Python Microservices Architecture Guide – Part 2

Welcome back to our comprehensive series on building robust microservices architecture using Python. In Part 1, we laid the groundwork, exploring the fundamental concepts of microservices and why Python, with its rich ecosystem of frameworks and libraries, is an excellent choice for this architectural style. Now, we move beyond the basics to tackle the complex, real-world challenges that arise when you start building and scaling distributed systems. This is where the architectural rubber meets the road.

In this second installment, we will dive deep into the critical pillars that support a resilient and scalable microservices ecosystem. We’ll dissect the intricate dance of service communication, comparing synchronous and asynchronous patterns with practical Python examples. We’ll confront the formidable challenge of maintaining data consistency across disparate services, introducing powerful patterns like Saga. Furthermore, we’ll illuminate the “black box” of distributed systems with a thorough exploration of observability—covering logging, metrics, and tracing. Finally, we’ll map out modern deployment and orchestration strategies using industry-standard tools like Docker and Kubernetes. Prepare to move from theory to implementation as we equip you with the advanced techniques and practical insights needed to build production-grade Python microservices.

Service Communication: The Nervous System of Your Architecture

In a microservices architecture, individual services are useless in isolation. Their collective power is unlocked through communication. However, the way services talk to each other has profound implications for the system’s overall resilience, scalability, and complexity. Choosing the right communication pattern is one of the most critical architectural decisions you will make. The latest python news and discussions in developer communities often revolve around optimizing these communication strategies for performance and reliability.

Synchronous Communication: The Direct Request-Response Model

Synchronous communication is the most intuitive approach. One service makes a request to another and waits for a response, much like a standard function call. The most common protocol for this is HTTP, with services exposing RESTful or gRPC APIs.

When to use it: This pattern is ideal for client-facing operations that require an immediate response, such as a user requesting their profile details or a frontend application fetching product information.

Python Implementation (FastAPI and HTTPX):

Let’s consider an e-commerce application. A `users-service` needs to fetch the order history for a user from an `orders-service`.

The `orders-service` would expose an endpoint:

# in orders-service/main.py

from fastapi import FastAPI

from typing import List, Dict

app = FastAPI()

# Dummy database of orders

db_orders = {

1: [{"order_id": 101, "item": "Laptop", "amount": 1200}, {"order_id": 102, "item": "Mouse", "amount": 25}],

2: [{"order_id": 201, "item": "Keyboard", "amount": 75}],

}

@app.get("/orders/{user_id}")

def get_user_orders(user_id: int) -> List[Dict]:

return db_orders.get(user_id, [])

The `users-service` would then call this endpoint using a robust HTTP client like `httpx`:

# in users-service/main.py

from fastapi import FastAPI, HTTPException

import httpx

app = FastAPI()

ORDERS_SERVICE_URL = "http://orders-service:8000"

@app.get("/users/{user_id}/profile")

async def get_user_profile(user_id: int):

# Basic user info from this service's DB

user_info = {"user_id": user_id, "username": f"user_{user_id}"}

# Call the orders-service to get order history

async with httpx.AsyncClient() as client:

try:

response = await client.get(f"{ORDERS_SERVICE_URL}/orders/{user_id}")

response.raise_for_status() # Raises an exception for 4xx/5xx responses

user_info["orders"] = response.json()

except httpx.RequestError as exc:

# The orders-service might be down or slow

raise HTTPException(status_code=503, detail=f"Error communicating with Orders Service: {exc}")

return user_info

Pitfalls: The primary danger is tight coupling and the risk of cascading failures. If the `orders-service` is slow or down, the `users-service` will also fail or become slow, impacting the end-user. Patterns like Circuit Breakers (using libraries like `pybreaker`) are essential to mitigate this, allowing a service to stop making requests to a failing dependency for a period, preventing system-wide collapse.

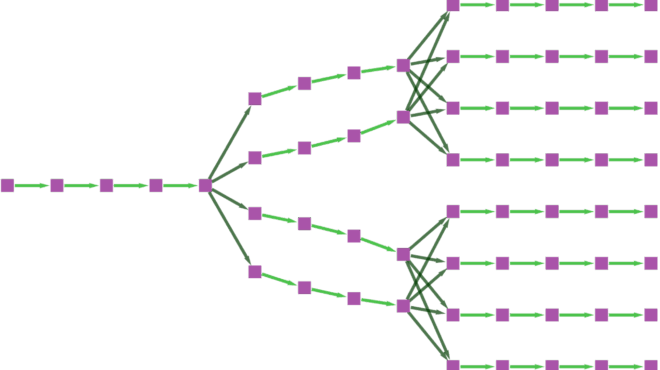

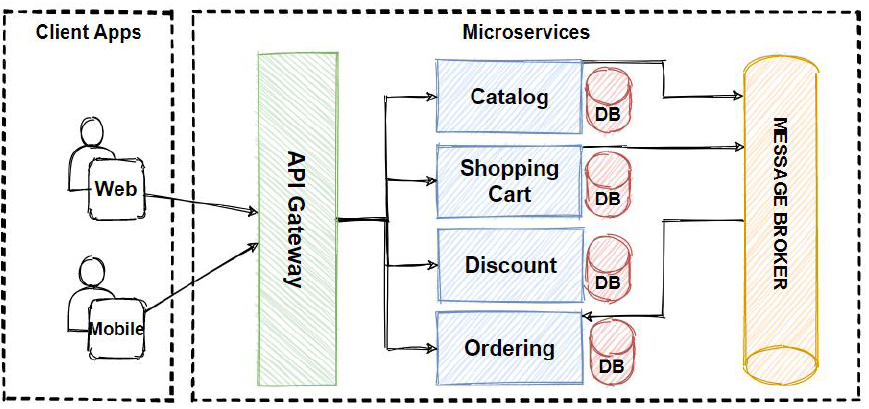

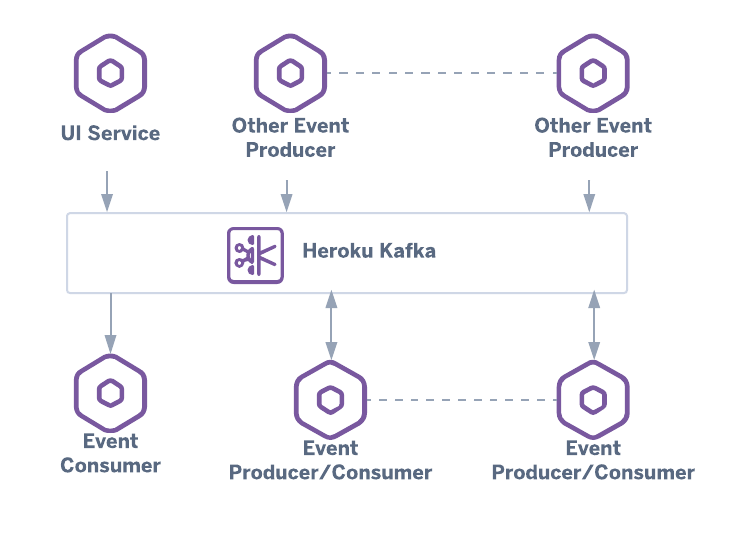

Asynchronous Communication: The Fire-and-Forget Model

Asynchronous communication decouples services by using a message broker (like RabbitMQ or Apache Kafka) as an intermediary. A service publishes an event or a message to the broker and doesn’t wait for a response. Other interested services subscribe to these messages and process them independently.

When to use it: This is perfect for long-running tasks, background processing, or when you want to notify multiple services of an event without being coupled to them. For example, when an order is placed, you might want to notify the inventory, shipping, and notification services simultaneously.

Python Implementation (RabbitMQ and Pika):

When a new order is created in the `orders-service`, it publishes an `OrderCreated` event.

# in orders-service/producers.py

import pika

import json

def publish_order_created(order_details: dict):

connection = pika.BlockingConnection(pika.ConnectionParameters('rabbitmq'))

channel = connection.channel()

# Declare an exchange to publish messages to

channel.exchange_declare(exchange='order_events', exchange_type='fanout')

message = json.dumps(order_details)

channel.basic_publish(exchange='order_events', routing_key='', body=message)

print(f" [x] Sent {message}")

connection.close()

The `inventory-service` listens for these events to update its stock levels.

# in inventory-service/consumers.py

import pika

import json

def start_consuming():

connection = pika.BlockingConnection(pika.ConnectionParameters('rabbitmq'))

channel = connection.channel()

channel.exchange_declare(exchange='order_events', exchange_type='fanout')

# Create an exclusive queue for this consumer

result = channel.queue_declare(queue='', exclusive=True)

queue_name = result.method.queue

channel.queue_bind(exchange='order_events', queue=queue_name)

def callback(ch, method, properties, body):

order_details = json.loads(body)

print(f" [x] Received order. Updating inventory for items: {order_details['items']}")

# ... logic to update inventory database ...

ch.basic_ack(delivery_tag=method.delivery_tag)

channel.basic_consume(queue=queue_name, on_message_callback=callback)

print(' [*] Waiting for order events. To exit press CTRL+C')

channel.start_consuming()

Benefits: This pattern dramatically improves resilience and scalability. If the `inventory-service` is down when an order is placed, the message simply waits in the queue until the service is back online. You can also easily add new services (e.g., a `shipping-service`) that listen to the same event without modifying the `orders-service` at all.

Managing Data Consistency in a Distributed World

One of the hardest problems in microservices is managing data. With the database-per-service pattern, each microservice owns its data and is responsible for its own database. This is great for decoupling, but it eliminates the possibility of using traditional ACID transactions that span multiple services. How do you ensure a business process, like placing an order, completes successfully across services?

The Saga Pattern

The Saga pattern is a design pattern for managing data consistency across microservices in distributed transaction scenarios. A saga is a sequence of local transactions. Each local transaction updates the database within a single service and publishes a message or event to trigger the next local transaction in the next service.

If a local transaction fails, the saga executes a series of compensating transactions to undo the preceding transactions. Let’s model our order placement process as a saga:

- Order Service: Creates an order and sets its status to `PENDING`. Publishes an `OrderCreated` event.

- Payment Service: Consumes `OrderCreated`. Attempts to charge the customer.

- Success: Publishes a `PaymentProcessed` event.

- Failure: Publishes a `PaymentFailed` event.

- Inventory Service: Consumes `PaymentProcessed`. Reserves the items in the order.

- Success: Publishes an `InventoryReserved` event.

- Failure: Publishes an `InventoryReservationFailed` event.

- Order Service: Consumes `InventoryReserved` and sets the order status to `CONFIRMED`. The saga is complete.

Handling Failures with Compensating Transactions:

- If the `Payment Service` publishes `PaymentFailed`, the `Order Service` consumes this event and executes a compensating transaction: it changes the order status to `CANCELLED`.

- If the `Inventory Service` publishes `InventoryReservationFailed`, both the `Payment Service` (to refund the payment) and the `Order Service` (to cancel the order) must consume this event and execute their respective compensating transactions.

This event-driven approach (known as Saga Choreography) is highly decoupled but can become complex to track. An alternative, Saga Orchestration, uses a central coordinator service to tell each participant what to do, which can be simpler to debug but introduces a single point of failure.

Observability: Seeing Inside Your System

A monolithic application is a single box; you can attach a debugger or tail a log file. A microservices architecture is a distributed system of many small, interacting boxes. When a request fails, where did it fail? Why was it slow? Answering these questions requires a deliberate strategy for observability, built on three pillars.

1. Centralized Logging

Each service generates its own logs. To make sense of them, they must be aggregated into a central location. A common stack for this is the ELK Stack (Elasticsearch, Logstash, Kibana) or cloud-native alternatives like AWS CloudWatch Logs or Google Cloud Logging.

Best Practice: Structure your logs as JSON. This makes them machine-readable and easy to parse, filter, and search. Use a library like `python-json-logger`.

# Example of structured logging in Python

import logging

from pythonjsonlogger import jsonlogger

logger = logging.getLogger()

logHandler = logging.StreamHandler()

formatter = jsonlogger.JsonFormatter()

logHandler.setFormatter(formatter)

logger.addHandler(logHandler)

logger.setLevel(logging.INFO)

def process_request(request_id, user_id):

logger.info("Processing request", extra={'request_id': request_id, 'user_id': user_id})

# ... business logic ...

logger.info("Finished processing request", extra={'request_id': request_id})

Crucially, include a correlation ID in every log message. This is a unique identifier generated at the start of a request that is passed between all service calls, allowing you to trace the entire lifecycle of that request through all the logs.

2. Metrics

Metrics are numerical, time-series data that give you a high-level view of your system’s health. Key metrics include:

- Request Rate: The number of requests per second a service is handling.

- Error Rate: The percentage of requests that result in an error.

- Latency: The time it takes for a service to process a request (often measured in percentiles like p95, p99).

- System Metrics: CPU utilization, memory usage, disk I/O.

Tools: Prometheus is the de-facto standard for metrics collection. Your Python services can expose a `/metrics` endpoint using the `prometheus-client` library, which Prometheus then scrapes periodically.

3. Distributed Tracing

While logs and metrics tell you *what* happened, tracing tells you *why*. A distributed trace follows a single request as it propagates through multiple services. It visualizes the entire call graph, showing how long each service took to process its part of the request. This is invaluable for pinpointing bottlenecks and understanding complex interactions.

Tools: OpenTelemetry has become the industry standard for instrumenting applications to generate traces. These traces are then sent to a backend like Jaeger or Zipkin for visualization. Many Python frameworks, including FastAPI and Flask, have OpenTelemetry instrumentation libraries that make this process nearly automatic.

Deployment and Orchestration with Docker and Kubernetes

Managing the deployment lifecycle of dozens or hundreds of services manually is impossible. Automation and standardization are key.

Containerization with Docker

Docker solves the “it works on my machine” problem by packaging an application and all its dependencies (libraries, runtime, system tools) into a standardized unit called a container. This ensures that a service runs identically everywhere, from a developer’s laptop to production servers.

A typical `Dockerfile` for a Python service looks like this:

# Use an official Python runtime as a parent image

FROM python:3.9-slim

# Set the working directory in the container

WORKDIR /app

# Copy the requirements file and install dependencies

COPY requirements.txt .

RUN pip install --no-cache-dir -r requirements.txt

# Copy the rest of the application's code

COPY . .

# Expose the port the app runs on

EXPOSE 8000

# Command to run the application using a production-grade server

CMD ["uvicorn", "main:app", "--host", "0.0.0.0", "--port", "8000"]

Orchestration with Kubernetes

While Docker provides the container, Kubernetes (K8s) provides the “container operating system.” It is a powerful orchestration platform that automates the deployment, scaling, and management of containerized applications. Kubernetes handles:

- Scheduling: Deciding which server (node) in a cluster should run your container.

- Self-healing: Automatically restarting containers that fail.

- Scaling: Scaling the number of container replicas up or down based on load.

- Service Discovery & Load Balancing: Allowing services to find and communicate with each other reliably.

Deploying a service to Kubernetes involves defining its desired state in YAML files. This declarative approach makes infrastructure management repeatable and version-controllable (a practice known as GitOps).

Conclusion: Embracing the Complexity

Transitioning to a Python microservices architecture is not just a technical shift; it’s an operational and organizational one. In this guide, we’ve navigated the critical advanced topics that separate a proof-of-concept from a production-ready system. We’ve seen that for every challenge, the ecosystem provides powerful patterns and tools. For tight coupling in communication, we have asynchronous messaging. For data consistency, we have the Saga pattern. For the opacity of a distributed system, we have the three pillars of observability. And for the chaos of deployment, we have the robust control of Docker and Kubernetes.

Building microservices is a journey of trade-offs. The flexibility and scalability they offer come at the cost of increased complexity. By understanding these challenges and mastering the patterns and tools discussed here, you can harness the full power of Python to build distributed applications that are not just functional, but also resilient, scalable, and maintainable for years to come.