Django REST Framework: Advanced API Development Patterns

Django REST Framework (DRF) stands as the cornerstone for building powerful, scalable, and flexible web APIs with Python and Django. While its tutorial provides an excellent entry point, mastering DRF requires moving beyond the basics to embrace advanced patterns that address real-world complexities. Professional API development involves handling intricate data relationships, implementing nuanced business logic, securing endpoints with granular permissions, and ensuring high performance under load. This guide delves deep into these advanced patterns, offering a comprehensive roadmap for developers looking to elevate their skills from building simple CRUD interfaces to architecting enterprise-grade services.

We will explore sophisticated techniques within serializers for dynamic data representation and complex validation. We’ll then dissect advanced ViewSet implementations, covering custom actions, dynamic querysets, and robust filtering. Furthermore, we’ll venture into crucial aspects like custom permissions, rate-limiting (throttling), and API versioning—all hallmarks of a mature and production-ready API. By understanding and applying these patterns, you can build APIs that are not only functional but also maintainable, secure, and highly performant, keeping you updated with the latest in Python news and best practices.

Advanced Serializer Patterns for Complex Data Handling

Serializers are the heart of DRF, responsible for converting complex data types, such as Django model instances, into native Python datatypes that can then be easily rendered into JSON, XML, or other content types. They also handle the reverse process of deserialization and data validation. Advanced serializer patterns unlock the ability to handle virtually any data structure or validation requirement.

Dynamic Field Selection

In many applications, the data required for a list view (e.g., just an ID and name) is a small subset of the data needed for a detail view (all fields). Sending the full data payload for every item in a list is inefficient and increases response times. A dynamic fields serializer allows the client or the view to specify which fields to include in the response.

The original article’s DynamicFieldsSerializer is an excellent starting point. It works by popping fields from the serializer’s fields dictionary post-initialization. This pattern is incredibly useful for optimizing network traffic and tailoring responses to specific use cases.

from rest_framework import serializers

from django.contrib.auth.models import User

class DynamicFieldsModelSerializer(serializers.ModelSerializer):

"""

A ModelSerializer that takes an additional `fields` argument that

controls which fields should be displayed.

"""

def __init__(self, *args, **kwargs):

# Don't pass the 'fields' arg up to the superclass

fields = kwargs.pop('fields', None)

# Instantiate the superclass normally

super().__init__(*args, **kwargs)

if fields is not None:

# Drop any fields that are not specified in the `fields` argument.

allowed = set(fields)

existing = set(self.fields)

for field_name in existing - allowed:

self.fields.pop(field_name)

# Example Usage in a View:

class UserDetailSerializer(DynamicFieldsModelSerializer):

class Meta:

model = User

fields = ['id', 'username', 'email', 'first_name', 'last_name']

# In your ViewSet:

# For a list view, you might do this:

# serializer = UserDetailSerializer(queryset, many=True, fields=('id', 'username'))

# For a detail view:

# serializer = UserDetailSerializer(instance)

Computed Fields and Context-Aware Serialization

Sometimes, the data you want to expose in an API doesn’t correspond directly to a model field. It might be an aggregation, a calculation, or a piece of related data. SerializerMethodField is the perfect tool for this. It allows you to define a method on the serializer (get_<field_name>) that computes the value for the field.

You can make these fields even more powerful by using the serializer’s context. The context is a dictionary passed to the serializer, which typically includes the `request` object. This allows your computed fields to be aware of the current user, query parameters, or other request-specific data.

class UserProfileSerializer(serializers.ModelSerializer):

profile_completion = serializers.SerializerMethodField()

is_following = serializers.SerializerMethodField()

class Meta:

model = User

fields = ['id', 'username', 'profile_completion', 'is_following']

def get_profile_completion(self, obj):

# A simple calculation for profile completeness

fields_to_check = ['first_name', 'last_name', 'email']

completed_count = sum(1 for field in fields_to_check if getattr(obj, field))

return (completed_count / len(fields_to_check)) * 100

def get_is_following(self, obj):

# Accessing the request user from the context

request_user = self.context.get('request').user

if request_user and request_user.is_authenticated:

# Assuming a 'following' relationship exists on the user model

return request_user.following.filter(id=obj.id).exists()

return False

Writable Nested Serializers

One of the most challenging tasks in DRF is handling writes (create/update) for nested relationships. By default, nested serializers are read-only. To support writing, you must override the .create() or .update() methods on the parent serializer.

Imagine a UserProfile model with a one-to-one relationship to the User model. You want to create both the User and their UserProfile in a single API call.

from django.db import transaction

class UserProfileSerializer(serializers.ModelSerializer):

class Meta:

model = UserProfile

fields = ['bio', 'location', 'birth_date']

class UserWithProfileSerializer(serializers.ModelSerializer):

profile = UserProfileSerializer() # Nested serializer

class Meta:

model = User

fields = ['username', 'password', 'email', 'profile']

extra_kwargs = {'password': {'write_only': True}}

@transaction.atomic

def create(self, validated_data):

profile_data = validated_data.pop('profile')

user = User.objects.create_user(**validated_data)

UserProfile.objects.create(user=user, **profile_data)

return user

@transaction.atomic

def update(self, instance, validated_data):

profile_data = validated_data.pop('profile', {})

profile = instance.profile

# Update user instance

instance.username = validated_data.get('username', instance.username)

instance.email = validated_data.get('email', instance.email)

instance.save()

# Update profile instance

profile.bio = profile_data.get('bio', profile.bio)

profile.location = profile_data.get('location', profile.location)

profile.save()

return instance

Using transaction.atomic is crucial here to ensure that both the user and their profile are created successfully, or the entire operation is rolled back if an error occurs.

Advanced ViewSet and Routing Implementation

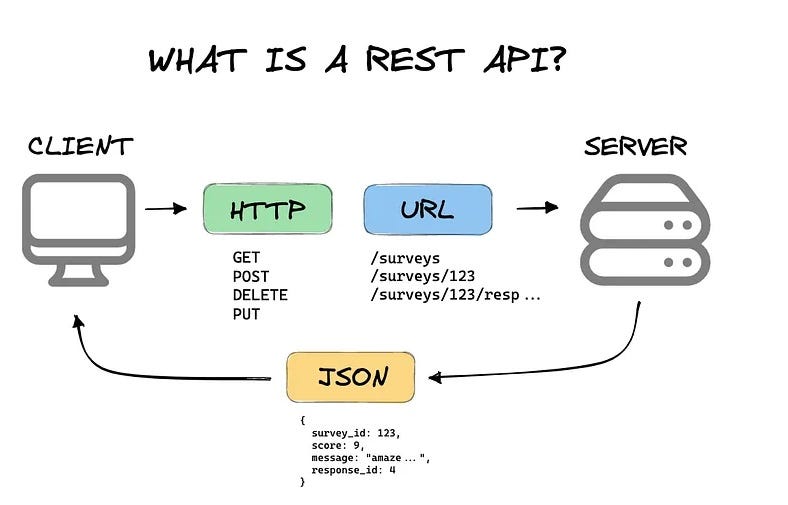

ViewSets abstract away the logic for handling standard HTTP methods (GET, POST, PUT, DELETE) into a single class. Advanced patterns allow you to customize this behavior extensively to fit your application’s logic.

Dynamic QuerySets and Serializer Selection

A common requirement is to serve different data or use different validation logic based on the action (e.g., `list`, `retrieve`, `create`) or the user’s permissions. You can achieve this by overriding get_queryset() and get_serializer_class().

This pattern is powerful for:

- Performance: Use

select_relatedandprefetch_relatedonly for actions that need related data, avoiding expensive joins on list views. - Security: Filter querysets to only show objects the current user is allowed to see.

- Flexibility: Use a simple serializer for creating an object and a more detailed one for retrieving it.

from rest_framework import viewsets

from .serializers import UserCreateSerializer, UserDetailSerializer

class UserViewSet(viewsets.ModelViewSet):

# Default queryset

queryset = User.objects.all()

def get_serializer_class(self):

# Use a different serializer for the 'create' action

if self.action == 'create':

return UserCreateSerializer

# For all other actions (list, retrieve, update, etc.)

return UserDetailSerializer

def get_queryset(self):

"""

Dynamically filter queryset based on user permissions and optimize queries.

"""

queryset = super().get_queryset()

user = self.request.user

# Optimize for the list view to prevent N+1 query problems

if self.action == 'list':

queryset = queryset.prefetch_related('groups')

# Non-staff users can only see their own profile

if not user.is_staff:

queryset = queryset.filter(pk=user.pk)

return queryset

Custom Actions with the @action Decorator

REST is more than just CRUD. Your API often needs to expose business actions that don’t map neatly to HTTP verbs, such as “publish a post” or “reset a password.” The @action decorator is DRF’s solution for adding custom endpoints to a ViewSet.

Actions can be configured for a single object (detail=True) or for the entire collection (detail=False).

from rest_framework import viewsets, status

from rest_framework.decorators import action

from rest_framework.response import Response

from rest_framework.permissions import IsAdminUser

class UserViewSet(viewsets.ModelViewSet):

# ... existing code ...

@action(detail=True, methods=['post'], permission_classes=[IsAdminUser])

def deactivate(self, request, pk=None):

"""A custom action to deactivate a user."""

user = self.get_object()

user.is_active = False

user.save()

return Response({'status': 'user deactivated'})

@action(detail=False, methods=['get'])

def active_users_report(self, request):

"""A collection-level action to get a report."""

active_users = User.objects.filter(is_active=True).count()

return Response({'active_users_count': active_users})

This automatically creates two new routes: /users/{pk}/deactivate/ (for POST) and /users/active_users_report/ (for GET).

Advanced Filtering with django-filter

While DRF’s built-in search and ordering filters are useful, the django-filter library provides a much more powerful and declarative way to filter querysets based on query parameters. You can define a FilterSet class to specify exactly how to filter on each field.

from django_filters import rest_framework as filters

from django.db.models import Q

class UserFilter(filters.FilterSet):

# Filter for users created within a date range

date_joined_after = filters.DateFilter(field_name="date_joined", lookup_expr='gte')

date_joined_before = filters.DateFilter(field_name="date_joined", lookup_expr='lte')

# A custom method filter for a generic search query

search = filters.CharFilter(method='filter_by_all_name_fields')

class Meta:

model = User

fields = ['is_active', 'is_staff']

def filter_by_all_name_fields(self, queryset, name, value):

# A search query that looks in username, first_name, last_name, and email

return queryset.filter(

Q(username__icontains=value) |

Q(first_name__icontains=value) |

Q(last_name__icontains=value) |

Q(email__icontains=value)

)

# In your ViewSet, you simply add it:

class UserViewSet(viewsets.ModelViewSet):

queryset = User.objects.all()

serializer_class = UserDetailSerializer

filter_backends = [filters.DjangoFilterBackend]

filterset_class = UserFilter

Security and Performance Patterns

A professional API must be secure and performant. DRF provides a robust framework for handling authentication, permissions, and throttling, which are essential for protecting your application.

Custom Permissions

DRF’s built-in permissions (e.g., IsAuthenticated, IsAdminUser) are a good start, but real-world applications often need object-level permissions. For example, a user should be able to edit their own profile but not someone else’s. This is achieved by creating a custom permission class.

from rest_framework import permissions

class IsOwnerOrReadOnly(permissions.BasePermission):

"""

Custom permission to only allow owners of an object to edit it.

"""

def has_object_permission(self, request, view, obj):

# Read permissions are allowed to any request,

# so we'll always allow GET, HEAD or OPTIONS requests.

if request.method in permissions.SAFE_METHODS:

return True

# Write permissions are only allowed to the owner of the object.

# Assumes the object has a 'user' attribute.

return obj.user == request.user

Throttling (Rate Limiting)

Throttling is crucial for preventing abuse of your API, such as brute-force attacks or resource exhaustion from a single user. DRF provides a flexible system for rate limiting. You can define default policies in your settings and override them on a per-view basis.

A common pattern is to have a stricter limit for anonymous users and a more generous one for authenticated users.

# in settings.py

REST_FRAMEWORK = {

'DEFAULT_THROTTLE_CLASSES': [

'rest_framework.throttling.AnonRateThrottle',

'rest_framework.throttling.UserRateThrottle'

],

'DEFAULT_THROTTLE_RATES': {

'anon': '100/day', # 100 requests per day for anonymous users

'user': '1000/day' # 1000 requests per day for authenticated users

}

}

# You can also apply more specific throttling using ScopedRateThrottle

# in settings.py

'DEFAULT_THROTTLE_RATES': {

'password_reset': '5/hour'

}

# in your view

from rest_framework.throttling import ScopedRateThrottle

class PasswordResetView(APIView):

throttle_classes = [ScopedRateThrottle]

throttle_scope = 'password_reset'

# ... view logic ...

API Versioning

As your API evolves, you will inevitably need to make breaking changes. API versioning allows you to introduce these changes without disrupting existing client applications. DRF supports several versioning schemes, with URLPathVersioning being a popular and explicit choice.

This strategy includes the version number in the URL (e.g., /api/v1/users/, /api/v2/users/), making it clear which version of the API is being targeted.

# in settings.py

REST_FRAMEWORK = {

'DEFAULT_VERSIONING_CLASS': 'rest_framework.versioning.URLPathVersioning',

'DEFAULT_VERSION': 'v1',

'ALLOWED_VERSIONS': ['v1', 'v2'],

}

# in urls.py

from django.urls import path, re_path

# Example of routing different versions to different views

re_path(r'^api/(?P<version>(v1|v2))/users/$', UserListView.as_view(), name='user-list')

This allows you to maintain separate serializers or view logic for different API versions, ensuring a smooth transition for your users as you roll out updates.

Conclusion

Moving beyond the basics of Django REST Framework unlocks the potential to build truly professional, robust, and scalable APIs. The advanced patterns discussed here—from dynamic serializers and writable nested representations to custom ViewSet actions and granular permissions—are the building blocks of modern web services. By mastering these techniques, you can handle complex business requirements, optimize for performance, and ensure your API is secure and maintainable over the long term. As the world of web development and Python news continues to evolve, a deep understanding of these foundational patterns will enable you to adapt and architect solutions that stand the test of time, delivering real value to your users and your business.