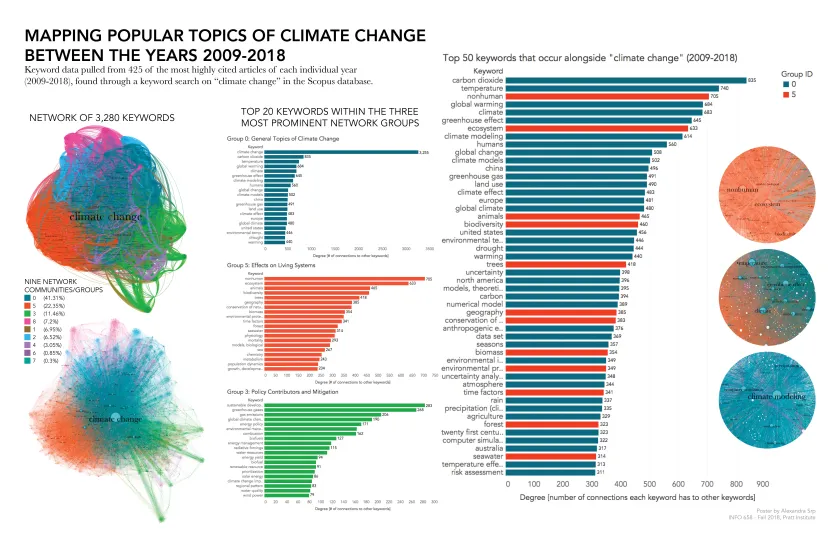

In the world of scientific computing, a quiet revolution is underway. For decades, complex domains like climate science have been dominated by legacy languages such as Fortran and C++, known for their raw performance but also for their steep learning curves and rigid structures. Today, the latest python news isn’t about web development or data analytics alone; it’s about Python’s ascendance as the lingua franca of scientific discovery. This shift is culminating in the development of new, accessible frameworks designed to democratize highly specialized fields. One of the most exciting frontiers for this transformation is global climate modeling, where new Python-based tools are making it possible for students, data scientists, and researchers to tackle some of the world’s most pressing questions with unprecedented ease and flexibility.

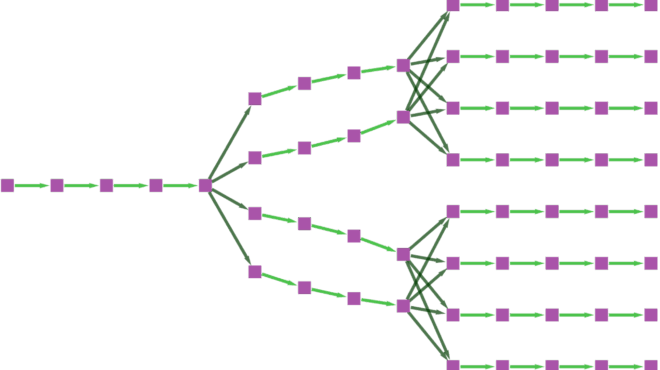

Traditionally, running a climate simulation required specialized hardware, arcane command-line interfaces, and a deep understanding of compiled languages. This created a significant barrier to entry, limiting participation to a small community of experts. Now, a new generation of Python frameworks is changing the paradigm. By leveraging Python’s rich scientific ecosystem—including libraries like NumPy, Xarray, and Dask—these tools offer a high-level, intuitive interface to complex climate dynamics. They are designed not just for large-scale research but also for education, enabling a more hands-on, interactive approach to learning about the intricate systems that govern our planet’s climate. This article explores the architecture, application, and impact of these groundbreaking Python frameworks.

Section 1: The Python Ecosystem and the Genesis of Modern Climate Tools

The rise of Python in scientific domains is not accidental. It’s the result of a mature, interconnected ecosystem of open-source libraries that provide the building blocks for sophisticated analysis and modeling. Understanding these foundational tools is key to appreciating why Python is the ideal language for the next generation of climate science frameworks.

Why Python is the Perfect Catalyst for Scientific Innovation

At the core of scientific Python is NumPy, which provides the fundamental `ndarray` object for efficient multi-dimensional array computation. Building on this, SciPy offers a vast collection of algorithms for optimization, integration, and signal processing. For data manipulation and analysis, Pandas introduced the DataFrame, a structure now ubiquitous in data science. However, for climate science, the most critical library is arguably Xarray.

Climate data is inherently multi-dimensional, often including latitude, longitude, altitude, and time. Xarray extends the power of NumPy arrays by adding labels (dimensions, coordinates, and attributes), making data selection, slicing, and computation far more intuitive and less error-prone. Instead of tracking array indices, a scientist can simply request data for a specific location and time range by name. This capability is a cornerstone of modern Python-based climate frameworks.

Consider loading a typical climate dataset, such as sea surface temperature, stored in a NetCDF file:

“`python

import xarray as xr

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Xarray makes loading complex, multi-dimensional data trivial

try:

# Assuming ‘sea_surface_temp.nc’ is a standard climate data file

ds = xr.open_dataset(‘sea_surface_temp.nc’)

print(ds)

# Select data for a specific time and plot the global temperature

sst_jan_2023 = ds[‘sst’].sel(time=’2023-01-15′, method=’nearest’)

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 6))

sst_jan_2023.plot(cmap=’viridis’)

plt.title(‘Global Sea Surface Temperature – January 2023’)

plt.xlabel(‘Longitude’)

plt.ylabel(‘Latitude’)

plt.grid(True)

plt.show()

except FileNotFoundError:

print(“Sample data file ‘sea_surface_temp.nc’ not found. This is a demonstrative example.”)

except Exception as e:

print(f”An error occurred: {e}”)

“`

This snippet demonstrates the power of the ecosystem. Xarray handles the file I/O and provides a labeled data structure, while Matplotlib provides immediate visualization. This seamless integration is what new frameworks leverage to build more complex abstractions.

Earth satellite data analytics – Korean startups join push to champion satellite data analytics …

The Gap These New Frameworks Fill

Despite this powerful ecosystem, a gap remained between data analysis and dynamic modeling. Existing General Circulation Models (GCMs) were monolithic, written in Fortran, and difficult to modify. A researcher wanting to test a new cloud parameterization scheme would need to dive into thousands of lines of legacy code. An educator couldn’t easily create a simplified model to demonstrate the greenhouse effect. The new wave of Python frameworks aims to fill this gap by providing a modular, extensible, and “Pythonic” API for climate dynamics itself.

Section 2: A Technical Anatomy of a Python-Based Climate Framework

To understand how these frameworks function, let’s conceptualize a hypothetical framework we’ll call `ClimaPy`. It is designed with modularity and ease of use at its core, abstracting away the low-level mathematics to expose a clean, high-level interface.

Core Architectural Components

A framework like `ClimaPy` would likely be built around several key components:

Grid Manager: A module for defining the spatial and temporal domains of the simulation. This could handle different projections (e.g., latitude-longitude, polar stereographic) and resolutions.

State Variables: A core class to manage the model’s state, such as temperature, pressure, and wind vectors, likely built on top of an Xarray `Dataset`.

Dynamical Core: The engine that solves the primitive equations of atmospheric or oceanic motion. While the interface is Python, the performance-critical code here might be JIT-compiled with Numba or written in C/Fortran and wrapped with Cython.

Physics Modules: Pluggable components that represent physical processes too small or complex to be resolved by the dynamical core, such as radiation, convection, and cloud formation. This is where extensibility is key.

I/O and Diagnostics: Tools for saving model output to standard formats like NetCDF and for calculating diagnostic variables on the fly.

Practical Example: A Simplified Energy Balance Model

Let’s demonstrate how `ClimaPy` might be used to build a simple one-dimensional Energy Balance Model (EBM), a fundamental tool in climate education. This model simulates the average temperature at different latitudes based on incoming solar radiation and outgoing thermal radiation.

“`python

import numpy as np

import xarray as xr

# — Hypothetical ClimaPy Framework Classes —

class EBMPhysics:

“””A simplified physics module for an Energy Balance Model.”””

def __init__(self, solar_constant=1367, albedo=0.3, emissivity=0.61):

self.S0 = solar_constant # W/m^2

self.alpha = albedo # Planetary albedo (reflectivity)

self.epsilon = emissivity # Effective emissivity of the atmosphere

self.sigma = 5.67e-8 # Stefan-Boltzmann constant

def step(self, state):

“””Calculates the temperature change for one time step.”””

lat = state[‘lat’]

temp = state[‘temperature’]

# Incoming solar radiation (depends on latitude)

insolation = self.S0 / 4 * (1 – self.alpha) * (1 – 0.48 * (3 * np.sin(np.deg2rad(lat))**2 – 1) / 2)

# Outgoing longwave radiation

outgoing_radiation = self.epsilon * self.sigma * (temp**4)

# Net radiation balance

net_radiation = insolation – outgoing_radiation

# For simplicity, assume a heat capacity and calculate dT

# A real model would include heat transport

heat_capacity = 2e7 # J/m^2/K

dT = net_radiation / heat_capacity * (3600 * 24) # Temp change per day

return dT

class ClimateModel:

“””A simple model runner.”””

def __init__(self, physics_module, initial_state):

self.physics = physics_module

self.state = initial_state

self.history = [initial_state.copy(deep=True)]

def run(self, steps):

“””Run the simulation for a number of steps.”””

for i in range(steps):

# Calculate the change in state

delta_state = self.physics.step(self.state)

# Update the state (Euler forward step)

self.state[‘temperature’] += delta_state

# Save history

self.history.append(self.state.copy(deep=True))

print(f”Step {i+1}/{steps} – Mean Temp: {self.state[‘temperature’].mean().item():.2f} K”)

return xr.concat(self.history, dim=’time’)

# — Using the Framework —

# 1. Define the model grid and initial state using Xarray

latitudes = np.arange(-90, 91, 10)

initial_temp = np.full_like(latitudes, 288.0) # Initial temp of 288K (15°C) everywhere

initial_state = xr.Dataset(

{

“temperature”: ((“lat”,), initial_temp)

},

coords={“lat”: latitudes, “time”: 0}

)

initial_state.lat.attrs[‘units’] = ‘degrees_north’

initial_state.temperature.attrs[‘units’] = ‘K’

# 2. Instantiate the physics and the model

ebm_physics = EBMPhysics()

model = ClimateModel(physics_module=ebm_physics, initial_state=initial_state)

# 3. Run the simulation

print(“Starting a simplified Energy Balance Model simulation…”)

results = model.run(steps=100) # Run for 100 daily time steps

# 4. Analyze and plot the final state

final_temperature = results.isel(time=-1)[‘temperature’]

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

final_temperature.plot(label=’Final Temperature’)

plt.title(‘Simulated Zonal Mean Temperature Profile’)

plt.xlabel(‘Latitude’)

plt.ylabel(‘Temperature (K)’)

plt.grid(True)

plt.legend()

plt.show()

“`

This example, while simplified, illustrates the core philosophy: the scientist defines the initial conditions and the physics, and the framework handles the simulation loop and data management. The use of Xarray for the model state makes the data self-describing and easy to analyze.

Section 3: Bridging Education, Research, and Reproducibility

The primary impact of these Python frameworks extends beyond just writing code. They are fundamentally changing how climate science is taught, how research is conducted, and how results are shared.

Earth satellite data analytics – Quant Data & Analytics to Leverage Satellogic Imagery in Saudi …

Empowering the Next Generation of Scientists

In an educational setting, a Python-based framework transforms abstract concepts into interactive experiments. A student can take the Energy Balance Model above, create a subclass of `EBMPhysics` to add an ice-albedo feedback mechanism, and immediately see the impact on global temperatures. This hands-on approach fosters a much deeper intuition for climate dynamics than textbooks alone ever could. It lowers the barrier to entry, inviting students from computer science, physics, and environmental science to engage with climate modeling without needing to first master Fortran.

Accelerating Research and Fostering Collaboration

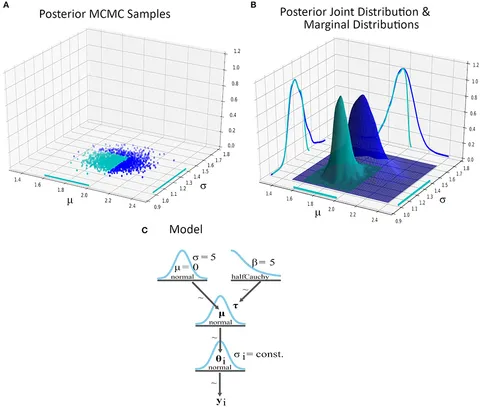

For researchers, the main benefit is speed of iteration. Instead of spending weeks implementing a new idea in a complex legacy model, they can prototype it in Python in a matter of hours. This “fail fast” approach accelerates discovery. Furthermore, because the entire toolchain is open-source and based on a widely known language, collaboration becomes seamless. A researcher in one institution can easily share a Jupyter Notebook with a colleague across the globe, who can then run, verify, and build upon the work. This leads to more transparent and reproducible science—a critical need in a field with such significant societal implications. The latest python news in the scientific community often highlights these collaborative successes.

Section 4: Best Practices, Performance, and Future Directions

While Python offers immense benefits in terms of accessibility and flexibility, it’s crucial to address the elephant in the room: performance. We must also consider best practices for using these powerful new tools effectively.

The Performance vs. Accessibility Trade-off

Earth satellite data analytics – Satellite Data Analytics And Imagery Analysis By EOSDA

Python is an interpreted language and is inherently slower than compiled languages like Fortran for raw numerical computation. A naive Python implementation of a GCM would be too slow to be practical. However, modern Python frameworks overcome this limitation in several ways:

Leveraging Compiled Backends: Most core computations rely on NumPy, which is a Python wrapper around highly optimized C and Fortran libraries. The heavy lifting is not done in Python.

Just-In-Time (JIT) Compilation: Libraries like Numba can compile Python code to machine code at runtime. By adding a simple decorator (`@numba.jit`) to a computationally intensive function, developers can achieve C-like speeds without leaving the Python environment.

Parallelization with Dask: For handling datasets that are too large to fit in memory, Dask provides parallel computing capabilities. Dask integrates seamlessly with Xarray, allowing scientists to perform complex analyses on massive climate datasets distributed across a cluster of machines.

Recommendations for Effective Use

To make the most of these frameworks, users should adopt several best practices:

Use Virtual Environments: Always use a tool like `venv` or `conda` to manage project dependencies. This prevents conflicts and ensures reproducibility.

Embrace Version Control: Use Git to track changes to your models, scripts, and notebooks. This is essential for collaborative work and for keeping a record of your experiments.

Write Modular and Reusable Code: Even though the framework provides a high-level API, structure your own code logically. Write functions and classes for specific tasks, such as data preprocessing or visualization, to make your analysis easier to understand and reuse.

Contribute to the Community: These frameworks are open-source. If you find a bug or develop a useful new physics module, consider contributing it back to the project. This collective effort is what drives innovation.

Conclusion: A New Climate for Scientific Discovery

The emergence of powerful, user-friendly Python frameworks for climate modeling represents a paradigm shift in the field. By abstracting away complexity and leveraging Python’s world-class scientific ecosystem, these tools are demolishing the barriers that once limited access to climate science. They empower students to learn by doing, enable researchers to innovate more rapidly, and foster a culture of open, transparent, and reproducible science. While challenges like performance optimization remain, the combination of JIT compilation, parallel computing, and community-driven development has proven to be a formidable solution.

The most exciting python news today is not just about a new library feature; it’s about how the language and its community are empowering experts and newcomers alike to tackle some of humanity’s greatest challenges. As these frameworks mature, they will undoubtedly become an indispensable part of the toolkit for understanding and protecting our planet, ushering in a new, more collaborative, and more insightful era of climate science.