Supercharging Python: A Deep Dive into Parallel Processing and Modern ML Library Enhancements

Introduction

In the world of data science and machine learning, performance is not just a luxury; it’s a necessity. As datasets grow and models become more complex, the single-threaded nature of standard Python code can become a significant bottleneck. This has led to a continuous wave of innovation within the Python ecosystem, focusing on unlocking the full potential of modern multi-core processors. The latest python news isn’t just about new language features, but about the powerful paradigms and library updates that empower developers to write faster, more efficient code.

This article explores one of the most impactful strategies for performance enhancement: parallel processing, specifically through the lens of map-reduce style operations on iterative tasks. We will delve into the practical application of parallelizing “for loops,” a common performance chokepoint in data processing and model training. Furthermore, we’ll connect these techniques to the evolution of specialized machine learning libraries, which are increasingly incorporating advanced parallel capabilities and performance optimizations. By understanding these concepts, you can transform slow, sequential workflows into highly efficient, concurrent pipelines, staying ahead of the curve in a rapidly advancing field.

Section 1: The Core Challenge and the Parallel Solution

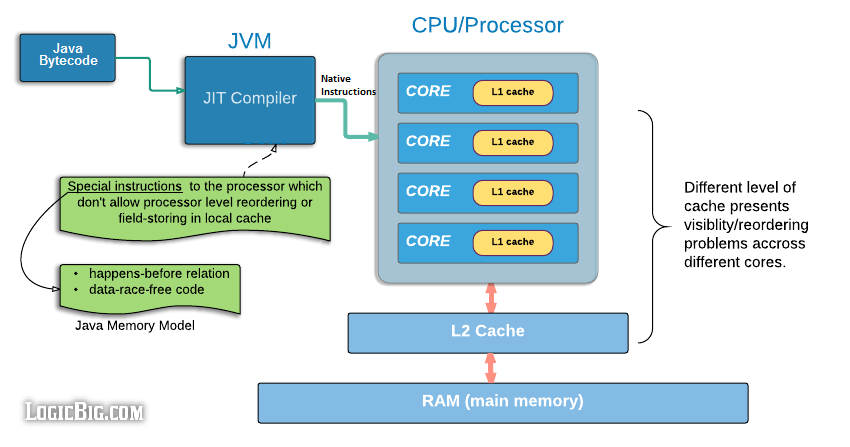

At the heart of Python’s performance discussion lies the Global Interpreter Lock (GIL). The GIL is a mutex that protects access to Python objects, preventing multiple native threads from executing Python bytecodes at the same time. While it simplifies memory management and makes C extensions easier to write, it effectively limits a standard Python program to using a single CPU core at any given moment for CPU-bound tasks. For tasks involving heavy computation—like numerical simulations, image processing, or training machine learning models—this is a major limitation.

From Sequential Loops to Parallel Maps

Consider a common scenario: you have a list of items and need to apply a computationally expensive function to each one. The intuitive approach is a simple for loop:

def process_data(item):

# Simulate a CPU-intensive task

result = 0

for i in range(item * 10**6):

result += i

return result

data = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]

results = []

for item in data:

results.append(process_data(item))

This code works perfectly but is inherently sequential. If each call to process_data takes one second, processing eight items will take eight seconds. On a modern 8-core CPU, seven of those cores sit idle. This is where parallel processing comes in. The goal is to break the “one at a time” constraint by distributing the work across multiple CPU cores.

The Map-Reduce Paradigm

The “Map” paradigm is a powerful and elegant way to think about parallelizing such loops. The idea is to “map” a function onto a sequence of data. Instead of iterating one by one, a parallel map operation applies the function to multiple items in the sequence simultaneously, with each application running in a separate process on a different CPU core. Python’s built-in multiprocessing module provides the perfect tool for this: the Pool object.

multi-core processor diagram – Java Memory Model

A Pool object manages a pool of worker processes. You can submit tasks to this pool, and it will distribute the work among the available processes. Its map method is a direct parallel equivalent of the built-in map function, making the transition from sequential to parallel code remarkably simple.

Section 2: Practical Implementation of Parallel Processing

To overcome the GIL for CPU-bound tasks, Python’s multiprocessing module bypasses it by creating separate processes instead of threads. Each process gets its own Python interpreter and memory space, allowing it to run on a separate CPU core without being constrained by the GIL. Let’s see how to refactor our earlier example to use this powerful feature.

Using `multiprocessing.Pool` for Parallel Maps

The multiprocessing.Pool class provides a convenient way to parallelize the execution of a function across multiple input values. Here is the parallel version of our previous code snippet.

import multiprocessing

import time

# The same CPU-intensive function

def process_data(item):

"""Simulates a CPU-intensive task that takes roughly one second."""

print(f"Processing item {item}...")

result = 0

# Adjust the range to make it take a noticeable amount of time

for i in range(item * 15 * 10**6):

result += i

print(f"Finished item {item}.")

return result

if __name__ == '__main__':

data = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]

# --- Sequential Execution ---

print("--- Starting Sequential Execution ---")

start_time_seq = time.time()

sequential_results = [process_data(item) for item in data]

end_time_seq = time.time()

print(f"Sequential execution took: {end_time_seq - start_time_seq:.2f} seconds")

print("\n" + "="*40 + "\n")

# --- Parallel Execution ---

print("--- Starting Parallel Execution ---")

# Use the number of available CPU cores

num_processes = multiprocessing.cpu_count()

print(f"Creating a pool with {num_processes} processes.")

start_time_par = time.time()

# Create a pool of worker processes

with multiprocessing.Pool(processes=num_processes) as pool:

# map the function to the data; this blocks until all results are ready

parallel_results = pool.map(process_data, data)

end_time_par = time.time()

print(f"Parallel execution took: {end_time_par - start_time_par:.2f} seconds")

# The results are the same, but the execution time is drastically different

# assert sequential_results == parallel_results

On an 8-core machine, the sequential version will take approximately 8 seconds, while the parallel version will take closer to 1-2 seconds (plus a small overhead for process creation). The if __name__ == '__main__': guard is crucial when using multiprocessing on some platforms (like Windows) to prevent child processes from re-importing and re-executing the parent script’s code.

Higher-Level Abstractions: `joblib`

While multiprocessing is powerful, libraries like joblib offer a simpler, higher-level API that is particularly popular in the scientific Python community (it’s used extensively by scikit-learn). It provides a straightforward way to write parallel loops with minimal code changes.

from joblib import Parallel, delayed

import time

# Re-using the same process_data function from before

if __name__ == '__main__':

data = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]

print("--- Starting Joblib Parallel Execution ---")

start_time_joblib = time.time()

# n_jobs=-1 tells joblib to use all available CPU cores

results = Parallel(n_jobs=-1)(delayed(process_data)(item) for item in data)

end_time_joblib = time.time()

print(f"Joblib execution took: {end_time_joblib - start_time_joblib:.2f} seconds")

The Parallel object combined with the delayed function creates a clean and readable generator-based syntax. This approach is often preferred for its simplicity and robust handling of large data by more efficiently managing memory.

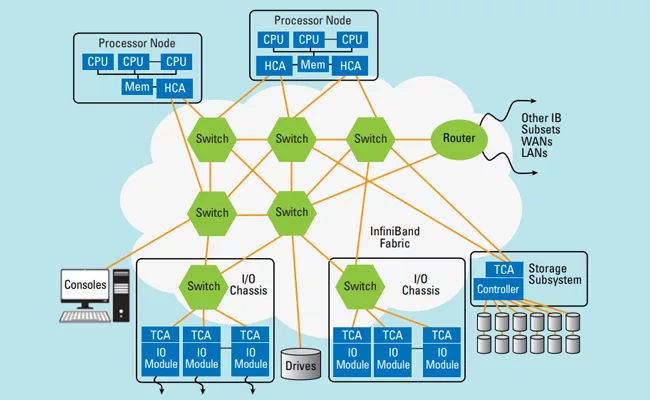

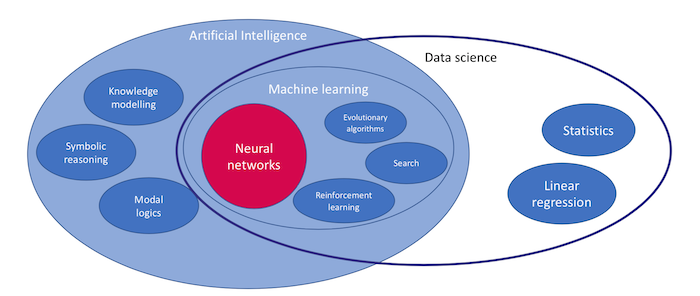

Section 3: The Ripple Effect in Modern Machine Learning Libraries

The principles of parallel processing are not just theoretical exercises; they are foundational to the performance of modern machine learning and data science libraries. The latest python news in this space often revolves around how libraries are evolving to make high-performance computing more accessible to the user, either by parallelizing operations internally or by providing APIs that facilitate user-driven parallelization.

multi-core processor diagram – Why Are There So Many Standards? | 2019-08-13 | Signal Integrity …

Case Study: Parallel Hyperparameter Tuning

A classic and highly practical application of parallel processing is in hyperparameter tuning. When building a model, you often need to test numerous combinations of parameters to find the best-performing set. Since each model training process is independent, this task is “embarrassingly parallel” and a perfect candidate for the map-reduce approach.

Let’s imagine we are using a forecasting library like `ahead` or a neural network library like `nnetsauce`. New versions of such libraries often focus on API clarity and performance. Even if they don’t have built-in parallelism for tuning, their APIs can be easily integrated with tools like `multiprocessing`.

Consider this practical example where we simulate tuning a model by testing different parameters in parallel:

import multiprocessing

import time

import random

# Mock a model training function from a hypothetical library

def train_model(params):

"""

Simulates training a model with a given set of hyperparameters.

Returns the parameters and a simulated validation score.

"""

n_layers = params['n_layers']

learning_rate = params['learning_rate']

print(f"Training model with {n_layers} layers and lr={learning_rate}...")

# Simulate a time-consuming training process

time.sleep(random.uniform(2, 4))

# Simulate a result (e.g., validation accuracy or error)

# Lower is better in this case (e.g., MSE)

score = random.uniform(0.1, 0.5) + (1 / n_layers) - (learning_rate * 2)

print(f"Finished training model with params: {params}. Score: {score:.4f}")

return params, score

if __name__ == '__main__':

# Define the grid of hyperparameters to search

param_grid = [

{'n_layers': 2, 'learning_rate': 0.01},

{'n_layers': 2, 'learning_rate': 0.001},

{'n_layers': 4, 'learning_rate': 0.01},

{'n_layers': 4, 'learning_rate': 0.001},

{'n_layers': 8, 'learning_rate': 0.01},

{'n_layers': 8, 'learning_rate': 0.001},

{'n_layers': 16, 'learning_rate': 0.01},

{'n_layers': 16, 'learning_rate': 0.001},

]

print(f"Starting hyperparameter search for {len(param_grid)} combinations...")

start_time = time.time()

# Use a pool to train models in parallel

with multiprocessing.Pool(processes=multiprocessing.cpu_count()) as pool:

results = pool.map(train_model, param_grid)

end_time = time.time()

print(f"\nParallel hyperparameter search took: {end_time - start_time:.2f} seconds")

# Find the best result

best_params, best_score = min(results, key=lambda item: item[1])

print("\n--- Search Complete ---")

print(f"Best Score: {best_score:.4f}")

print(f"Best Parameters: {best_params}")

This pattern is incredibly powerful. Instead of waiting 20-30 seconds for all 8 models to train sequentially, the entire process completes in the time it takes for the longest single model to train (around 4 seconds), dramatically accelerating the experimental cycle.

Section 4: Best Practices, Pitfalls, and Recommendations

While parallel processing offers immense benefits, it’s not a silver bullet. Applying it correctly requires understanding its trade-offs and potential pitfalls.

multi-core processor diagram – Core discipline-keyword co-occurrence network b) Cross-topic …

When to Parallelize (and When Not To)

- CPU-Bound vs. I/O-Bound Tasks:

multiprocessingis ideal for CPU-bound tasks (e.g., complex calculations, data transformations). For I/O-bound tasks (e.g., waiting for network requests, reading from a database or disk), usingthreadingorasynciois far more efficient, as they can handle thousands of concurrent operations with low overhead while the CPU is idle. - The Cost of Overhead: Creating new processes is not free. It involves memory allocation and data serialization (pickling) to pass arguments between processes. If the task itself is very short (e.g., milliseconds), the overhead of parallelization can make the code slower than a simple sequential loop. Always profile your code first to ensure the task you’re parallelizing is the actual bottleneck.

Common Pitfalls

- Data Serialization: All data passed between the main process and worker processes must be “pickleable.” Complex objects, database connections, or objects containing locks might not serialize, leading to errors. Keep the data passed to worker functions as simple as possible.

- Shared State and Race Conditions: The beauty of

multiprocessingis that it largely avoids issues with shared state by giving each process its own memory. However, if you do need to share state (e.g., usingmultiprocessing.ValueorManager), you must be careful to use locks to prevent race conditions. - Debugging: Debugging parallel code can be challenging. Errors in worker processes might not produce clear stack traces, and print statements can get jumbled. It’s often best to develop and debug your core logic in a sequential manner first before adding the parallelization layer.

Recommendations

- Start Simple: For straightforward parallel loops,

multiprocessing.Pool.mapis an excellent and easy-to-understand starting point. - Embrace High-Level Libraries: For scientific computing, consider

joblibfor its clean syntax and optimizations. - Scale Up with Dask: When your data no longer fits in memory or you need to distribute computations across a cluster of machines, a library like Dask is the next logical step. It provides parallel data structures (like Dask DataFrames) and schedulers that can scale from a single laptop to a large cluster.

- Stay Updated: Keep an eye on the python news and release notes for your favorite data science and ML libraries. Performance is a key focus area, and new versions often bring significant speedups or easier ways to leverage parallelism.

Conclusion

The Python ecosystem is continuously evolving to meet the demands of modern data-intensive computing. While the GIL remains a core aspect of CPython, powerful tools like the multiprocessing module and higher-level libraries like joblib provide effective and accessible ways to break free from single-core limitations. By understanding and applying parallel map-reduce patterns, developers can dramatically accelerate their workflows, from simple data processing tasks to complex machine learning model tuning.

The key takeaway is to think beyond sequential execution. When you encounter a time-consuming for loop, ask yourself if the iterations are independent. If they are, you have a prime candidate for parallelization. As libraries continue to mature, these high-performance techniques are becoming more integrated and easier to use, making it an exciting time to be a Python developer focused on performance and scale.