Python Microservices Architecture Guide – Part 3

Welcome to the third installment of our comprehensive guide to building robust microservices architecture using Python. In the previous parts, we laid the groundwork, transitioning from monolithic designs to a distributed ecosystem. Now, we venture into the heart of microservices implementation, tackling the advanced challenges that define the success and resilience of a distributed system. This article dives deep into the critical pillars of service communication, data consistency, comprehensive monitoring, and sophisticated deployment strategies. Mastering these concepts is essential for any developer or architect aiming to build scalable, fault-tolerant, and maintainable Python applications in a microservices world. We’ll move beyond theory, providing practical insights, best practices, and tangible code examples to illuminate the path forward. The latest python news consistently highlights the growing need for these advanced skills as more companies adopt this architectural style.

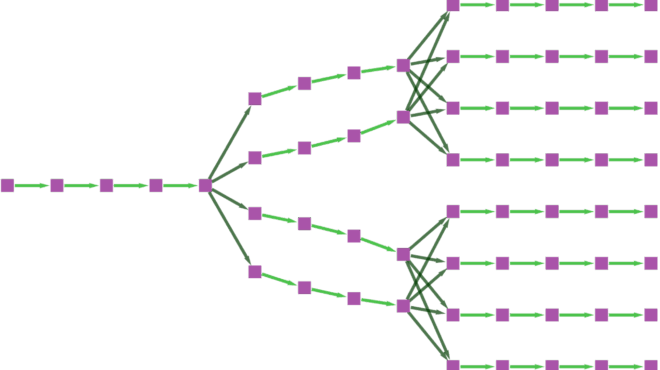

Advanced Service-to-Service Communication Patterns

In a microservices architecture, services must communicate with each other effectively. The choice of communication pattern has profound implications for system performance, resilience, and complexity. Simply defaulting to REST APIs for everything can lead to tightly coupled, brittle systems. A mature architecture employs a mix of synchronous and asynchronous patterns tailored to specific use cases.

Synchronous vs. Asynchronous Communication

Synchronous communication, typically implemented using HTTP/REST or gRPC, is a blocking pattern. The client sends a request and waits for a response from the server. This is simple to understand and implement, making it ideal for request/response workflows like a user fetching their profile data. However, its major drawback is temporal coupling; if the downstream service is slow or unavailable, the calling service is blocked, potentially causing cascading failures throughout the system. A “new” service failing can bring down others that depend on it.

Asynchronous communication decouples services. The client sends a message to a message broker (like RabbitMQ, Apache Kafka, or AWS SQS) and doesn’t wait for an immediate response. The receiving service processes the message when it’s ready. This pattern is perfect for long-running tasks, notifications, or workflows where an immediate response isn’t necessary. It enhances system resilience, as the message broker can queue messages even if the consumer service is temporarily down. The key trade-off is increased complexity in implementation and reasoning about the system’s state.

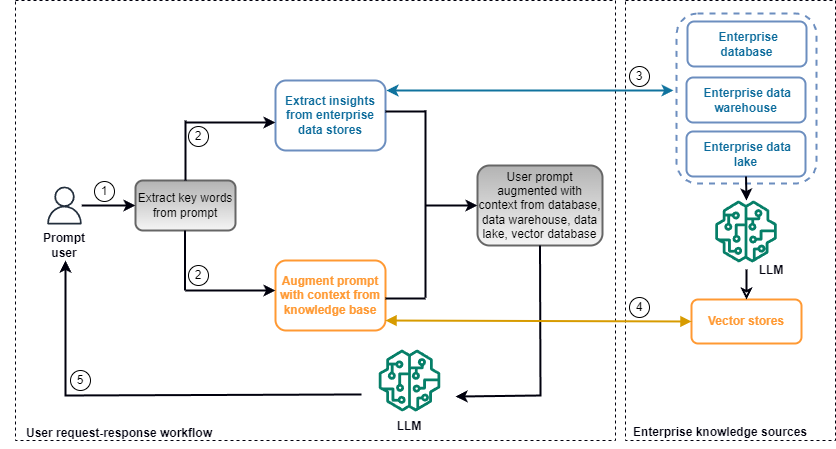

The API Gateway: A Unified Entry Point

Exposing every microservice directly to the public internet is a security and management nightmare. The API Gateway pattern solves this by providing a single, unified entry point for all external clients. It acts as a reverse proxy, routing incoming requests to the appropriate downstream service. Beyond simple routing, an API Gateway can handle cross-cutting concerns such as:

- Authentication and Authorization: Validating credentials or JWTs before forwarding requests.

- Rate Limiting and Throttling: Protecting services from being overwhelmed by too many requests.

- Request Aggregation: Combining results from multiple microservices into a single response, simplifying the client-side logic.

- Protocol Translation: Allowing clients to use a standard protocol like REST while internal services might use gRPC or another protocol.

Here is a conceptual example of a simple API Gateway using FastAPI in Python that routes requests to an “Order Service” and a “User Service”:

# api_gateway.py

import httpx

from fastapi import FastAPI, Request, Response

app = FastAPI()

# Service locations could be loaded from a config or service discovery

SERVICE_URLS = {

"users": "http://localhost:8001",

"orders": "http://localhost:8002",

}

@app.api_route("/{service}/{path:path}", methods=["GET", "POST", "PUT", "DELETE"])

async def route_request(service: str, path: str, request: Request):

"""

A simple routing function that forwards requests.

This is a basic implementation; a real one would handle auth, etc.

"""

if service not in SERVICE_URLS:

return Response(content="Service not found", status_code=404)

service_url = f"{SERVICE_URLS[service]}/{path}"

async with httpx.AsyncClient() as client:

# Forward the request with headers, query params, and body

response = await client.request(

method=request.method,

url=service_url,

headers=request.headers,

params=request.query_params,

content=await request.body()

)

# Return the response from the downstream service

return Response(

content=response.content,

status_code=response.status_code,

headers=response.headers

)

Tackling Data Consistency in a Distributed World

One of the most significant challenges in microservices is maintaining data consistency across multiple services, each with its own private database. Traditional ACID transactions, which rely on two-phase commits, are often impractical in a distributed environment due to performance bottlenecks and reduced availability. Instead, microservice architectures embrace the concept of eventual consistency.

Understanding the Saga Pattern

The Saga pattern is a design pattern for managing data consistency across microservices in the absence of distributed transactions. A saga is a sequence of local transactions. Each local transaction updates the database within a single service and publishes an event or message that triggers the next local transaction in the next service. If a local transaction fails, the saga executes a series of compensating transactions to undo the preceding transactions, thereby restoring data consistency.

There are two primary ways to coordinate a saga:

- Choreography: In this event-driven approach, services communicate by publishing and subscribing to events. There is no central coordinator. For example, an

OrderServicecreates an order and publishes anOrderCreatedevent. APaymentServicelistens for this event, processes the payment, and publishes aPaymentProcessedevent. This is decentralized and simple for short sagas but can become difficult to track and debug as the number of services grows. - Orchestration: This approach uses a central coordinator (the “orchestrator”) to tell the participating services what to do. The orchestrator, which can be a dedicated service, manages the entire sequence of transactions. It sends commands to each service and waits for a reply before proceeding to the next step. If a step fails, the orchestrator is responsible for triggering the necessary compensating transactions. This approach is easier to monitor and manage for complex sagas but introduces a potential single point of failure and a risk of tight coupling to the orchestrator.

Implementing Sagas with Message Queues

Message queues are a natural fit for implementing choreographed sagas. Let’s consider an e-commerce order flow using RabbitMQ with the Python library pika.

Order Service (Producer):

# order_service.py

import pika

import json

def create_order(order_details):

# 1. Save order to local database with "PENDING" status

print("Order created in DB, status: PENDING")

# 2. Publish an OrderCreated event

connection = pika.BlockingConnection(pika.ConnectionParameters('localhost'))

channel = connection.channel()

channel.exchange_declare(exchange='order_events', exchange_type='fanout')

message = json.dumps({"order_id": order_details["id"], "amount": order_details["price"]})

channel.basic_publish(exchange='order_events', routing_key='', body=message)

print(f" [x] Sent {message}")

connection.close()

# Example usage

create_order({"id": 123, "price": 99.99})

The PaymentService and InventoryService would then subscribe to the order_events exchange, process the message, and publish their own events (e.g., PaymentSuccessful or InventoryDecremented) to continue the saga.

Achieving Observability: Monitoring, Logging, and Tracing

In a monolithic application, debugging is relatively straightforward. In a distributed system with dozens of services, understanding system behavior and diagnosing problems is impossible without a robust observability strategy. Observability is often described by its three pillars: logs, metrics, and traces.

The Three Pillars of Observability

- Logging: Logs are discrete, timestamped events that provide context about what happened at a specific point in time. In a microservices environment, it’s crucial to centralize logs from all services into a single, searchable platform like the ELK Stack (Elasticsearch, Logstash, Kibana) or Splunk. Python’s built-in

loggingmodule can be configured to output logs in a structured format (like JSON) to make them easily parsable. - Metrics: Metrics are numerical representations of data measured over time, such as CPU usage, memory consumption, request latency, or error rates. They are excellent for monitoring overall system health and setting up alerts. The de facto standard for collecting metrics in a cloud-native environment is Prometheus, an open-source monitoring system, often paired with Grafana for visualization.

- Distributed Tracing: Tracing allows you to follow the entire lifecycle of a request as it travels through multiple microservices. Each service adds contextual information (a “span”) to a shared trace, allowing you to visualize the complete call graph, identify performance bottlenecks, and pinpoint the source of errors. Popular open-source tools for distributed tracing include Jaeger and Zipkin, which adhere to the OpenTelemetry standard.

Practical Implementation with Python

Integrating observability tools into your Python services is easier than ever. Libraries like prometheus-client allow you to expose a /metrics endpoint for Prometheus to scrape, while OpenTelemetry provides a standardized way to instrument your code for tracing and metrics collection across various frameworks like Flask, FastAPI, and Django.

Sophisticated Deployment and Operational Strategies

Deploying a single monolithic application is a well-understood process. Deploying and managing a fleet of microservices requires a completely different set of tools and strategies focused on automation, containerization, and orchestration.

Containerization with Docker and Orchestration with Kubernetes

Docker has become the standard for packaging microservices. It allows you to bundle your Python application, its dependencies, and its configuration into a lightweight, portable container. This ensures that the service runs consistently across all environments, from a developer’s laptop to a production server. A `Dockerfile` defines the steps to build this container image.

While Docker is great for running one container, Kubernetes (K8s) is the leading platform for managing thousands of containers at scale. It’s a container orchestrator that automates the deployment, scaling, and self-healing of your microservices. Kubernetes handles complex tasks like:

- Service Discovery and Load Balancing: Automatically routing traffic to healthy instances of a service.

- Automated Rollouts and Rollbacks: Deploying new versions of a service with zero downtime and automatically rolling back if something goes wrong.

- Self-Healing: Restarting failed containers and rescheduling them on healthy nodes.

CI/CD Pipelines and Advanced Deployment Patterns

A robust Continuous Integration/Continuous Deployment (CI/CD) pipeline is non-negotiable for microservices. Each service should have its own automated pipeline that builds the Docker image, runs a suite of tests (unit, integration, contract), and deploys the service to a staging or production environment. Tools like Jenkins, GitLab CI, and GitHub Actions are commonly used to build these pipelines.

To minimize risk during production deployments, teams often use advanced patterns:

- Blue-Green Deployment: Two identical production environments, “Blue” and “Green,” are maintained. If Blue is live, the new version is deployed to Green. After testing, traffic is switched from Blue to Green. This allows for instant rollback by simply switching traffic back to Blue.

- Canary Release: The new version of a service is gradually rolled out to a small subset of users. The team monitors performance and error rates. If everything looks good, the rollout is expanded until 100% of users are on the new version. This limits the impact of a potential bug.

Conclusion: Embracing the Complexity for Greater Scalability

Navigating the advanced landscape of Python microservices architecture requires moving beyond basic service creation and tackling the inherent complexities of distributed systems. We’ve explored the critical strategies for managing service communication with patterns like the API Gateway, ensuring data consistency with the Saga pattern, and achieving system-wide visibility through the three pillars of observability. Furthermore, we’ve seen how modern operational practices, centered on Docker, Kubernetes, and CI/CD, are essential for deploying and managing these systems effectively. While the learning curve is steep, the payoff is immense: a highly scalable, resilient, and adaptable system that can evolve with your business needs. By thoughtfully applying these advanced techniques, your Python microservices will be robust, maintainable, and ready for production at scale. The journey is complex, but the architectural freedom and power it provides are well worth the investment.