Python Data Pipeline Automation – Part 2

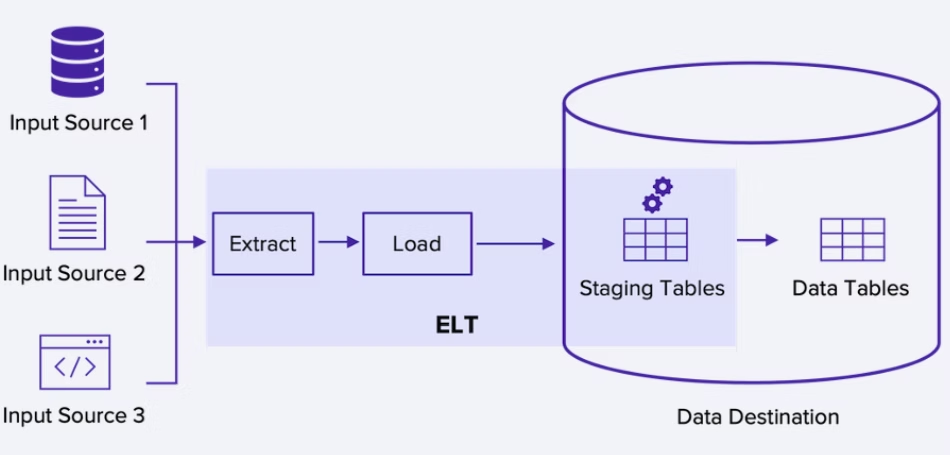

Welcome back to our comprehensive series on building robust data systems. In Part 1, we laid the groundwork for basic Extract, Transform, and Load (ETL) processes using Python. Now, we move beyond simple scripts and into the realm of production-grade automation. This guide is designed to elevate your data processing workflows by focusing on the critical components that ensure reliability, resilience, and trustworthiness: advanced data validation, sophisticated error handling, and comprehensive monitoring.

Automating a data pipeline is one thing; making it resilient enough to run unattended in a production environment is another challenge entirely. A production system must anticipate failure, validate incoming data with rigor, and provide clear visibility into its operational health. Simply letting a script fail silently in the middle of the night is not an option when business decisions depend on the data it produces. In this installment, we will explore the advanced techniques and practical implementations that separate fragile, brittle scripts from dependable, enterprise-ready data pipelines. We’ll cover how to build systems that not only process data but also safeguard its integrity every step of the way.

The Anatomy of a Production-Ready Data Pipeline

Moving a Python data pipeline from a development environment to production involves a significant mindset shift. The goal is no longer just to make the code run successfully once, but to ensure it runs reliably, correctly, and transparently every single time. This requires building a robust framework around the core ETL logic. A production-ready pipeline is a sophisticated system with several layers of defense and observability.

Pillar 1: Proactive Data Validation

The old adage “garbage in, garbage out” is the fundamental truth of data engineering. A pipeline that processes flawed data is not just useless; it’s dangerous. It can lead to incorrect analytics, flawed machine learning models, and poor business decisions. Proactive data validation is the practice of programmatically inspecting and verifying data quality at the very beginning of the pipeline, before any transformations or loading occur. This step acts as a gatekeeper, ensuring that only data meeting predefined quality standards proceeds through the system.

Pillar 2: Resilient Error Handling & Logging

In a production environment, failures are not an “if” but a “when.” APIs become unavailable, database connections drop, file formats change unexpectedly, and data values fall outside expected ranges. A simple script might crash and burn, but a resilient pipeline is designed to handle these failures gracefully. This involves more than a generic try...except block. It means implementing specific exception handling, automated retry mechanisms for transient errors (like network hiccups), and a clear strategy for handling data that repeatedly fails, such as quarantining it in a “dead-letter queue” for manual review.

Coupled with this is robust logging. Simply printing to the console is insufficient. Production pipelines require structured, detailed logs that record every significant event, warning, and error with timestamps, severity levels, and contextual information. These logs are the primary tool for debugging and auditing the pipeline’s behavior over time.

Pillar 3: Comprehensive Monitoring & Alerting

Once a pipeline is deployed, you need to know how it’s performing without manually checking it. This is the domain of monitoring and alerting. Monitoring involves collecting key metrics about the pipeline’s health and performance, such as:

- Execution Time: How long does the pipeline take to run? Is it getting slower?

- Data Volume: How many records were processed? Did it suddenly drop to zero?

- Error Rate: How many tasks or records failed?

- Resource Usage: How much CPU and memory is the pipeline consuming?

Alerting is the automated notification system built on top of these metrics. It proactively informs the engineering team when a metric crosses a critical threshold (e.g., “Alert: Pipeline XYZ has been running for 2 hours, exceeding the 1-hour average”) so that issues can be addressed before they impact downstream consumers.

Deep Dive into Data Validation with Python

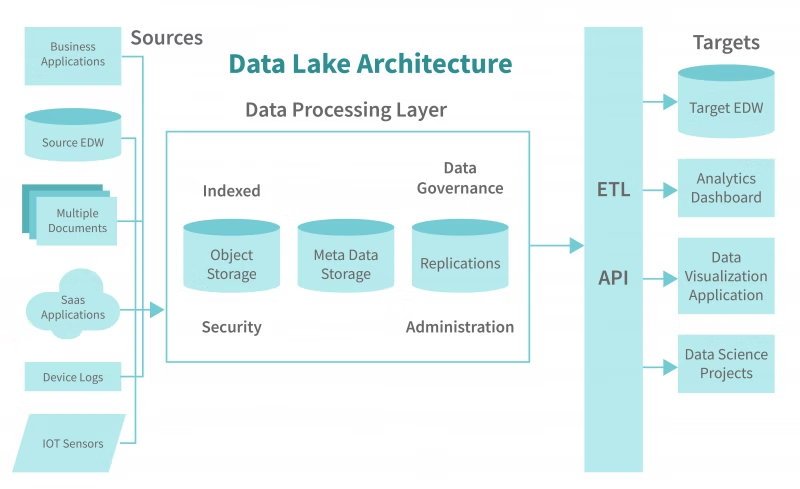

Data validation is your first line of defense against data quality issues. Automating this process using powerful Python libraries ensures consistency and scalability, catching problems early before they corrupt your data warehouse or analytics dashboards. The big news in modern data engineering is the shift towards “data contracts,” where these validation rules are formally defined and enforced.

Key Validation Techniques

A comprehensive validation strategy typically includes several types of checks:

- Schema Validation: Verifies that the data structure is correct. Does it have the expected columns? Are the column names spelled correctly and in the right order?

- Data Type Validation: Ensures that each column contains the correct data type (e.g., a

user_idcolumn should be an integer, not a string). - Range and Constraint Validation: Checks if data values fall within an acceptable range (e.g., an age field must be between 0 and 120) or belong to a set of allowed values (e.g., a

statuscolumn must be one of ‘active’, ‘inactive’, ‘pending’). - Null and Uniqueness Checks: Confirms that critical fields are never empty (e.g., every order must have a

customer_id) and that unique identifiers are, in fact, unique (e.g., no duplicateorder_idvalues).

Practical Example: Validation with Pydantic

While Pandas can be used for basic checks, libraries like Pydantic bring a more structured and explicit approach to data validation, making your code cleaner and more maintainable. Pydantic uses Python type hints to define data schemas and validate data against them.

Imagine we are processing user data from an API. We can define a Pydantic model to represent a valid user record:

import pydantic

from typing import List, Optional

from datetime import date

class UserRecord(pydantic.BaseModel):

user_id: int

email: pydantic.EmailStr # Pydantic has built-in type for email validation

name: str

signup_date: date

age: Optional[int] = pydantic.Field(None, ge=18, le=100) # Optional, must be >= 18 and <= 100 if present

status: str

@pydantic.validator('status')

def status_must_be_valid(cls, v):

allowed_statuses = {'active', 'inactive', 'suspended'}

if v not in allowed_statuses:

raise ValueError(f'Status must be one of {allowed_statuses}')

return v

# Sample raw data from an API (one valid, one invalid)

raw_data = [

{'user_id': 101, 'email': 'test@example.com', 'name': 'Alice', 'signup_date': '2023-10-26', 'age': 30, 'status': 'active'},

{'user_id': 102, 'email': 'invalid-email', 'name': 'Bob', 'signup_date': '2023-10-27', 'age': 17, 'status': 'pending'}

]

valid_records = []

invalid_records = []

for record in raw_data:

try:

validated_record = UserRecord(**record)

valid_records.append(validated_record.dict())

except pydantic.ValidationError as e:

print(f"Validation failed for record {record.get('user_id')}: {e}")

invalid_records.append({'record': record, 'errors': e.errors()})

print("\n--- Valid Records ---")

print(valid_records)

print("\n--- Invalid Records ---")

print(invalid_records)

In this example, Pydantic automatically handles type checking (user_id is an int), format validation (email), range checks (age), and custom logic (status). This approach creates a clear, self-documenting “data contract” that is easy to maintain and test.

Building Resilient Pipelines with Error Handling and Logging

A pipeline that runs perfectly in a controlled environment can fall apart quickly when faced with the unpredictability of real-world data and systems. Building resilience means anticipating failures and designing your code to handle them intelligently.

Implementing Specific Exceptions and Retries

A generic except Exception: clause hides bugs and makes debugging difficult. It’s far better to catch specific exceptions. For example, you should handle a requests.exceptions.ConnectionError from an API call differently than a KeyError from processing a dictionary. For transient issues like network timeouts, implementing an automatic retry mechanism can save the entire pipeline run from failing.

The tenacity library is excellent for this. You can add a simple decorator to a function to make it retry on failure.

import requests

from tenacity import retry, stop_after_attempt, wait_fixed

# This function will be attempted 3 times, with a 2-second wait between attempts

@retry(stop=stop_after_attempt(3), wait=wait_fixed(2))

def fetch_data_from_api(url: str):

"""Fetches data from a potentially unreliable API."""

print("Attempting to fetch data...")

response = requests.get(url, timeout=10)

response.raise_for_status() # Raises an HTTPError for bad responses (4xx or 5xx)

return response.json()

try:

data = fetch_data_from_api("https://api.example.com/data")

print("Successfully fetched data.")

except Exception as e:

print(f"Failed to fetch data after multiple retries: {e}")

The Power of Structured Logging

When your pipeline fails at 3 AM, you don’t want to sift through thousands of messy print statements. You need structured, searchable logs. Python’s built-in logging module is the standard for this. By configuring it to output logs in a format like JSON, you can easily ship them to a log management system (like Elasticsearch, Datadog, or Splunk) for analysis and alerting.

import logging

import sys

import json

# Configure a logger to output JSON

class JsonFormatter(logging.Formatter):

def format(self, record):

log_record = {

"timestamp": self.formatTime(record, self.datefmt),

"level": record.levelname,

"message": record.getMessage(),

"module": record.module,

"funcName": record.funcName,

}

return json.dumps(log_record)

# Get the root logger and configure it

logger = logging.getLogger()

logger.setLevel(logging.INFO)

handler = logging.StreamHandler(sys.stdout)

handler.setFormatter(JsonFormatter())

logger.addHandler(handler)

# --- Example Usage in a Pipeline ---

def process_records(records):

logger.info(f"Starting to process {len(records)} records.")

for record in records:

try:

# ... some processing logic ...

if record['value'] < 0:

raise ValueError("Record value cannot be negative.")

logger.debug(f"Successfully processed record {record['id']}.")

except Exception as e:

# Log the error with context

logger.error(f"Failed to process record {record.get('id')}", extra={"record": record, "error": str(e)})

logger.info("Finished processing records.")

process_records([{'id': 1, 'value': 100}, {'id': 2, 'value': -5}])

This approach provides rich, machine-readable logs that are invaluable for diagnosing problems in a complex, automated system.

Orchestration and Monitoring: The Final Frontier

The final step in productionizing your pipeline is to automate its execution and monitor its health. This is where orchestration tools come in, providing the framework to schedule, execute, and observe your data workflows.

From `cron` Jobs to Modern Orchestrators

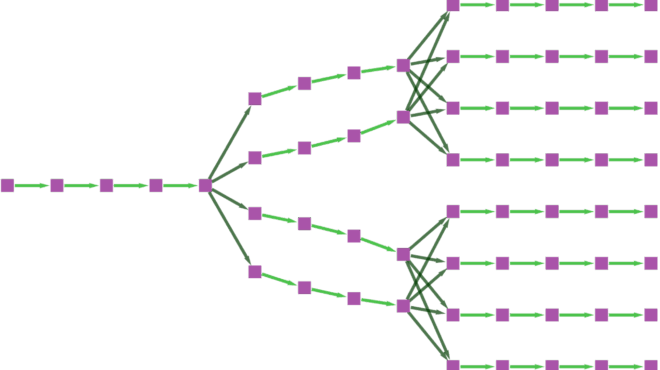

A simple `cron` job can schedule a Python script to run, but it falls short for complex data pipelines. It has no built-in dependency management (e.g., “run Task B only after Task A succeeds”), no easy way to visualize workflows, and limited capabilities for logging and alerting. Modern orchestrators solve these problems by allowing you to define your pipelines as code, typically in the form of a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG).

Choosing Your Orchestration Tool

The Python ecosystem offers several powerful orchestration tools, each with a different philosophy:

- Apache Airflow: The long-standing industry standard. It is incredibly powerful and flexible but can have a steep learning curve. It’s best for large, complex, and relatively static workflows.

- Prefect: Known for its Python-native approach and dynamic workflows. It’s often praised for being more intuitive and flexible than Airflow, making it a great choice for teams that want to move fast.

- Dagster: A “data-aware” orchestrator that focuses on the data assets produced by your pipeline, not just the tasks. It provides excellent tools for data lineage and observability, making it a strong contender, especially for complex data environments. The latest news and development in this area often focus on improving the developer experience and integration with the modern data stack.

Your choice of tool will depend on your team’s specific needs, existing infrastructure, and the complexity of your pipelines. All of them, however, provide the core features needed for production: scheduling, dependency management, logging, retries, and a UI for monitoring.

Conclusion: From Script to System

Transitioning a Python data pipeline from a simple script to a production-grade automated system is a journey of adding layers of resilience and observability. We’ve seen that this process goes far beyond the core ETL logic. It requires a deliberate focus on proactive data validation to ensure data quality, sophisticated error handling and retry mechanisms to build resilience, structured logging to provide deep visibility, and a powerful orchestrator to manage the entire workflow.

By embracing these principles—validation, error handling, logging, and orchestration—you transform your code from a fragile script into a reliable, trustworthy data system. This foundation not only prevents costly data errors but also builds confidence among the stakeholders who depend on your data to make critical decisions. The investment in building robust pipelines pays for itself many times over in stability, maintainability, and, most importantly, trust in the data you provide.