Python Microservices Architecture Guide – Part 5

Welcome to the fifth installment of our comprehensive guide on building robust microservices architecture using Python. In the previous parts, we laid the groundwork, exploring the fundamental principles, setting up basic services, and discussing containerization. Now, we venture into the advanced territory that separates a functional prototype from a resilient, production-grade distributed system. This article delves deep into the critical pillars of a mature microservices ecosystem: sophisticated service communication, strategies for maintaining data consistency, achieving true observability, and implementing advanced deployment patterns.

As applications scale, the complexities of managing dozens or even hundreds of services become apparent. Simple REST calls are no longer sufficient, data integrity across service boundaries becomes a major challenge, and understanding system behavior requires more than just checking log files. Here, we will tackle these challenges head-on. We will explore high-performance communication with gRPC, manage distributed transactions with the Saga pattern, and transform our monitoring approach into a full-fledged observability strategy using modern tools. Mastering these advanced techniques is essential for any developer or architect aiming to leverage the full power of Python in a distributed environment, ensuring your applications are not only scalable but also reliable and maintainable in the long run.

Advanced Service Communication: The Nervous System of Your Architecture

Effective communication is the lifeblood of any microservices architecture. While simple RESTful APIs are a great starting point, mature systems often require more specialized and efficient communication patterns to handle diverse workloads. Choosing the right pattern is crucial for performance, resilience, and loose coupling between your services.

Synchronous Communication: When You Need an Immediate Answer

Synchronous communication is a blocking pattern where the client sends a request and waits for a response from the server. It’s straightforward and familiar, making it ideal for query-based operations where the user is actively waiting for data.

REST APIs with FastAPI

REST remains the de facto standard for many public-facing and internal APIs due to its simplicity and reliance on standard HTTP methods. Python frameworks like FastAPI have made building high-performance, self-documenting REST APIs easier than ever. Its use of Pydantic for data validation and Starlette for asynchronous performance makes it a top choice.

High-Performance with gRPC

For internal, service-to-service communication where performance is paramount, gRPC (gRPC Remote Procedure Calls) offers a significant advantage. Developed by Google, it uses HTTP/2 for transport and Protocol Buffers as its interface definition language.

- Performance: gRPC is significantly faster than REST because it serializes data into a compact binary format and leverages the multiplexing capabilities of HTTP/2.

- Type Safety: By defining your service contracts in

.protofiles, you generate client and server code, ensuring that data structures are consistent across services and reducing runtime errors. - Streaming: gRPC natively supports bidirectional streaming, allowing for more complex and efficient communication patterns, such as real-time data feeds or large file transfers.

Here’s a glimpse of a Python gRPC server definition:

# user_service.py

import grpc

from concurrent import futures

import user_pb2

import user_pb2_grpc

class UserService(user_pb2_grpc.UserServicer):

def GetUser(self, request, context):

# In a real app, you'd fetch this from a database

if request.user_id == "123":

return user_pb2.UserResponse(name="Alice", email="alice@example.com")

else:

context.set_code(grpc.StatusCode.NOT_FOUND)

context.set_details("User not found")

return user_pb2.UserResponse()

def serve():

server = grpc.server(futures.ThreadPoolExecutor(max_workers=10))

user_pb2_grpc.add_UserServicer_to_server(UserService(), server)

server.add_insecure_port('[::]:50051')

server.start()

server.wait_for_termination()

if __name__ == '__main__':

serve()

Asynchronous Communication: Decoupling for Resilience and Scale

Asynchronous communication is non-blocking. A service sends a message or event and doesn’t wait for an immediate response. This decouples services, meaning the sender doesn’t need to know about the consumer, and the consumer doesn’t need to be available when the message is sent. This pattern is fundamental to building resilient and scalable systems.

Message Queues and Event-Driven Architecture

Using a message broker like RabbitMQ or Apache Kafka is the most common way to implement asynchronous communication. Services publish events (e.g., OrderCreated, PaymentProcessed) to a central broker, and other interested services subscribe to these events to perform their tasks. This event-driven approach allows for incredible flexibility. If you need a new service to react to an order being created, you simply have it subscribe to the OrderCreated event—no changes are needed in the original Order Service.

Using the pika library for RabbitMQ in Python:

# payment_service.py (Publisher)

import pika

import json

connection = pika.BlockingConnection(pika.ConnectionParameters('localhost'))

channel = connection.channel()

channel.queue_declare(queue='order_created')

order_details = {'order_id': 'xyz-789', 'amount': 99.99}

channel.basic_publish(exchange='',

routing_key='order_created',

body=json.dumps(order_details))

print(" [x] Sent 'Order Created' event")

connection.close()

Ensuring Data Consistency in a Distributed World

One of the most significant challenges in microservices is maintaining data consistency across multiple services, each with its own database. Traditional ACID transactions that work beautifully in a monolith are not practical in a distributed environment. Instead, we must embrace the concept of eventual consistency and use patterns designed for distributed systems.

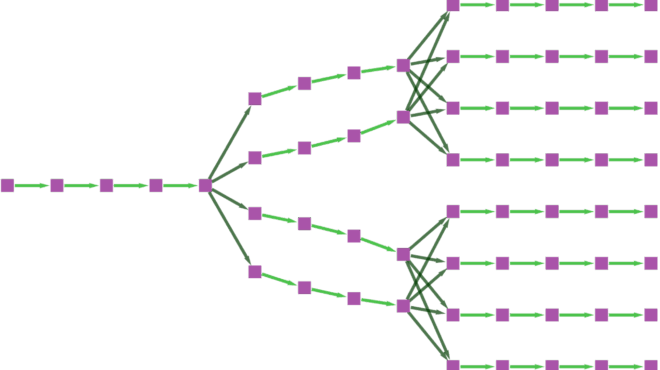

The Saga Pattern

A saga is a sequence of local transactions where each transaction updates the database in a single service and publishes a message or event to trigger the next transaction in the chain. If any local transaction fails, the saga executes a series of compensating transactions to undo the preceding transactions, thus maintaining overall data consistency.

Example: E-Commerce Order Saga

Consider placing an order. This might involve three services: Orders, Payments, and Inventory.

- Orders Service: Creates an order and sets its status to

PENDING. It then publishes anOrderCreatedevent. - Payments Service: Subscribes to

OrderCreated. It attempts to process the payment.- Success: It publishes a

PaymentProcessedevent. - Failure: It publishes a

PaymentFailedevent.

- Success: It publishes a

- Inventory Service: Subscribes to

PaymentProcessed. It reserves the inventory and publishes anInventoryReservedevent. - Orders Service: Subscribes to

InventoryReservedand updates the order status toCONFIRMED.

Handling Failures with Compensating Transactions

What if the Inventory Service finds the item is out of stock after the payment was processed? It would publish an InventoryUnavailable event. The Payments Service would subscribe to this, see that it needs to undo its work for that order, and execute a compensating transaction: refunding the payment. It would then publish a PaymentRefunded event, which the Orders Service would use to mark the order as CANCELLED.

There are two main ways to coordinate a saga:

- Choreography: Each service knows what events to listen for and what events to publish. It’s decentralized and simple for short sagas but can become very difficult to track and debug as the number of steps grows.

- Orchestration: A central orchestrator (which could be a dedicated service or part of the initial service) is responsible for telling each service what to do. It calls the Payment Service, then the Inventory Service, etc. If something fails, the orchestrator is responsible for calling the compensating transactions. This is easier to manage but introduces a central coordinator.

From Monitoring to Observability: Understanding Your System’s Health

In a monolithic application, you could often debug issues by looking at a single set of logs or attaching a debugger. In a microservices architecture, a single user request can traverse dozens of services. This complexity demands a shift from simple monitoring (checking predefined metrics like CPU usage) to full-fledged observability.

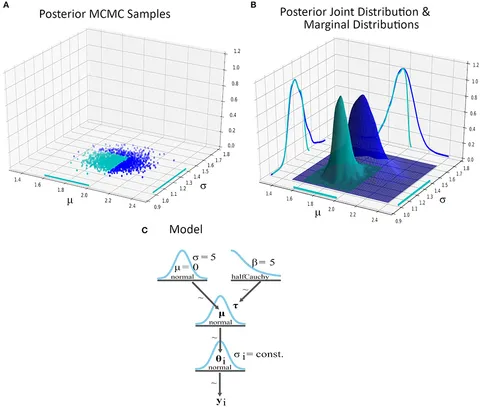

Observability is the ability to understand the internal state of your system by examining its outputs. It rests on three pillars: logging, metrics, and tracing.

Pillar 1: Centralized and Structured Logging

Logs from all your services must be aggregated into a central location (e.g., ELK Stack, Grafana Loki). Furthermore, logs should be structured (e.g., JSON format) rather than plain text. This allows you to easily search, filter, and analyze them. For instance, you can find all log entries for a specific user_id or trace_id across all services.

The Python library structlog is excellent for this:

import structlog

log = structlog.get_logger()

log.info("user_logged_in", user_id=123, service="auth-service", status="success")

# Output: {"user_id": 123, "service": "auth-service", "status": "success", "event": "user_logged_in"}

Pillar 2: Key Performance Metrics

Metrics are numerical representations of data measured over time. Tools like Prometheus are industry standard for collecting and storing metrics. Your Python services can expose an HTTP endpoint with metrics using a client library. Key metrics to track for each service follow the RED method:

- Rate: The number of requests per second.

- Errors: The number of failed requests per second.

- Duration: The distribution of time each request takes (e.g., latency percentiles).

Pillar 3: Distributed Tracing

Tracing is the secret sauce of microservice observability. It allows you to follow a single request’s journey as it hops between services. When a request first enters the system, it’s assigned a unique trace_id. This ID is propagated in the request headers to every service it touches. Each service’s work is recorded as a “span,” and all spans with the same trace_id are stitched together to form a complete trace. This is invaluable for pinpointing bottlenecks and understanding error cascades. Tools like Jaeger and Zipkin, often used with the OpenTelemetry standard, are essential here.

Advanced Deployment and Orchestration Strategies

How you deploy and manage your services in production is just as important as how you build them. Modern systems rely on container orchestration and sophisticated deployment strategies to ensure high availability and minimize risk.

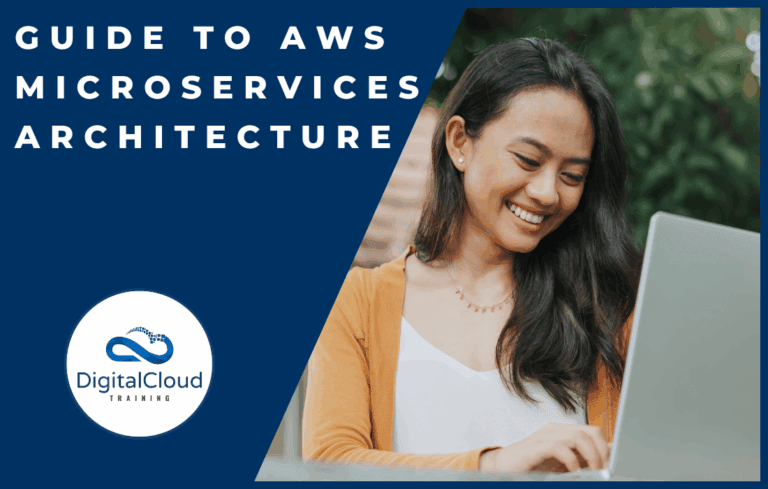

Container Orchestration with Kubernetes

Kubernetes has become the de facto standard for orchestrating containers. It automates the deployment, scaling, and management of your containerized Python applications. It handles service discovery (so services can find each other), load balancing, self-healing (restarting failed containers), and configuration management, freeing developers to focus on building features.

Safe Deployment Strategies

Pushing code directly to production is risky. Advanced deployment strategies help mitigate this risk.

- Blue-Green Deployment: You maintain two identical production environments (“blue” and “green”). If blue is live, you deploy the new version to green. After testing, you switch the router to send all traffic to green. This allows for near-instantaneous rollback if something goes wrong.

- Canary Releases: You gradually roll out the new version to a small subset of users (the “canaries”). You monitor performance and errors closely. If all looks good, you slowly increase the percentage of traffic going to the new version until it handles 100% of the load.

The latest **python news** in the DevOps community often revolves around improving these deployment pipelines, with tools and libraries emerging to make canary releases and other advanced patterns easier to implement within Kubernetes environments.

Conclusion: Embracing Complexity for a Resilient System

Transitioning to a mature Python microservices architecture involves embracing a new set of tools and patterns designed for distributed systems. In this guide, we’ve moved beyond the basics to tackle the core challenges of production-grade systems. By adopting advanced communication patterns like gRPC, ensuring data consistency with the Saga pattern, building a robust observability stack with logging, metrics, and tracing, and leveraging sophisticated deployment strategies, you can build a system that is not just scalable but also resilient, maintainable, and transparent.

The Python ecosystem provides powerful tools for every step of this journey, from FastAPI and gRPC for communication to OpenTelemetry for observability. While the learning curve for these advanced topics can be steep, the payoff in system reliability and developer productivity is immense. The principles discussed here are the foundation upon which you can build truly world-class distributed applications.