Advanced Python Async Programming Techniques – Part 5

Welcome back to our comprehensive series on asynchronous programming in Python. In the previous installments, we laid the groundwork, moving from basic coroutines and the event loop to more complex patterns of concurrent execution. Now, in Part 5, we venture into the territory that separates functional async code from truly robust, production-ready systems. This guide will delve deep into the advanced techniques you need to manage shared state, handle task lifecycles gracefully, and structure complex applications for scalability and resilience.

Mastering `asyncio` is more than just sprinkling async and await keywords throughout your code. It’s about understanding the subtleties of the event loop, controlling concurrent task execution, and preventing common pitfalls like race conditions and unhandled exceptions. As we explore synchronization primitives, advanced error handling, and scalable architectural patterns, you’ll gain the confidence to build high-performance network clients, web servers, and data processing pipelines. Staying current with these advanced topics is essential, as the evolution of `asyncio` is a constant source of exciting python news and developments within the community. Let’s elevate your Python skills to the next level.

Revisiting the Core: Beyond Simple Concurrency

Before diving into new concepts, it’s crucial to solidify our understanding of how `asyncio` manages groups of tasks. While a simple await some_coroutine() is the fundamental building block, real-world applications almost always involve running multiple operations concurrently. The `asyncio` library provides several powerful tools for this, each with distinct behaviors and use cases.

Choosing the Right Concurrency Primitive: `gather`, `wait`, and `as_completed`

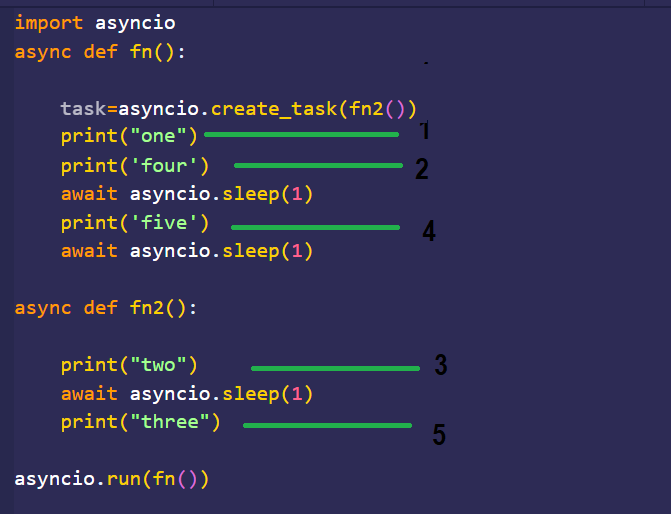

Simply creating tasks with asyncio.create_task() is not enough; you need a strategy to manage them. Let’s compare the three primary functions for handling multiple tasks.

asyncio.gather(*aws): This is often the most straightforward choice. It runs a sequence of awaitables (coroutines or tasks) concurrently. It waits for all of them to complete and returns a list of their results in the same order they were passed in. A critical feature is its “fail-fast” behavior: if any of the tasks raise an exception,gatherimmediately propagates that exception, and the remaining tasks are left running in the background (unless the entire program exits).asyncio.wait(aws, return_when=...): This function offers more fine-grained control. It returns two sets of tasks:doneandpending. Its behavior is governed by thereturn_whenargument, which can beasyncio.ALL_COMPLETED(default),asyncio.FIRST_COMPLETED, orasyncio.FIRST_EXCEPTION. Unlikegather, it does not raise exceptions directly; you must inspect the results of the completed tasks to check for them.asyncio.as_completed(aws): This is an iterator that yields futures as they complete. This is incredibly useful when you want to process results as soon as they become available, rather than waiting for the entire batch to finish. It’s ideal for scenarios where tasks have varying completion times and you want to maximize throughput.

Practical Example: `gather` vs. `as_completed`

Imagine you are fetching data from three different API endpoints with varying response times. Let’s see how these two primitives handle the situation.

import asyncio

import time

import random

async def fetch_data(name, delay):

print(f"Fetching data from {name}...")

await asyncio.sleep(delay)

result = f"Data from {name} (took {delay}s)"

print(f"Finished fetching from {name}")

return result

async def main():

tasks = [

fetch_data("API_A", 2),

fetch_data("API_B", 1),

fetch_data("API_C", 3)

]

print("--- Using asyncio.gather ---")

start_time = time.time()

results = await asyncio.gather(*tasks)

end_time = time.time()

print(f"All results received in {end_time - start_time:.2f} seconds.")

print(results)

print("\n--- Using asyncio.as_completed ---")

# Re-create coroutines as they were consumed

tasks_for_as_completed = [

fetch_data("API_A", 2),

fetch_data("API_B", 1),

fetch_data("API_C", 3)

]

start_time = time.time()

for future in asyncio.as_completed(tasks_for_as_completed):

result = await future

current_time = time.time()

print(f"Processed result: '{result}' at {current_time - start_time:.2f} seconds.")

end_time = time.time()

print(f"All processing finished in {end_time - start_time:.2f} seconds.")

if __name__ == "__main__":

asyncio.run(main())

Running this code will demonstrate that gather waits for the slowest task (API_C, 3 seconds) before returning all results at once. In contrast, as_completed will yield the result from API_B after ~1 second, API_A after ~2 seconds, and finally API_C after ~3 seconds, allowing for immediate, sequential processing of results as they arrive.

Mastering Concurrency: Synchronization Primitives in `asyncio`

While `asyncio` operates on a single thread, the concept of a “race condition” is still highly relevant. Because the event loop can switch between tasks at any await point, two tasks can attempt to modify a shared resource in an interleaved and unpredictable order, leading to corrupted state. To prevent this, `asyncio` provides synchronization primitives analogous to those in traditional multithreading.

asyncio.Lock: Protecting Critical Sections

A Lock provides mutual exclusion. Only one task can “acquire” the lock at a time. Any other task attempting to acquire it will pause (asynchronously) until the lock is released. This is essential for protecting access to shared data.

Example: A Faulty vs. A Safe Counter

Consider a shared counter being incremented by multiple tasks. Without a lock, you can get unexpected results.

import asyncio

shared_counter = 0

async def unsafe_increment():

global shared_counter

current_value = shared_counter

await asyncio.sleep(0.01) # Simulate I/O or other async operation

shared_counter = current_value + 1

async def safe_increment(lock):

global shared_counter

async with lock:

current_value = shared_counter

await asyncio.sleep(0.01)

shared_counter = current_value + 1

async def main():

global shared_counter

# Unsafe version

shared_counter = 0

tasks_unsafe = [unsafe_increment() for _ in range(100)]

await asyncio.gather(*tasks_unsafe)

print(f"Final counter (unsafe): {shared_counter}") # Likely not 100!

# Safe version with Lock

shared_counter = 0

lock = asyncio.Lock()

tasks_safe = [safe_increment(lock) for _ in range(100)]

await asyncio.gather(*tasks_safe)

print(f"Final counter (safe): {shared_counter}") # Will be 100

if __name__ == "__main__":

asyncio.run(main())

In the unsafe version, multiple tasks read the same current_value before any of them have a chance to write the incremented value back, leading to lost updates. The async with lock: block ensures that the read-modify-write operation is atomic, guaranteeing correctness.

asyncio.Semaphore: Limiting Concurrent Access

A Semaphore is like a lock that can be acquired by a specified number of tasks simultaneously. It’s perfect for scenarios where you need to limit concurrency to a resource, such as a database connection pool, a third-party API with a rate limit, or downloading multiple files at once without overwhelming your network connection.

Example: API Rate Limiting

import asyncio

async def call_api(worker_id, semaphore):

print(f"Worker {worker_id} is waiting to acquire semaphore...")

async with semaphore:

print(f"Worker {worker_id} acquired semaphore. Calling API...")

await asyncio.sleep(random.uniform(0.5, 1.5)) # Simulate API call

print(f"Worker {worker_id} finished API call and released semaphore.")

async def main():

# Limit to 3 concurrent API calls

api_semaphore = asyncio.Semaphore(3)

tasks = [call_api(i, api_semaphore) for i in range(10)]

await asyncio.gather(*tasks)

if __name__ == "__main__":

asyncio.run(main())

If you run this code, you’ll observe that no more than three workers are “Calling API…” at any given time, effectively enforcing the rate limit.

Robust Task Management: Lifecycles, Cancellation, and Error Handling

In long-running applications, tasks aren’t just fired and forgotten. You need to manage their entire lifecycle, including graceful cancellation and robust error handling, to prevent resource leaks and silent failures.

Cooperative Task Cancellation

Any task can be cancelled by calling its task.cancel() method. This injects an asyncio.CancelledError exception into the task at the next await point. The key word here is cooperative. A task can choose to ignore the cancellation or, more importantly, perform cleanup operations before exiting.

async def long_running_task():

print("Task started, acquiring resources...")

# Simulate holding a resource like a file or network connection

try:

for i in range(10):

print(f"Working... step {i+1}")

await asyncio.sleep(1)

except asyncio.CancelledError:

print("Task was cancelled. Cleaning up...")

# Simulate cleanup

await asyncio.sleep(0.5)

print("Cleanup complete.")

raise # It's good practice to re-raise CancelledError

finally:

print("This finally block runs regardless of cancellation.")

async def main():

task = asyncio.create_task(long_running_task())

await asyncio.sleep(3.5) # Let it run for a bit

print("Main coroutine deciding to cancel the task.")

task.cancel()

try:

await task # Wait for the task to acknowledge cancellation and finish

except asyncio.CancelledError:

print("Main coroutine caught CancelledError, confirming task is cancelled.")

if __name__ == "__main__":

asyncio.run(main())

The try...except asyncio.CancelledError block is the idiomatic way to handle cleanup. The finally block provides an even more robust guarantee that cleanup code will run.

Handling Exceptions in Concurrent Tasks

A common and dangerous pitfall is the “lost exception.” If you create a task with asyncio.create_task() and never await it or check its result, any exception it raises will be silenced until the task is garbage collected, at which point a warning is logged. This can hide critical bugs in your application.

The correct approach is to always have a strategy for observing task outcomes. Using asyncio.gather is an excellent way to do this.

import asyncio

async def successful_task():

await asyncio.sleep(1)

return "Success"

async def failing_task():

await asyncio.sleep(1)

raise ValueError("Something went wrong!")

async def main():

tasks = [

asyncio.create_task(successful_task()),

asyncio.create_task(failing_task()),

]

# The 'return_exceptions=True' flag is crucial

results = await asyncio.gather(*tasks, return_exceptions=True)

for result in results:

if isinstance(result, Exception):

print(f"Caught an exception: {result}")

else:

print(f"Task finished successfully with result: {result}")

if __name__ == "__main__":

asyncio.run(main())

By setting return_exceptions=True, gather will not fail fast. Instead, it waits for all tasks to finish and places the exception object into the results list in place of the return value, allowing you to iterate through and handle all outcomes gracefully.

Structuring for Scale: Advanced Patterns and Best Practices

As your application grows, you need patterns that decouple components and manage complexity. The producer-consumer pattern is a cornerstone of concurrent system design and fits perfectly with `asyncio`.

The Producer-Consumer Pattern with `asyncio.Queue`

An asyncio.Queue is a thread-safe (or rather, task-safe) data structure for communication between coroutines. “Producers” are tasks that add items to the queue, and “Consumers” are tasks that pull items from the queue and process them. This pattern is fantastic for decoupling work generation from work execution.

import asyncio

import random

async def producer(queue, producer_id):

for i in range(5):

item = f"Item_{i}_from_P{producer_id}"

await asyncio.sleep(random.uniform(0.1, 0.5))

await queue.put(item)

print(f"Producer {producer_id} added '{item}' to the queue.")

print(f"Producer {producer_id} is done.")

async def consumer(queue, consumer_id):

while True:

item = await queue.get()

print(f"Consumer {consumer_id} is processing '{item}'...")

await asyncio.sleep(random.uniform(0.5, 1.0))

print(f"Consumer {consumer_id} finished processing '{item}'.")

queue.task_done()

async def main():

queue = asyncio.Queue()

# Start consumers

consumers = [asyncio.create_task(consumer(queue, i)) for i in range(3)]

# Start producers and wait for them to finish

producers = [producer(queue, i) for i in range(2)]

await asyncio.gather(*producers)

# Wait for the queue to be empty

print("All producers finished. Waiting for consumers to process remaining items...")

await queue.join()

# Cancel the consumer tasks, which are in an infinite loop

for c in consumers:

c.cancel()

if __name__ == "__main__":

asyncio.run(main())

In this example, producers can add work at their own pace, and a pool of consumers processes the work concurrently. queue.join() blocks until every item that was put() into the queue has been processed and had task_done() called for it, providing a simple way to synchronize the shutdown process.

Conclusion: Building on a Solid Foundation

We’ve journeyed deep into the advanced mechanics of Python’s `asyncio` library. By moving beyond basic concurrency and embracing robust patterns for task management, you can build applications that are not only fast but also resilient and scalable. We’ve seen how to choose the right tool for concurrent execution with `gather`, `wait`, and `as_completed`. We’ve learned to prevent race conditions in a single-threaded environment using `Lock` and `Semaphore`. Most critically, we’ve covered the essential patterns for managing task lifecycles through cooperative cancellation and diligent exception handling.

The techniques discussed here—synchronization, graceful shutdowns, and architectural patterns like producer-consumer—are the building blocks of professional-grade asynchronous systems. As you apply these concepts, you’ll find your ability to reason about and construct complex concurrent workflows greatly enhanced. The world of asynchronous Python is constantly evolving, so keeping an eye on the latest python news and official documentation will ensure your skills remain sharp and effective.