Advanced Python Async Programming Techniques – Part 2

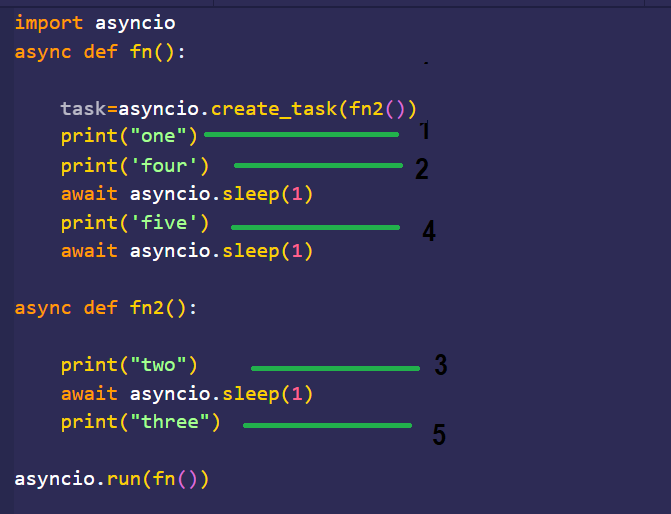

Welcome back to our series on advanced asynchronous programming in Python. In Part 1, we laid the groundwork, exploring the fundamentals of `async def`, `await`, and the basic mechanics of the `asyncio` event loop. Now, it’s time to build upon that foundation and delve into the more sophisticated patterns and tools that `asyncio` provides. This comprehensive guide is designed for developers who are comfortable with the basics and are ready to tackle complex, real-world concurrency challenges. Mastering these techniques will enable you to write more robust, efficient, and scalable I/O-bound applications, from high-performance web servers and API clients to data scraping pipelines and real-time systems. Keeping up with the latest python news reveals a clear trend: proficiency in asynchronous programming is becoming a non-negotiable skill for developers. In this installment, we will explore advanced task management, synchronization primitives, robust error handling strategies, and the crucial technique of integrating blocking code without stalling your entire application. Let’s elevate your Python skills to the next level.

Mastering Concurrent Task Management Beyond `gather`

While `asyncio.gather()` is the workhorse for running multiple coroutines concurrently and waiting for all of them to complete, the `asyncio` library offers more nuanced tools for situations that require finer control over task execution and result processing. Understanding when and how to use `asyncio.wait()`, `asyncio.as_completed()`, and `asyncio.wait_for()` is a hallmark of an advanced async developer.

Fine-Grained Control with `asyncio.wait()`

Unlike `gather()`, which returns a list of results, `asyncio.wait()` provides a lower-level interface that returns two sets of tasks: those that are done and those that are still pending. Its real power lies in the `return_when` argument, which lets you specify the condition for its return.

- `asyncio.ALL_COMPLETED` (default): The function returns after all supplied tasks are finished, similar to `gather()`.

- `asyncio.FIRST_COMPLETED`: The function returns as soon as at least one task completes. This is incredibly useful for scenarios where you are querying multiple redundant data sources and only need the fastest response.

- `asyncio.FIRST_EXCEPTION`: The function returns when the first task raises an exception. If no tasks raise an exception, it behaves like `ALL_COMPLETED`. This is ideal for fail-fast systems.

Consider a scenario where you need to fetch a critical piece of data from one of three mirror APIs. You only need one successful response, and you want it as fast as possible.

import asyncio

import random

async def fetch_from_api(name, delay):

print(f"API {name}: Starting fetch...")

await asyncio.sleep(delay)

print(f"API {name}: Finished fetch.")

return f"Data from {name}"

async def main():

tasks = [

asyncio.create_task(fetch_from_api("A", random.uniform(1, 3))),

asyncio.create_task(fetch_from_api("B", random.uniform(1, 3))),

asyncio.create_task(fetch_from_api("C", random.uniform(1, 3))),

]

done, pending = await asyncio.wait(tasks, return_when=asyncio.FIRST_COMPLETED)

# The first task to finish is now in the 'done' set

for task in done:

print(f"Fastest result: {task.result()}")

# We can now cancel the remaining pending tasks to save resources

print(f"Cancelling {len(pending)} pending tasks...")

for task in pending:

task.cancel()

if __name__ == "__main__":

asyncio.run(main())

Processing Results as They Arrive with `asyncio.as_completed()`

When you have a batch of long-running tasks and want to process their results as they become available rather than waiting for the entire batch to finish, `asyncio.as_completed()` is the perfect tool. It returns an iterator that yields futures as they complete. This pattern is highly effective for web scraping or processing large datasets, as it allows for a continuous flow of work, overlapping I/O with processing.

import asyncio

import time

async def process_item(item_id, duration):

print(f"[{time.monotonic():.2f}] Processing item {item_id}, will take {duration}s.")

await asyncio.sleep(duration)

return f"Result for item {item_id}"

async def main():

tasks = [

process_item(1, 3),

process_item(2, 1),

process_item(3, 2),

]

start_time = time.monotonic()

for future in asyncio.as_completed(tasks):

result = await future

print(f"[{time.monotonic() - start_time:.2f}] Received: {result}")

if __name__ == "__main__":

asyncio.run(main())

# Possible Output:

# [0.00] Processing item 1, will take 3s.

# [0.00] Processing item 2, will take 1s.

# [0.00] Processing item 3, will take 2s.

# [1.01] Received: Result for item 2

# [2.01] Received: Result for item 3

# [3.01] Received: Result for item 1

Notice how the results are processed in the order of completion (item 2, then 3, then 1), not the order of submission.

Synchronization Primitives in an Async World

While `asyncio` uses a single-threaded event loop, preventing true parallel execution of Python code, synchronization is still critical. Race conditions can occur at `await` points, where the event loop can switch context to another task. If two tasks share a mutable state, one task might read the state, `await` an I/O operation, and upon resuming, find that another task has modified the state in the meantime. `asyncio` provides async-compatible versions of classic threading primitives to manage this.

Protecting Critical Sections with `asyncio.Lock`

An `asyncio.Lock` ensures that only one coroutine can execute a specific block of code (a “critical section”) at a time. It’s used to protect shared resources from concurrent modification.

import asyncio

class SharedCounter:

def __init__(self):

self.count = 0

self._lock = asyncio.Lock()

async def increment(self):

async with self._lock:

# This block is the critical section

current_val = self.count

await asyncio.sleep(0.01) # Simulate I/O

self.count = current_val + 1

async def worker(counter):

for _ in range(100):

await counter.increment()

async def main():

counter = SharedCounter()

await asyncio.gather(*(worker(counter) for _ in range(10)))

print(f"Final count: {counter.count}") # Should be 1000

if __name__ == "__main__":

asyncio.run(main())

Without the lock, multiple workers could read the same `current_val`, and after their `await`, they would all overwrite `self.count` with the same new value, leading to a final count far less than 1000.

Limiting Concurrency with `asyncio.Semaphore`

A semaphore is like a lock that can be acquired by a specified number of coroutines simultaneously. This is the ideal tool for rate-limiting or controlling access to a resource pool of a fixed size, such as a database connection pool or a third-party API with a concurrent request limit.

Imagine you are calling an API that only allows 3 concurrent connections.

import asyncio

async def api_call(semaphore, call_id):

async with semaphore:

print(f"Call {call_id}: Acquired semaphore, starting work...")

await asyncio.sleep(random.uniform(0.5, 1.5))

print(f"Call {call_id}: ...Finished work, releasing semaphore.")

return call_id

async def main():

# Limit concurrency to 3 simultaneous calls

api_semaphore = asyncio.Semaphore(3)

tasks = [api_call(api_semaphore, i) for i in range(10)]

await asyncio.gather(*tasks)

if __name__ == "__main__":

asyncio.run(main())

If you run this code, you’ll observe that no more than three “starting work” messages appear at a time without a corresponding “finished work” message, effectively enforcing the rate limit.

Robust Error Handling and Graceful Shutdowns

In a concurrent system, things will inevitably go wrong. An API will time out, a network connection will drop, or data will be malformed. How you handle these exceptions is crucial for the stability of your application.

Managing Exceptions in `asyncio.gather()`

By default, if any task passed to `asyncio.gather()` raises an exception, `gather()` immediately propagates that exception, and the other running tasks are left in a running or finished state. This can make it difficult to retrieve results from the tasks that succeeded. To change this behavior, use the `return_exceptions=True` argument. `gather()` will then wait for all tasks to finish and return a list containing both successful results and exception objects.

import asyncio

async def might_fail(i):

if i % 4 == 0:

raise ValueError(f"Task {i} failed intentionally.")

await asyncio.sleep(1)

return f"Success from task {i}"

async def main():

tasks = [might_fail(i) for i in range(10)]

results = await asyncio.gather(*tasks, return_exceptions=True)

for i, result in enumerate(results):

if isinstance(result, Exception):

print(f"Task {i} failed with error: {result}")

else:

print(f"Task {i} succeeded with result: {result}")

if __name__ == "__main__":

asyncio.run(main())

Understanding and Managing Task Cancellation

Cancellation is a fundamental concept in `asyncio`. A task can be cancelled by calling its `task.cancel()` method. When this happens, an `asyncio.CancelledError` is injected into the task at its next `await` point. A well-behaved coroutine should catch this exception to perform cleanup actions, like closing network connections or releasing locks, before re-raising it.

Graceful shutdown on a `KeyboardInterrupt` (Ctrl+C) is a classic use case.

import asyncio

async def long_running_task():

print("Task starting...")

try:

while True:

await asyncio.sleep(1)

print("Task is running...")

except asyncio.CancelledError:

print("Task was cancelled! Performing cleanup...")

# Simulate cleanup, e.g., closing a file or db connection

await asyncio.sleep(0.5)

print("Cleanup complete.")

raise # It's good practice to re-raise CancelledError

async def main():

task = asyncio.create_task(long_running_task())

try:

await task

except KeyboardInterrupt:

print("\nCtrl+C detected! Cancelling tasks...")

task.cancel()

# Wait for the task to acknowledge cancellation and clean up

await task

if __name__ == "__main__":

try:

asyncio.run(main())

except asyncio.CancelledError:

print("Main coroutine was cancelled.")

Bridging the Gap: Integrating Synchronous Code

A common challenge in real-world Python applications is the need to use libraries that are not `async`-aware. Calling a blocking function, like `requests.get()` or a CPU-intensive computation, directly within a coroutine is disastrous. It will block the entire event loop, freezing all other concurrent tasks and defeating the purpose of `asyncio`.

The Solution: `loop.run_in_executor()`

The correct way to handle blocking code is to run it in a separate thread (for I/O-bound code) or process (for CPU-bound code) using `loop.run_in_executor()`. This function schedules the blocking callable to be run in a `ThreadPoolExecutor` or `ProcessPoolExecutor` and returns an awaitable future, allowing the event loop to continue running other tasks while the blocking call executes.

import asyncio

import requests # A classic synchronous HTTP library

import time

def blocking_http_get(url):

print(f"Executor: Starting blocking request to {url}")

start = time.time()

response = requests.get(url)

duration = time.time() - start

print(f"Executor: Finished blocking request in {duration:.2f}s")

return response.status_code

async def main():

loop = asyncio.get_running_loop()

# Schedule the blocking call in the default ThreadPoolExecutor

future = loop.run_in_executor(

None, blocking_http_get, "https://www.python.org"

)

# Do other async work while the blocking call runs

print("Main: Can do other things while waiting for the executor...")

for i in range(3):

await asyncio.sleep(1)

print(f"Main: ... still doing other things ({i+1})")

status_code = await future

print(f"Main: Blocking call completed with status: {status_code}")

if __name__ == "__main__":

asyncio.run(main())

This pattern is essential for integrating `asyncio` into existing codebases or using powerful libraries that have not yet adopted the `async/await` syntax. The latest python news often discusses the ongoing effort to create async versions of popular libraries, but `run_in_executor` remains a vital and practical tool.

Conclusion: From Theory to Practice

We have journeyed far beyond the basics of `asyncio`, exploring the powerful tools that enable fine-grained control, robust synchronization, and graceful error handling in complex concurrent applications. By mastering patterns like `asyncio.wait()` and `asyncio.as_completed()`, you can optimize for speed or processing efficiency. With synchronization primitives like `Lock` and `Semaphore`, you can safely manage shared state and external resources. Finally, by understanding exception and cancellation handling, and by properly integrating blocking code with `run_in_executor()`, you can build resilient and performant systems that are ready for production challenges. These advanced techniques are the key to unlocking the full potential of asynchronous programming in Python, allowing you to write code that is not only fast but also scalable, maintainable, and robust.