Advanced Python Async Programming Techniques

Asynchronous programming in Python, powered by the asyncio library, has transformed how developers handle I/O-bound and high-level structured network code. While many are familiar with the basic async and await keywords, truly unlocking the power of concurrency requires a deeper dive into its more advanced patterns and techniques. This comprehensive guide moves beyond the fundamentals to explore the sophisticated mechanisms that allow you to build highly performant, scalable, and resilient applications. We will dissect the roles of coroutines and the event loop, master concurrent execution patterns like gather and wait, and understand critical concepts such as synchronization primitives and graceful shutdowns.

Whether you’re building a high-traffic web service, a real-time data processing pipeline, or a complex network scraper, these advanced techniques are essential. By understanding how to manage thousands of concurrent operations without the overhead of traditional threading, you can elevate your Python skills to the next level. This exploration is not just academic; it reflects a significant trend in modern software development, a topic frequently highlighted in python news and community discussions, where performance and efficiency are paramount. This article will provide you with the practical examples and in-depth knowledge needed to write sophisticated and efficient asynchronous code.

Understanding the Core Components of asyncio

Before diving into advanced patterns, it’s crucial to have a rock-solid understanding of the fundamental building blocks of asyncio. These components work together to enable cooperative multitasking within a single thread, which is the cornerstone of Python’s approach to asynchronous programming.

Coroutines: The Heart of Async

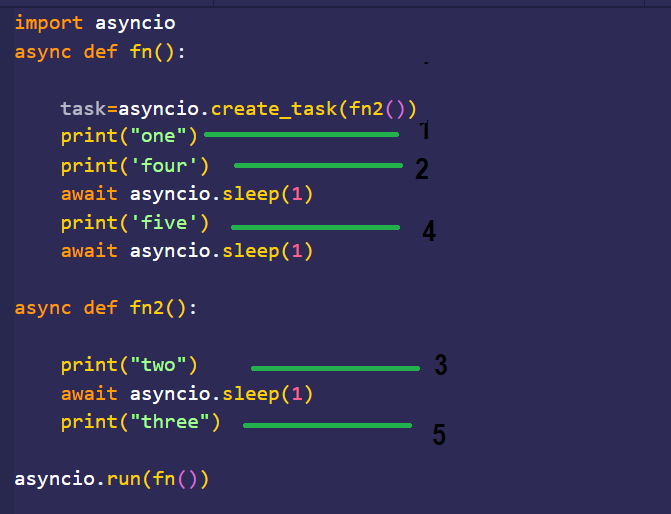

A coroutine is the primary unit of execution in asyncio. Defined with async def, a coroutine is a special type of function that can pause its execution when it encounters an operation that would normally block, such as a network request or a database query. When it awaits an operation (e.g., await asyncio.sleep(1)), it yields control back to the event loop, allowing other tasks to run.

Unlike a regular function, calling a coroutine function doesn’t execute it immediately. Instead, it returns a coroutine object. This object is an awaitable, meaning it can be used with the await keyword inside another coroutine.

import asyncio

async def say_hello(delay, name):

"""A simple coroutine that waits and then prints a message."""

print(f"Starting to say hello to {name}...")

await asyncio.sleep(delay)

print(f"Hello, {name}!")

# Calling the function returns a coroutine object, it doesn't run it yet.

coro = say_hello(2, "Alice")

print(f"Coroutine object created: {coro}")

# To run it, we use asyncio.run()

# asyncio.run(coro)

The Event Loop: The Conductor

The event loop is the engine of any asyncio application. It’s a central scheduler that runs in a single thread and manages all the coroutines. Its job is to:

- Keep track of all running and ready-to-run tasks.

- Execute a task until it hits an

awaitexpression. - When a task is paused, the event loop finds another task that is ready to run and executes it.

- When the awaited operation of a paused task is complete (e.g., a network response arrives), the event loop wakes up that task and schedules it to resume from where it left off.

This process of switching between tasks is called cooperative multitasking. It’s “cooperative” because tasks must explicitly yield control via await. The high-level function asyncio.run(main()) automatically creates and manages the event loop for you, making it the standard way to start an application.

Tasks and Futures: Managing Concurrent Operations

While you can await a coroutine directly, this executes them sequentially. To achieve true concurrency, you need to schedule coroutines to run on the event loop independently. This is done by wrapping them in a Task.

A Task is an object that manages the execution of a coroutine. You create a task using asyncio.create_task(). Once created, the task is scheduled to run on the event loop “in the background” as soon as possible. This allows your main coroutine to continue its own execution without waiting for the new task to complete immediately.

import asyncio

import time

async def background_task():

print("Background task started.")

await asyncio.sleep(3)

print("Background task finished.")

async def main():

print(f"Main started at {time.strftime('%X')}")

# Schedule the background task to run concurrently

task = asyncio.create_task(background_task())

# Do other work while the background task is running

print("Main can do other work now.")

await asyncio.sleep(1)

print("Main did some work.")

# Now, wait for the background task to complete if needed

await task

print(f"Main finished at {time.strftime('%X')}")

asyncio.run(main())

Under the hood, a Task is a subclass of Future. A Future is a lower-level abstraction representing the eventual result of an asynchronous operation. You’ll mostly interact with Task objects, but understanding that they are futures helps in comprehending how asyncio manages results and exceptions.

Mastering Concurrent Execution Patterns

Once you have multiple tasks scheduled, you need patterns to manage them. asyncio provides several powerful functions for orchestrating groups of concurrent tasks, each suited for different scenarios.

Running Tasks Concurrently with asyncio.gather()

asyncio.gather() is the most common and straightforward way to run multiple awaitables concurrently and wait for all of them to finish. It takes a sequence of coroutines or tasks, runs them all, and returns a list of their results in the same order as the inputs.

Use Case: Ideal when you have a fixed number of independent tasks and you need all their results before proceeding.

import asyncio

import aiohttp

async def fetch_url(session, url):

"""Fetches a URL using aiohttp and returns its status."""

async with session.get(url) as response:

print(f"Fetched {url} with status {response.status}")

return response.status

async def main():

urls = [

"https://www.python.org",

"https://www.google.com",

"https://www.github.com"

]

async with aiohttp.ClientSession() as session:

tasks = [fetch_url(session, url) for url in urls]

# gather() runs all tasks concurrently

results = await asyncio.gather(*tasks)

print(f"All results: {results}")

# Note: You need to install aiohttp: pip install aiohttp

# asyncio.run(main())

By default, if any task in gather() raises an exception, all other tasks are cancelled, and the exception is propagated immediately. You can change this behavior with the return_exceptions=True argument, which will cause it to return exception objects in the results list instead of raising them.

Finer Control with asyncio.wait()

asyncio.wait() provides more granular control over a set of concurrent tasks. Unlike gather(), it doesn’t return results directly. Instead, it returns two sets of tasks: those that are `done` and those that are `pending`.

Its key feature is the return_when parameter, which can be:

asyncio.ALL_COMPLETED(default): Waits for all tasks to finish.asyncio.FIRST_COMPLETED: Returns as soon as any single task finishes.asyncio.FIRST_EXCEPTION: Returns when any task raises an exception. If no exceptions, it’s likeALL_COMPLETED.

Use Case: Useful when you need to react as soon as the first of many operations completes, such as querying multiple redundant data sources.

import asyncio

async def long_running_task(delay, name):

await asyncio.sleep(delay)

print(f"Task {name} finished.")

return f"Result from {name}"

async def main():

tasks = [

asyncio.create_task(long_running_task(3, "A")),

asyncio.create_task(long_running_task(1, "B")),

asyncio.create_task(long_running_task(5, "C"))

]

# Wait for the first task to complete

done, pending = await asyncio.wait(tasks, return_when=asyncio.FIRST_COMPLETED)

print(f"Done tasks: {[t.result() for t in done]}")

print(f"Pending tasks: {len(pending)}")

# Clean up pending tasks to avoid "Task was destroyed but it is pending" warnings

for task in pending:

task.cancel()

asyncio.run(main())

Processing Results as They Arrive with asyncio.as_completed()

asyncio.as_completed() provides an iterator that yields futures as they complete. This is perfect when you want to start processing results immediately without waiting for the entire batch of tasks to finish.

Use Case: Ideal for processing a large number of heterogeneous tasks where completion times vary, and you can perform work on each result independently.

import asyncio

import random

async def work_task(name, duration):

print(f"Task {name} started, will take {duration:.2f}s")

await asyncio.sleep(duration)

return f"Task {name} is done!"

async def main():

tasks = [work_task(f"T{i}", random.uniform(0.5, 3.0)) for i in range(5)]

for future in asyncio.as_completed(tasks):

result = await future

print(f"Received result: '{result}'")

asyncio.run(main())

Synchronization Primitives and Real-World Scenarios

Even though asyncio is single-threaded, race conditions can still occur. A task can be paused at an await point, and another task can run and modify a shared state, leading to inconsistencies. To prevent this, asyncio provides synchronization primitives similar to those in the threading module.

Avoiding Race Conditions with Async Primitives

The most common primitive is asyncio.Lock. A lock can be held by only one task at a time. Other tasks attempting to acquire the lock will be blocked (asynchronously) until it is released.

import asyncio

class SharedCounter:

def __init__(self):

self._value = 0

self._lock = asyncio.Lock()

async def increment(self):

async with self._lock:

# This block is a critical section

current_value = self._value

await asyncio.sleep(0.01) # Simulate some I/O work

self._value = current_value + 1

async def worker(counter):

for _ in range(100):

await counter.increment()

async def main():

counter = SharedCounter()

await asyncio.gather(*(worker(counter) for _ in range(10)))

print(f"Final counter value: {counter._value}") # Should be 1000

asyncio.run(main())

Other useful primitives include:

asyncio.Semaphore: Limits the number of tasks that can access a resource concurrently. This is perfect for rate-limiting API calls or controlling access to a connection pool.asyncio.Event: A simple mechanism for one task to signal an event to one or more other tasks, allowing them to proceed.

Practical Application: Building an Async Web Scraper

Let’s combine these concepts to build a more robust web scraper. We’ll use aiohttp for requests and an asyncio.Semaphore to limit concurrent connections, preventing us from overwhelming the server. This kind of efficient network I/O is a frequent topic in python news and performance benchmarks.

import asyncio

import aiohttp

async def fetch_with_semaphore(sem, session, url):

async with sem: # Wait for the semaphore to be available

print(f"Fetching {url}...")

try:

async with session.get(url, timeout=10) as response:

if response.status == 200:

# In a real scraper, you would process the content here

return f"Success: {url}"

else:

return f"Error {response.status}: {url}"

except asyncio.TimeoutError:

return f"Timeout: {url}"

except Exception as e:

return f"Exception for {url}: {e}"

async def main():

# Limit to 10 concurrent requests

semaphore = asyncio.Semaphore(10)

# List of URLs to scrape

urls_to_fetch = [f"http://httpbin.org/delay/{i}" for i in range(1, 4)] * 10

async with aiohttp.ClientSession() as session:

tasks = [fetch_with_semaphore(semaphore, session, url) for url in urls_to_fetch]

results = await asyncio.gather(*tasks)

for res in results:

print(res)

# asyncio.run(main())

Best Practices and Avoiding Common Pitfalls

Writing effective async code requires discipline and awareness of potential traps. Following best practices ensures your application remains responsive and robust.

Don’t Mix Blocking and Async Code

The cardinal rule of asyncio is to never call a blocking I/O function (e.g., requests.get(), time.sleep(), or a standard database driver call) directly within a coroutine. A blocking call will freeze the entire event loop, stopping all other tasks and defeating the purpose of asynchronous programming.

Solution: To integrate blocking code, run it in a separate thread pool using loop.run_in_executor().

import asyncio

import requests

async def main():

loop = asyncio.get_running_loop()

# Run the blocking requests.get() in a thread pool executor

response = await loop.run_in_executor(

None, # Use the default executor

requests.get,

"https://www.python.org"

)

print(f"Blocking request finished with status: {response.status_code}")

# asyncio.run(main())

Graceful Shutdowns

When an application needs to shut down (e.g., due to a KeyboardInterrupt), you should ensure that pending tasks are cleaned up properly. A common pattern is to catch the shutdown signal, gather all pending tasks, cancel them, and wait for them to finish their cancellation process.

import asyncio

async def infinite_worker():

try:

while True:

print("Worker is running...")

await asyncio.sleep(1)

except asyncio.CancelledError:

print("Worker was cancelled.")

async def main():

task = asyncio.create_task(infinite_worker())

try:

await asyncio.sleep(10) # Run for 10 seconds

except KeyboardInterrupt:

print("Shutdown signal received.")

finally:

task.cancel()

# Wait for the task to acknowledge the cancellation

await task

# To test, run this and press Ctrl+C after a few seconds

# asyncio.run(main())

Embrace Async-Native Libraries

The Python async ecosystem is vast and mature. Always prefer libraries that are designed for asyncio from the ground up. Using an async-native library ensures that all I/O operations are non-blocking and integrate seamlessly with the event loop.

- HTTP Clients:

aiohttp,httpx - Databases:

asyncpg(PostgreSQL),motor(MongoDB),aiomysql(MySQL) - Web Frameworks: FastAPI, Starlette, Sanic

Conclusion

Mastering advanced asyncio programming is a journey from understanding simple `await` calls to orchestrating complex concurrent workflows. By leveraging patterns like asyncio.gather(), wait(), and as_completed(), you can manage groups of tasks with precision and efficiency. Understanding and using synchronization primitives like Lock and Semaphore is crucial for preventing data corruption in shared state scenarios. Furthermore, adhering to best practices, especially avoiding blocking calls and ensuring graceful shutdowns, is key to building robust and scalable applications.

Asynchronous programming is not a silver bullet, but for I/O-bound applications, it offers a significant performance advantage over traditional synchronous or multi-threaded models. By applying the techniques covered in this guide, you are well-equipped to design and implement high-performance, concurrent Python applications that can handle the demands of modern software challenges.