Advanced Python Async Programming Techniques – Part 3

Welcome back to our comprehensive series on asynchronous programming in Python. In the previous installments, we laid the groundwork by exploring the fundamentals of coroutines, the event loop, and basic concurrent execution with asyncio.gather(). Now, it’s time to elevate your skills. This guide delves into the advanced patterns and techniques essential for building robust, scalable, and production-ready asynchronous applications. We will move beyond simple concurrent tasks to tackle complex challenges like resource management, sophisticated task coordination, and the graceful integration of blocking code. Mastering these concepts will unlock the full potential of Python’s asyncio library, enabling you to write highly efficient, I/O-bound applications that can handle massive concurrency with ease.

Understanding the Need for Advanced Async Patterns

While basic async/await syntax is straightforward, real-world applications present complexities that require more sophisticated tools. When you have hundreds or thousands of coroutines running concurrently, you can no longer treat them as a simple “fire-and-forget” collection. You need mechanisms to control access to shared resources, manage task lifecycles with precision, and prevent the entire system from grinding to a halt due to a single misbehaving component. This is where advanced patterns become indispensable.

Why Synchronization is Crucial in Async

You might think that since asyncio runs on a single thread, you’re safe from the classic race conditions found in multi-threaded programming. This is only partially true. While you won’t have two lines of Python code executing at the exact same microsecond, a coroutine can be suspended at any await point. If another coroutine resumes and modifies a shared state before the first one continues, you can still end up with inconsistent data. Consider an application managing a limited pool of API connections. If multiple coroutines try to grab a connection simultaneously, you need a way to ensure only a set number of connections are active at once to avoid being rate-limited or banned. This is where async synchronization primitives come into play.

Beyond asyncio.gather(): Sophisticated Task Orchestration

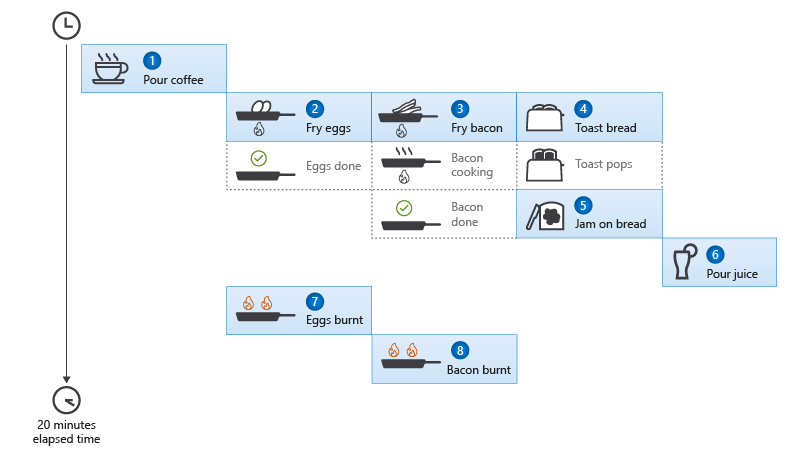

asyncio.gather() is a powerful tool for running a list of awaitables concurrently and waiting for all of them to complete. However, it has limitations. What if you need to process results as they arrive, rather than waiting for the slowest task to finish? What if you want to stop all other tasks as soon as one of them finds a valid result? Or what if you need to impose a strict timeout on a group of operations? These scenarios require more advanced task management functions like asyncio.as_completed() and asyncio.wait(), which provide finer-grained control over how and when you interact with your concurrent tasks.

Mastering Concurrency Control with Synchronization Primitives

The asyncio library provides a set of synchronization primitives modeled after those in the traditional threading module, but adapted for use with coroutines. Using them correctly is key to building stable applications.

Limiting Concurrency with asyncio.Semaphore

A semaphore is a counter that controls access to a finite resource. It’s one of the most practical primitives for tasks like web scraping or interacting with third-party APIs that have rate limits. A semaphore is initialized with a value representing the number of available “slots.” Each time a coroutine wants to access the resource, it must first `acquire()` the semaphore, which decrements the counter. If the counter is zero, the coroutine will wait until another coroutine `release()`s the semaphore, incrementing the counter.

Let’s see a practical example of using a semaphore to limit concurrent requests to a web server:

import asyncio

import aiohttp

async def fetch_url(session, url, semaphore):

# The async with statement ensures the semaphore is released

# even if an exception occurs.

async with semaphore:

print(f"Fetching {url}...")

try:

async with session.get(url) as response:

await response.text()

print(f"Finished fetching {url}")

return url, "Success"

except Exception as e:

print(f"Failed to fetch {url}: {e}")

return url, "Failed"

async def main():

# Limit to 5 concurrent requests

semaphore = asyncio.Semaphore(5)

urls = [f"http://example.com/{i}" for i in range(20)]

async with aiohttp.ClientSession() as session:

tasks = [fetch_url(session, url, semaphore) for url in urls]

results = await asyncio.gather(*tasks)

print("All fetches complete.")

if __name__ == "__main__":

asyncio.run(main())

In this code, even though we create 20 tasks at once, the asyncio.Semaphore(5) ensures that no more than five fetch_url coroutines are actively making network requests at any given time. The others will pause at the async with semaphore: line until a slot becomes free.

Protecting Shared State with asyncio.Lock

A Lock is the simplest synchronization primitive. It provides exclusive access to a resource. Only one coroutine can hold the lock at a time. This is useful for protecting critical sections of code that modify a shared state, preventing data corruption.

import asyncio

class SharedCounter:

def __init__(self):

self._value = 0

self._lock = asyncio.Lock()

async def increment(self):

async with self._lock:

# This section is protected. Only one coroutine can be here at a time.

current_value = self._value

await asyncio.sleep(0.01) # Simulate some I/O work

self._value = current_value + 1

async def worker(counter):

for _ in range(100):

await counter.increment()

async def main():

counter = SharedCounter()

tasks = [worker(counter) for _ in range(10)]

await asyncio.gather(*tasks)

print(f"Final counter value: {counter._value}")

if __name__ == "__main__":

asyncio.run(main()) # Correctly prints 1000

Without the lock, multiple coroutines could read self._value, then get suspended at the await, and all resume later with the same stale value, leading to a final count much lower than 1000. The lock guarantees that the read-modify-write operation is atomic.

Advanced Task Management and Exception Handling

Properly managing the lifecycle of your tasks—including timeouts, cancellations, and error propagation—is a hallmark of a professional-grade async application. Keeping up with the latest **python news** and library updates is key, as new features like the asyncio.timeout() context manager in Python 3.11 simplify timeout handling significantly.

Processing Results on Arrival with asyncio.as_completed()

Unlike asyncio.gather(), which returns all results at the end, asyncio.as_completed() provides an iterator that yields futures as they complete. This is incredibly useful when you want to start processing data from faster tasks while slower ones are still running.

import asyncio

import random

async def long_running_task(name, delay):

print(f"Task {name} starting, will take {delay:.2f} seconds.")

await asyncio.sleep(delay)

print(f"Task {name} finished.")

return f"Result from {name}"

async def main():

tasks = [long_running_task(f"Task-{i}", random.uniform(0.5, 3.0)) for i in range(5)]

print("Starting tasks...")

for future in asyncio.as_completed(tasks):

result = await future

print(f"Received result: '{result}'")

if __name__ == "__main__":

asyncio.run(main())

When you run this code, you will see results being printed as soon as each task finishes, not all at once at the very end. This pattern is ideal for improving responsiveness in applications that perform many independent I/O operations.

Handling Timeouts and Cancellations

An I/O operation might hang indefinitely. A robust application must be able to time out and move on. The modern way (Python 3.11+) to handle this is with the asyncio.timeout() context manager.

import asyncio

async def slow_operation():

print("Slow operation started...")

await asyncio.sleep(10) # This will never finish in time

print("Slow operation finished.")

async def main():

try:

# This operation must complete within 2 seconds

async with asyncio.timeout(2):

await slow_operation()

except TimeoutError:

print("The operation timed out!")

if __name__ == "__main__":

asyncio.run(main())

When the timeout is reached, a TimeoutError is raised inside the coroutine, which you can catch and handle. This is much cleaner than the older asyncio.wait_for() function. Cancellation is a related concept where a task is explicitly told to stop. When a task is cancelled, an asyncio.CancelledError is raised at the next await point. Well-written coroutines should catch this error to perform necessary cleanup (like closing file handles or database connections) before re-raising the exception.

Bridging the Gap: Integrating Synchronous and Asynchronous Code

One of the biggest challenges developers face is integrating asyncio into existing projects that use blocking libraries (e.g., standard database drivers, file I/O, or CPU-intensive libraries like Pillow or NumPy). Calling a blocking function directly from a coroutine is a critical error because it will block the entire event loop, freezing your application.

The Solution: loop.run_in_executor()

The correct way to handle blocking code is to run it in a separate thread pool using loop.run_in_executor(). This method takes an executor (typically a ThreadPoolExecutor) and a regular, blocking function. It schedules the function to run in one of the executor’s threads and returns an awaitable future. This allows the event loop to continue running other coroutines while the blocking call executes in the background.

import asyncio

import time

from concurrent.futures import ThreadPoolExecutor

def blocking_io_call(duration):

"""A function that simulates a blocking I/O operation."""

print(f"Blocking call started, will take {duration}s.")

time.sleep(duration) # NEVER use time.sleep in a coroutine!

print("Blocking call finished.")

return "Blocking data"

async def main():

loop = asyncio.get_running_loop()

print("Scheduling blocking call...")

# By default, asyncio uses a default ThreadPoolExecutor.

# We can pass None to use it.

future = loop.run_in_executor(

None, blocking_io_call, 3

)

# Do other async work while the blocking call runs

for i in range(5):

print(f"Async work happening... {i+1}/5")

await asyncio.sleep(0.5)

print("Waiting for blocking call to complete...")

result = await future

print(f"Result from blocking call: {result}")

if __name__ == "__main__":

asyncio.run(main())

In this example, the async “heartbeat” prints continue to run while the 3-second `blocking_io_call` executes in another thread. This pattern is the essential bridge for using the vast ecosystem of synchronous Python libraries within a modern asyncio application.

Conclusion: Building Production-Ready Async Applications

We have journeyed from the basics into the heart of advanced asynchronous programming in Python. By mastering synchronization primitives like Semaphore and Lock, you can safely manage shared resources and prevent race conditions. By leveraging sophisticated task management tools like asyncio.as_completed() and robust timeout mechanisms, you gain fine-grained control over task execution and application responsiveness. Finally, by understanding how to properly integrate blocking code with run_in_executor(), you can build powerful hybrid applications that get the best of both the synchronous and asynchronous worlds. These advanced techniques are not just theoretical; they are the practical, everyday tools required to build resilient, high-performance, and scalable network applications with Python’s asyncio.