Stop Forcing Users to Install Python for Your CLI Tools

I have a confession: for years, I secretly dreaded sharing my Python CLI tools with anyone who wasn’t already a Python developer. It was always the same dance. I’d send them a repo link, and five minutes later, I’d get the Slack message: “Hey, it says pip not found.” Or worse, they’d be on some ancient system Python that broke every dependency I had.

The standard advice used to be “just use pipx.” And sure, pipx is great—I’ve used it for ages. But it still assumes you have a working Python interpreter on your machine. If you’re trying to distribute a utility to a frontend dev or a project manager, asking them to “install Python 3.12 and add it to your PATH” is basically asking them to give up.

That’s why the recent trend of using uv as a standalone bootstrapper has completely changed how I package things. If you haven’t seen this pattern yet—most notably used by tools like Aider—it’s brilliant in its simplicity. It solves the “chicken and egg” problem of Python distribution by removing the user’s need to manage Python entirely.

The “No-Python” Python Install

Here is the logic that finally clicked for me. Instead of telling users to install Python so they can install uv (or pip) so they can install my tool, we flip it.

The user downloads a tiny installer script. That script downloads a standalone binary of uv. Then, uv—which doesn’t need Python to run because it’s written in Rust—downloads a managed Python version specifically for that tool, creates a virtual environment, and installs the package.

The user never touches their system Python. They don’t mess up their messy /usr/bin/python3. They just run one command and get the binary.

I tried replicating this flow last week for a little log parser I wrote. The difference in onboarding friction was night and day. No more “environment externally managed” errors on Debian. No more PATH confusion on Windows.

How the Bootstrapping Works

The magic happens because uv isn’t just a package installer; it’s a Python lifecycle manager. Since Astral released the standalone capabilities, we can treat Python runtimes as just another dependency artifact.

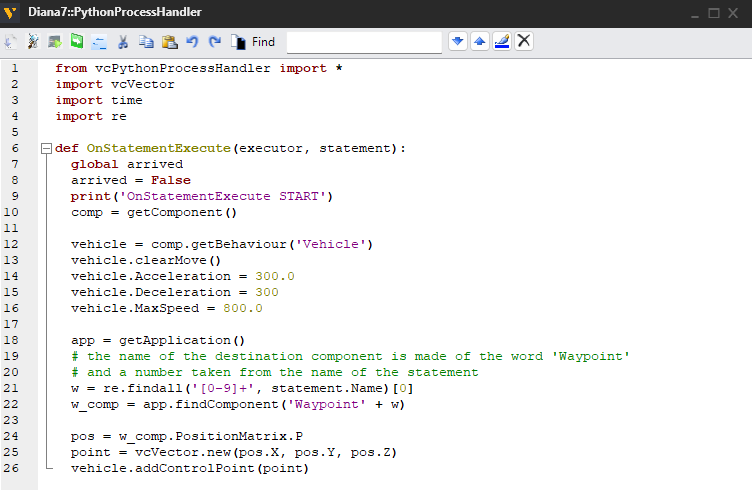

If you look at how a modern bootstrap script works, it’s doing something like this:

- Checks if

uvis present. If not, it fetches the binary to a temp or local bin location. - Runs a command like

uv tool install my-cli --python 3.12. uvsees it needs Python 3.12, fetches a pre-built binary of CPython (which is incredibly fast), links it, and installs the tool.

It sounds heavy, but because uv uses copy-on-write and hard links for its cache, if you install three different tools this way, they share the underlying Python runtime files. It’s surprisingly efficient.

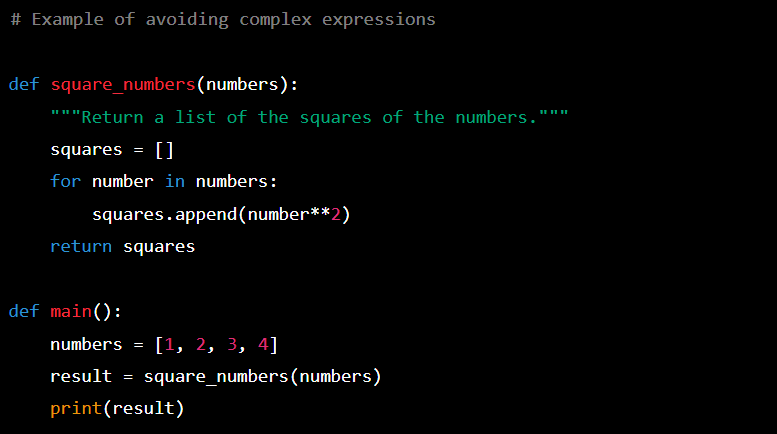

Here is a simplified version of what a Unix-like install script looks like for this pattern. I stripped out the platform checks for brevity, but this is the core logic:

#!/bin/sh

set -e

# 1. Define where we want things

INSTALL_DIR="$HOME/.local/bin"

UV_BIN="$INSTALL_DIR/uv"

# 2. Fetch standalone uv if missing

if [ ! -f "$UV_BIN" ]; then

echo "Bootstrapping uv..."

curl -LsSf https://astral.sh/uv/install.sh | sh

fi

# 3. The magic line: Install the tool using uv's managed python

# We force a specific python version so we know it works

echo "Installing SuperCLI..."

"$UV_BIN" tool install super-cli \

--python 3.12 \

--force

echo "Done! You can now run 'super-cli'"See what’s missing? There’s no python -m venv. There’s no checking if pip is upgraded. The script relies on the fact that uv is a static binary that can handle the rest.

Why This Beats Docker (For CLIs)

You might ask, “Why not just ship a Docker container?”

I’ve been down that road. Docker is great for services, but for CLIs? It’s clunky. You have to map volumes to read local files. You have to deal with weird TTY issues if you want interactive prompts. Plus, spin-up time matters when you’re just trying to grep some logs or lint a file.

This uv approach gives you the isolation of a container (the tool runs in its own venv with its own Python) but the native performance and file system access of a local binary. It feels native.

Handling Updates

Another thing that drove me crazy with pip was updates. Users would install a tool and never update it because they forgot the command or were afraid of breaking dependencies.

With the uv tool paradigm, updating is just:

uv tool upgrade super-cliOr, you can just re-run the install script. Since uv is incredibly fast at resolving dependencies (seriously, the caching is absurd), re-running the installer is often nearly instant if nothing changed. It makes “idempotent installation” actually viable.

The Catch?

Is it perfect? Not entirely. You still need curl (or PowerShell on Windows) to get that initial script running. And some corporate firewalls get grumpy when a script tries to download binaries from the internet. But compared to the alternative—debugging a user’s broken Homebrew setup or explaining why their Debian system packages are conflicting with my requirements.txt—I’ll take this trade-off any day.

If you maintain a Python CLI tool intended for general consumption, stop assuming your users have Python. Just give them a script that handles it. It’s 2026; we really shouldn’t be asking people to manage runtimes anymore.