Advanced Python Testing Strategies – Part 2

Welcome to the second installment of our series on advanced Python testing. In Part 1, we laid the groundwork, but now we venture into the strategies that separate a good test suite from a great one. Master Python testing with pytest, mocking, fixtures, and test-driven development. Learn how to write maintainable, reliable tests for complex Python applications. This is part 2 of our comprehensive series covering advanced techniques and practical implementations. For developers working on sophisticated systems—from data-intensive applications to complex web APIs—a robust testing strategy is not a luxury; it’s the bedrock of maintainability, reliability, and confident deployment. This article will equip you with the patterns and tools to build that foundation, turning your test suite into a powerful asset that accelerates development rather than slowing it down.

We will dissect the “why” and “how” of three core pillars: pytest fixtures for elegant and scalable test setup, mocking for true unit isolation, and the Test-Driven Development (TDD) methodology for designing better, more resilient code from the ground up. By the end, you’ll have actionable insights and practical code examples to elevate your testing practices and build more dependable Python applications.

The Power of Pytest Fixtures: Beyond Simple Setups

In basic testing, it’s common to see repetitive setup and teardown code copied across multiple test functions. This quickly becomes a maintenance nightmare. Pytest fixtures solve this problem with a powerful, modular, and scalable dependency injection system. They are far more than simple setup/teardown helpers; they are the building blocks of a well-structured test suite.

What are Fixtures and Why Use Them?

A fixture is a function that runs before each test function that requests it. It provides a fixed baseline of data, state, or objects for your tests. Unlike the classic setUp() and tearDown() methods found in frameworks like unittest, fixtures are explicitly declared as arguments to your test functions. This explicitness makes it immediately clear what dependencies a test has, improving readability and maintainability.

Key advantages of fixtures include:

- Reusability: Define a fixture once and use it across hundreds of tests in different modules.

- Modularity: Fixtures can use other fixtures, allowing you to build complex test scenarios from smaller, independent components.

- Scalability: Control the lifecycle of a fixture with scopes, optimizing performance for expensive resources like database connections or API clients.

- Clarity: The dependencies of a test are declared in its signature, making the test’s purpose easier to understand.

Fixture Scopes: Managing State and Performance

One of the most powerful features of fixtures is their scope. The scope determines how often a fixture is created and destroyed. Understanding and using the correct scope is crucial for writing efficient tests.

The available scopes, from shortest to longest-lived, are:

function: The default scope. The fixture is set up and torn down for every single test function. Ideal for isolating tests from each other.class: The fixture is created once per test class.module: The fixture is created once per module.package: The fixture is created once per package.session: The fixture is created only once for the entire test run (session). This is perfect for expensive, shared resources like a database connection pool or a web server instance.

Consider a scenario where your tests need to interact with a database. Creating a new database connection for every single test would be incredibly slow. Instead, we can define a session-scoped fixture.

# in tests/conftest.py

import pytest

import sqlite3

@pytest.fixture(scope="session")

def db_connection():

"""

A session-scoped fixture to create a single database connection

for the entire test run.

"""

print("\n--- Setting up DB connection ---")

connection = sqlite3.connect(":memory:")

yield connection

print("\n--- Tearing down DB connection ---")

connection.close()

@pytest.fixture(scope="function")

def db_cursor(db_connection):

"""

A function-scoped fixture that provides a clean cursor for each test.

It depends on the session-scoped db_connection.

"""

cursor = db_connection.cursor()

yield cursor

# No specific teardown needed for cursor, but you could add cleanup here.

Fixtures Using Other Fixtures (Dependency Injection)

The real magic of fixtures is their ability to depend on each other. Pytest automatically resolves this dependency graph. This allows you to compose complex states from simple, reusable parts. For example, to test an endpoint that requires an authenticated user, you might create a chain of fixtures:

- A

test_clientfixture to interact with your web application. - A

new_user_datafixture that returns a dictionary of user details. - A

created_userfixture that uses thedb_connectionandnew_user_datato create a user in the database. - An

authenticated_clientfixture that uses thetest_clientandcreated_userto log the user in and return an authenticated client instance.

A test function can then simply request authenticated_client, and pytest will handle setting up the entire chain of dependencies in the correct order.

Mastering Mocking for True Unit Tests

A fundamental principle of unit testing is isolation. A unit test should focus on a single “unit” of code—typically a function or a method—without relying on external systems like databases, networks, or file systems. Mocking is the technique we use to achieve this isolation by replacing real objects with controlled, predictable stand-ins.

The “Why” of Mocking: Isolating Your Code

Why is isolation so important? Without it, your tests become:

- Slow: Network requests and database queries can take seconds, turning a test suite that should run in milliseconds into one that takes minutes.

- Brittle: If an external API you depend on goes down, your tests will fail, even if your own code is perfectly correct.

- Non-deterministic: The behavior of an external service can change, leading to tests that sometimes pass and sometimes fail without any changes to your codebase.

- Integration Tests in Disguise: When a test interacts with a real database, it’s no longer a unit test; it’s an integration test. While valuable, integration tests are slower and should be a separate part of your testing strategy.

Mocking allows you to simulate the behavior of these external dependencies, ensuring your tests are fast, reliable, and focused solely on the logic of your code unit.

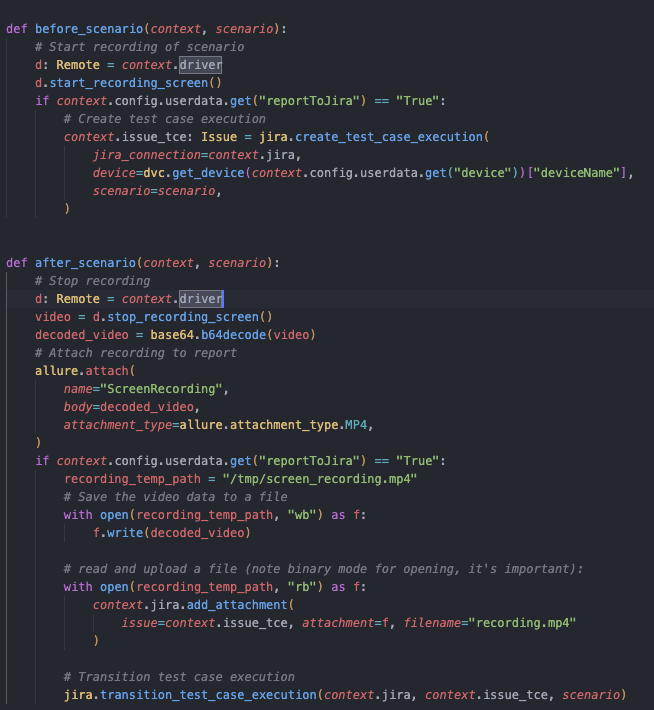

unittest.mock vs. pytest-mock

Python’s standard library includes the powerful unittest.mock module, which provides the `patch` function for replacing objects. While fully functional, its syntax can be a bit verbose, often requiring context managers (with patch(...)) or decorators (@patch(...)).

The pytest-mock plugin provides a more ergonomic experience by integrating mocking directly into the pytest fixture system. It exposes a single fixture, mocker, which is an instance of `unittest.mock`’s `Patcher` class. The key advantage is that its scope is managed automatically by pytest, so you don’t need to worry about manual cleanup.

Practical Mocking Scenarios

Let’s look at a common scenario: testing a function that fetches data from an external API.

Code to be tested:

# in my_app/services.py

import requests

def get_user_posts(user_id):

"""Fetches posts for a given user from an external API."""

response = requests.get(f"https://api.example.com/users/{user_id}/posts")

response.raise_for_status() # Raise an exception for bad status codes

return response.json()

We want to test this function without actually hitting the `api.example.com` server. We can use `mocker` to patch `requests.get`.

The test:

# in tests/test_services.py

from my_app import services

def test_get_user_posts_success(mocker):

"""

Test that get_user_posts correctly processes a successful API response.

"""

# Arrange: Create a mock response object

mock_response = mocker.Mock()

mock_response.json.return_value = [{"id": 1, "title": "Test Post"}]

mock_response.raise_for_status.return_value = None # Do nothing on success

# Arrange: Patch 'requests.get' to return our mock response

mock_get = mocker.patch("my_app.services.requests.get", return_value=mock_response)

user_id = 123

# Act: Call the function we are testing

posts = services.get_user_posts(user_id)

# Assert: Check that our function behaved as expected

mock_get.assert_called_once_with(f"https://api.example.com/users/{user_id}/posts")

assert posts == [{"id": 1, "title": "Test Post"}]

In this test, we have complete control. We define exactly what the API “returns” and verify that our function calls the API with the correct URL and processes the response correctly. The test runs in a fraction of a millisecond because no network call is ever made.

Embracing Test-Driven Development (TDD)

Test-Driven Development (TDD) is a software development process that inverts the traditional “write code, then write tests” model. With TDD, you write the test *before* you write the implementation code. This seemingly small shift has profound implications for code quality, design, and developer confidence.

The TDD Cycle: Red, Green, Refactor

TDD operates on a simple, short, and repetitive cycle:

- Red: Write a small, failing test that defines a new piece of functionality or an improvement. Run the test and watch it fail. This is a critical step because it proves that your test is capable of failing and that the feature doesn’t already exist by accident.

- Green: Write the absolute minimum amount of implementation code necessary to make the test pass. Don’t strive for perfection here; the goal is simply to get to a “green” state. This might even involve hardcoding a return value temporarily.

- Refactor: Now that you have a passing test acting as a safety net, you can clean up the code. Improve the implementation, remove duplication, and enhance clarity, all while continuously running your tests to ensure you haven’t broken anything.

You repeat this cycle for every small piece of functionality, gradually building up a robust and well-tested application.

A Practical TDD Walkthrough

Let’s build a simple password validation function using TDD.

Step 1 (Red): The first requirement is that the password must be at least 8 characters long.

# tests/test_validators.py

import pytest

from my_app.validators import is_password_valid

def test_password_too_short_is_invalid():

assert is_password_valid("short") is False

Running this fails with a `NameError` because `is_password_valid` doesn’t exist.

Step 2 (Green): Let’s make it pass.

# my_app/validators.py

def is_password_valid(password):

return False # The simplest code to make the test pass

The test now passes. It’s not correct yet, but we’re at a green state.

Step 3 (Refactor/Red): Now add a test for a valid password.

# tests/test_validators.py

# ... (previous test) ...

def test_password_long_enough_is_valid():

assert is_password_valid("longenough") is True

This new test fails. Our implementation is no longer sufficient.

Step 4 (Green): Implement the actual logic.

# my_app/validators.py

def is_password_valid(password):

return len(password) >= 8

Now both tests pass. We can continue this cycle, adding tests for requirements like needing an uppercase letter, a number, etc., letting the tests drive our design.

This disciplined approach is frequently discussed in the latest [“python news”] and developer forums, as teams find it leads to more modular and decoupled designs. TDD forces you to think about the public API of your code from the perspective of a consumer (the test) before you get bogged down in implementation details.

Advanced Strategies and Best Practices for a Robust Test Suite

Once you’ve mastered fixtures, mocking, and TDD, you can further enhance your test suite with more advanced patterns that promote efficiency and thoroughness.

Parametrizing Tests with pytest.mark.parametrize

Often, you need to test the same function with a variety of different inputs and expected outputs. Instead of writing a separate test function for each case, you can use `pytest.mark.parametrize` to run the same test function with multiple sets of arguments.

Let’s improve our password validator test:

# tests/test_validators.py

import pytest

from my_app.validators import is_password_valid

@pytest.mark.parametrize("password, expected", [

("short", False), # Too short

("1234567", False), # Too short

("longenough", True), # Just long enough

("muchlongerpassword", True), # Longer is fine

("", False), # Empty string

])

def test_password_length(password, expected):

assert is_password_valid(password) == expected

This single test function will run four times, once for each tuple in the list. Pytest provides clear output indicating which specific case failed, making debugging easy. This pattern dramatically reduces code duplication and makes it trivial to add new test cases.

Structuring Your Test Suite

A well-organized test suite is easier to navigate and maintain. The standard convention is to place all tests in a top-level `tests/` directory. The structure within this directory should mirror your application’s source code structure.

For example:

my_project/

├── my_app/

│ ├── __init__.py

│ ├── models.py

│ └── services.py

├── tests/

│ ├── __init__.py

│ ├── conftest.py # Shared fixtures

│ ├── test_models.py

│ └── test_services.py

└── pytest.ini

Any fixtures that need to be shared across multiple test modules should be placed in a `tests/conftest.py` file. Pytest automatically discovers and makes these fixtures available to all tests without needing any explicit imports.

Conclusion: Building Confidence Through Advanced Testing

Moving beyond basic assertions is a critical step in the journey of a Python developer. The techniques we’ve explored—expressive pytest fixtures, precise mocking for isolation, and the design-centric TDD workflow—are not just about finding bugs. They are about building a safety net that allows you to refactor, innovate, and deploy with confidence. A comprehensive test suite becomes living documentation for your code, clarifying its intended behavior and protecting it against future regressions.

By investing in these advanced strategies, you transform testing from a chore into a core part of the development process. Your tests will drive better design, enable faster iteration, and ultimately lead to more robust, maintainable, and reliable Python applications.