Modern Malware Analysis: Automating Threat Detection with Python and AI

Introduction

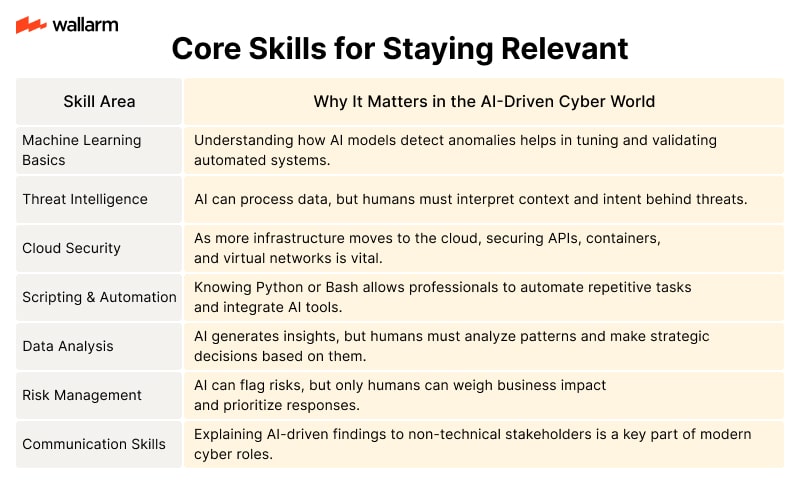

The landscape of cybersecurity is in a perpetual state of flux. As threat actors develop increasingly sophisticated backdoors, rootkits, and polymorphic code, the discipline of **Malware analysis** has had to evolve from manual disassembly to automated, data-driven pipelines. Modern analysis is no longer just about understanding a single binary; it is about correlating behavior across thousands of samples, identifying Command and Control (C2) patterns, and leveraging machine learning to predict malicious intent.

For security researchers and reverse engineers, Python remains the lingua franca of the trade. However, the ecosystem supporting Python is shifting rapidly. With the advent of **GIL removal** and **Free threading** in newer Python versions, the ability to process massive datasets of malware samples in parallel has improved dramatically. Furthermore, the integration of **Local LLM** frameworks and **Edge AI** allows analysts to perform semantic analysis on decompiled code without leaking sensitive data to the cloud.

This article provides a comprehensive technical deep dive into modern malware analysis. We will explore how to build automated static and dynamic analysis pipelines, leverage high-performance data tools like **Polars dataframe** and **DuckDB python**, and utilize next-generation frameworks like **LangChain updates** to assist in deobfuscation. Whether you are investigating financial trojans targeting **Algo trading** systems or analyzing IoT botnets, these techniques are essential.

Section 1: Static Analysis and Infrastructure Setup

Static analysis involves examining the malicious file without executing it. This is the first line of defense and involves extracting metadata, hashing, and analyzing the Portable Executable (PE) structure. Before diving into code, establishing a secure and reproducible environment is critical.

Environment Management and Tooling

Gone are the days of managing dependencies manually. Modern analysts use robust package managers. Tools like **Uv installer**, **Rye manager**, and **PDM manager** ensure that your analysis environment is isolated and reproducible. When building custom analysis tools, using **Hatch build** ensures your scripts can be packaged and deployed to air-gapped systems easily.

Furthermore, code quality in analysis tools is paramount. If your automated scanner fails due to a type error, you might miss a critical indicator of compromise (IOC). implementing **Type hints**, **MyPy updates**, **Ruff linter**, and **Black formatter** ensures your tooling is as reliable as the systems you are protecting. **SonarLint python** can also be integrated into your IDE to catch security vulnerabilities in your own analysis scripts.

Automated PE Header Analysis

The following example demonstrates how to create a robust static analyzer that extracts imports and sections from a Windows executable. We will use `pefile` and structure the data for later analysis with **Pandas updates**.

import pefile

import hashlib

import json

from typing import Dict, Any, List

import pandas as pd

def calculate_hashes(file_path: str) -> Dict[str, str]:

"""

Calculates MD5, SHA1, and SHA256 hashes for a given file.

"""

hashes = {"md5": hashlib.md5(), "sha1": hashlib.sha1(), "sha256": hashlib.sha256()}

with open(file_path, "rb") as f:

while chunk := f.read(8192):

for h in hashes.values():

h.update(chunk)

return {k: v.hexdigest() for k, v in hashes.items()}

def analyze_pe_structure(file_path: str) -> Dict[str, Any]:

"""

Extracts PE sections and imports using static analysis.

"""

try:

pe = pefile.PE(file_path)

except pefile.PEFormatError:

return {"error": "Not a valid PE file"}

analysis_result = {

"hashes": calculate_hashes(file_path),

"sections": [],

"imports": []

}

# Analyze Sections for high entropy (packed code indicators)

for section in pe.sections:

analysis_result["sections"].append({

"name": section.Name.decode().strip('\x00'),

"virtual_address": hex(section.VirtualAddress),

"size": section.SizeOfRawData,

"entropy": section.get_entropy()

})

# Extract Imports

if hasattr(pe, 'DIRECTORY_ENTRY_IMPORT'):

for entry in pe.DIRECTORY_ENTRY_IMPORT:

dll_name = entry.dll.decode().strip('\x00')

for imp in entry.imports:

func_name = imp.name.decode() if imp.name else "ordinal"

analysis_result["imports"].append(f"{dll_name}:{func_name}")

return analysis_result

if __name__ == "__main__":

# Example usage

report = analyze_pe_structure("suspicious_sample.exe")

print(json.dumps(report, indent=4))

# Convert sections to DataFrame for analysis

if "sections" in report:

df = pd.DataFrame(report["sections"])

print("\nSection Analysis:")

print(df[df['entropy'] > 7.0]) # High entropy often indicates packingHandling Obfuscation and Packing

Malware often uses packers to hide its logic. High entropy in PE sections (as checked in the code above) is a classic sign. Advanced analysts are now looking toward **Rust Python** integrations to build high-performance unpackers that can handle throughput that pure Python might struggle with, although **Python JIT** improvements are narrowing this gap.

Section 2: Dynamic Analysis and Network Forensics

Dynamic analysis involves running the malware in a controlled environment (sandbox) to observe its behavior. This includes file system changes, registry modifications, and network traffic.

Network Traffic Analysis with Polars and Scapy

When analyzing a backdoor or a Remote Access Trojan (RAT), understanding the C2 protocol is vital. Modern malware may use complex encoding or encrypted channels. To analyze PCAP (Packet Capture) files efficiently, especially when dealing with gigabytes of traffic logs, **Polars dataframe** and **PyArrow updates** offer significant performance advantages over traditional Pandas.

Below is an example of processing network traffic to identify potential C2 beacons. We use `scapy` for parsing and `polars` for aggregation.

from scapy.all import rdpcap, IP, TCP, UDP

import polars as pl

from datetime import datetime

def extract_packet_data(pcap_file: str) -> pl.DataFrame:

"""

Extracts 5-tuple and timestamp from PCAP for beacon analysis.

Uses Polars for high-performance data manipulation.

"""

packets = rdpcap(pcap_file)

data = []

for pkt in packets:

if IP in pkt:

proto = "TCP" if TCP in pkt else "UDP" if UDP in pkt else "OTHER"

payload_len = len(pkt[TCP].payload) if TCP in pkt else 0

data.append({

"timestamp": float(pkt.time),

"src_ip": pkt[IP].src,

"dst_ip": pkt[IP].dst,

"protocol": proto,

"length": payload_len

})

return pl.DataFrame(data)

def detect_beacons(df: pl.DataFrame, threshold_seconds: int = 5):

"""

Identifies periodic communication patterns indicative of C2 beacons.

"""

# Filter for outbound traffic and sort

# In a real scenario, define internal_subnets to filter accurately

outbound = df.sort("timestamp")

# Calculate time deltas between packets to the same destination

outbound = outbound.with_columns(

pl.col("timestamp").diff().over("dst_ip").alias("time_delta")

)

# Group by destination and calculate variance in time deltas

# Low variance suggests automated beaconing

beacon_candidates = (

outbound.group_by("dst_ip")

.agg([

pl.col("time_delta").std().alias("jitter"),

pl.col("time_delta").mean().alias("avg_interval"),

pl.count().alias("packet_count")

])

.filter(

(pl.col("jitter") < threshold_seconds) &

(pl.col("packet_count") > 10)

)

)

return beacon_candidates

# Usage context

# df = extract_packet_data("traffic.pcap")

# suspects = detect_beacons(df)

# print(suspects)Browser Automation for Web-Based Threats

Many modern threats arrive via the browser or use web technologies. Tools like **Playwright python** and **Selenium news** are essential for visiting malicious URLs in a headless sandbox to capture the final payload or DOM-based obfuscation. **Scrapy updates** allow for broader crawling of threat actor infrastructure.

Section 3: Advanced Techniques: AI and Deobfuscation

The integration of AI into malware analysis is transforming the field. We can now use **Local LLM** models (like Llama 3 or Mistral) running on consumer hardware to explain assembly code or deobfuscate scripts.

Automated Code Explanation with LangChain

Using **LangChain updates** and **LlamaIndex news**, analysts can build “Chat with your Binary” interfaces. This is particularly useful when dealing with languages that are hard to reverse, or when you need to quickly summarize a function’s intent.

The following snippet demonstrates a conceptual setup using LangChain to analyze a decompiled function string. This approach ensures data privacy by using a local model, avoiding the risks of sending malware code to public APIs.

from langchain_community.llms import Ollama

from langchain.prompts import PromptTemplate

from langchain.chains import LLMChain

def analyze_function_semantics(decompiled_code: str):

"""

Uses a Local LLM to explain the purpose of a decompiled function.

Requires Ollama running locally with a model like 'llama3' or 'codellama'.

"""

# Initialize Local LLM

llm = Ollama(model="llama3")

template = """

You are a senior malware analyst. Analyze the following decompiled Python/C code.

Identify:

1. The likely purpose of the function.

2. Any suspicious API calls (encryption, network, process injection).

3. Potential IOCs (Indicators of Compromise).

Code:

{code}

Analysis:

"""

prompt = PromptTemplate(template=template, input_variables=["code"])

chain = LLMChain(llm=llm, prompt=prompt)

response = chain.run(decompiled_code)

return response

# Example malicious-looking code snippet (obfuscated)

suspicious_code = """

import ctypes

def x(s):

return "".join([chr(ord(c) ^ 0x42) for c in s])

# ... execution logic ...

"""

# analysis = analyze_function_semantics(suspicious_code)

# print(analysis)Emerging Technologies and Trends

The ecosystem is expanding beyond standard Python. **Mojo language** promises Python syntax with C-level performance, which could revolutionize how we write heavy-duty unpackers. **MicroPython updates** and **CircuitPython news** are becoming relevant as analysts encounter malware targeting microcontrollers and IoT devices.

For those in **Python finance** and **Algo trading**, protecting against financial malware is critical. These threats often hook into trading platforms. Analysis here often involves **NumPy news** and **Scikit-learn updates** to detect anomalies in high-frequency trading logs that might indicate process injection or data manipulation.

Section 4: Building the Analysis Platform

To scale analysis, you need a platform. Modern web frameworks allow you to build reactive dashboards and APIs for your lab.

API and Dashboard Creation

Using **FastAPI news** or **Litestar framework**, you can build high-performance asynchronous APIs to accept samples. For the frontend, **Reflex app**, **Flet ui**, and **PyScript web** allow Python developers to build interactive UI dashboards without writing JavaScript. **Taipy news** is another contender for building data-driven web apps quickly.

Here is a simple FastAPI implementation for a malware submission endpoint that performs an async scan.

from fastapi import FastAPI, UploadFile, File, BackgroundTasks

from typing import List

import shutil

import os

app = FastAPI(title="Malware Sandbox API")

# Async support in Django (Django async) is great, but FastAPI is often

# preferred for microservices due to speed.

def process_sample(file_path: str):

"""

Background task to run heavy analysis tools.

Could trigger Pytest plugins for behavioral testing.

"""

print(f"Starting analysis on {file_path}")

# Simulate heavy processing (e.g., running Qiskit for crypto analysis or ML models)

# In reality, this would spin up a Docker container or VM.

pass

@app.post("/submit/")

async def submit_sample(

background_tasks: BackgroundTasks,

file: UploadFile = File(...)

):

upload_dir = "./quarantine"

os.makedirs(upload_dir, exist_ok=True)

file_location = f"{upload_dir}/{file.filename}"

with open(file_location, "wb+") as file_object:

shutil.copyfileobj(file.file, file_object)

# Offload the heavy lifting to a background task

background_tasks.add_task(process_sample, file_location)

return {

"filename": file.filename,

"status": "queued",

"message": "File accepted for analysis."

}Database and Querying

For storing analysis results, **Ibis framework** provides a unified API for various backends. **DuckDB python** is increasingly popular for local, analytical workloads on analysis logs because it is fast and serverless.

Best Practices and Optimization

Performance and Concurrency

With **CPython internals** evolving, leveraging **Free threading** (disabling the GIL) in Python 3.13+ allows CPU-bound tasks—like unpacking or cryptographic analysis—to run truly in parallel. If you are using older versions, ensure you use `multiprocessing` rather than `threading`.

Security and Testing

Never run malware on your host machine. Always use VMs or bare-metal sandboxes. For your analysis code, use **Pytest plugins** to ensure your parsers don’t crash on malformed inputs. **Python security** tools like **Bandit** or **SonarLint python** should be part of your CI/CD pipeline to prevent your analysis tools from being exploited by specially crafted malware (e.g., zip bombs or buffer overflows in parsers).

Future-Proofing

Keep an eye on **Qiskit news** and **Python quantum**. While currently niche, post-quantum cryptography will eventually become a standard part of ransomware and C2 protocols. Understanding these libraries now prepares you for the future of **Malware analysis**.

Conclusion

Malware analysis is a complex field that requires a blend of low-level knowledge and high-level automation. By leveraging the modern Python ecosystem—from **Polars** for data processing to **Local LLM** integration for semantic analysis—security researchers can stay ahead of adversaries. The shift toward **Edge AI** and **Python automation** allows for faster detection and more granular insights into threat behavior.

As you build your lab, remember to maintain rigorous code quality with tools like **Ruff** and **MyPy**, and explore emerging technologies like **Mojo** and **Rust Python** to optimize performance. The tools and code snippets provided here serve as a foundation for building a robust, next-generation threat analysis pipeline.