Advanced Python Testing Strategies – Part 3

Welcome to the third installment of our series on mastering Python testing. In today’s complex software landscape, simply writing code that “works” is no longer sufficient. We need code that is reliable, maintainable, and resilient to change. This is where a sophisticated testing strategy becomes not just a best practice, but a necessity. Building upon foundational concepts, this article dives deep into the advanced techniques that separate good tests from great ones. We will explore the practical power of pytest fixtures for elegant setup and teardown, demystify the art of mocking to isolate your code from external dependencies, and walk through a real-world Test-Driven Development (TDD) workflow.

By the end of this guide, you will have a clear understanding of how to leverage these powerful tools to build a comprehensive, automated safety net for your applications. Whether you’re working on a small microservice or a large monolithic application, these strategies will empower you to write tests that provide confidence, improve design, and accelerate your development cycle. Let’s move beyond basic assertions and unlock the full potential of Python’s testing ecosystem.

The Art of Isolation: Mastering Pytest Fixtures

In any non-trivial application, tests rarely operate in a vacuum. They need dependencies: database connections, temporary files, authenticated user objects, or pre-configured class instances. Managing this setup and subsequent cleanup for every single test can lead to repetitive, brittle, and hard-to-read code. This is the problem that pytest fixtures solve with remarkable elegance.

What Are Fixtures and Why Use Them?

A pytest fixture is a function that provides a fixed baseline of data or objects for your tests. Instead of manually creating these resources in each test function, you declare the fixture you need as an argument to your test function, and pytest’s dependency injection system handles the rest. This approach fundamentally changes how you structure your tests, moving from an imperative setup style (e.g., `setUp()` in `unittest`) to a declarative one.

The core benefits of this declarative approach are:

- Modularity and Reusability: A single fixture, like one that provides a database connection, can be defined once in a `conftest.py` file and used across hundreds of tests in your project.

- Explicitness: When you read a test function like `def test_user_profile_update(authenticated_user):`, you immediately know it requires an `authenticated_user` object to run. The dependencies are clear and self-documenting.

- Scalability: Fixtures can depend on other fixtures, allowing you to build up complex state from smaller, reusable components in a clean and manageable way.

Advanced Fixture Scopes for Performance

One of the most powerful features of fixtures is their `scope`. The scope determines how often a fixture is set up and torn down. Understanding and using the correct scope can dramatically speed up your test suite.

function(default): The fixture is run once for each test function. Ideal for objects that need to be in a pristine state for every test.class: The fixture is run once per test class. Useful for setup that can be shared by all methods in a class.module: The fixture is run once per module. Great for setting up resources needed by all tests within a single file.session: The fixture is run only once for the entire test session. This is the key to optimizing slow setup processes, like establishing a database connection or spinning up a Docker container.

Consider a scenario where your tests need to interact with a database. Creating a new connection for every single test is incredibly inefficient. A session-scoped fixture solves this perfectly:

# conftest.py

import pytest

import database_connector

@pytest.fixture(scope="session")

def db_connection():

"""

A single database connection for the entire test session.

"""

print("\n--- Setting up database connection ---")

connection = database_connector.connect()

yield connection # Provide the connection to the tests

print("\n--- Tearing down database connection ---")

connection.close()

# test_user_model.py

def test_create_user(db_connection):

# This test uses the single, session-wide connection

user_id = db_connection.execute("INSERT INTO users ...")

assert user_id is not None

def test_fetch_user(db_connection):

# This test ALSO uses the same connection, without re-running setup

user = db_connection.query("SELECT * FROM users ...")

assert user is not None

In this example, “Setting up database connection” will be printed only once at the beginning of the entire test run, and “Tearing down” will appear once at the very end, saving immense amounts of time.

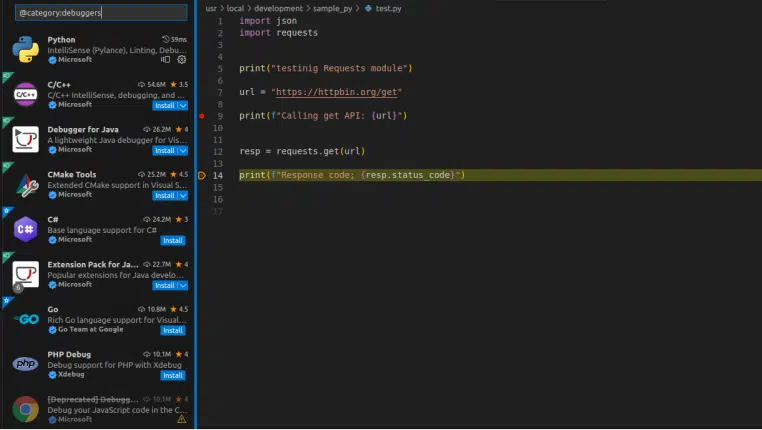

Strategic Deception: Mocking with `unittest.mock` and `pytest-mock`

Modern applications are interconnected. They communicate with external APIs, read from databases, and interact with the file system. While integration tests are crucial for verifying these interactions, unit tests must focus on a single unit of code in isolation. Mocking is the technique we use to achieve this isolation by replacing real dependencies with controlled, predictable fakes.

Why and When to Mock

The goal of mocking is to break external dependencies so you can test your code’s logic without side effects. You should consider mocking when your code interacts with:

- External Networks: Calling a third-party API (e.g., Stripe, Google Maps) in a test is slow, unreliable, and can incur costs.

- Databases: To test a piece of business logic without needing to hit a real database, which speeds up the test and avoids state management issues.

- The File System: Creating and deleting real files can be slow and messy.

- Non-Deterministic Behavior: Functions like `datetime.datetime.now()` or `random.randint()` produce different results on each run, making assertions impossible. Mocking them allows you to control their output.

`pytest-mock` and the `mocker` Fixture

While Python’s standard library includes the powerful `unittest.mock` module, the `pytest-mock` plugin provides a convenient `mocker` fixture that integrates it seamlessly into the pytest ecosystem. The `mocker` fixture handles the teardown of patches automatically, preventing mock “leakage” between tests.

Let’s imagine a function that fetches weather data from an external service and processes it.

# weather_service.py

import requests

def get_temperature(city):

"""Fetches the current temperature for a given city."""

try:

response = requests.get(f"https://api.weather.com/data?city={city}")

response.raise_for_status() # Raise an exception for bad status codes

data = response.json()

# Let's assume the API returns {'main': {'temp': 25}} for Celsius

return f"The temperature in {city} is {data['main']['temp']}°C."

except requests.exceptions.RequestException as e:

return f"Error fetching weather: {e}"

# test_weather_service.py

from weather_service import get_temperature

def test_get_temperature_success(mocker):

"""

Test the successful path by mocking the requests.get call.

"""

# Create a mock response object

mock_response = mocker.Mock()

mock_response.json.return_value = {"main": {"temp": 15}}

mock_response.raise_for_status.return_value = None # Do nothing on success

# Patch 'requests.get' to return our mock response

mock_get = mocker.patch("requests.get", return_value=mock_response)

# Call the function under test

result = get_temperature("London")

# Assert that our function behaved correctly

assert result == "The temperature in London is 15°C."

# Assert that the external API was called as expected

mock_get.assert_called_once_with("https://api.weather.com/data?city=London")

Here, we completely avoided a real network call. We controlled the exact data (`{“main”: {“temp”: 15}}`) returned by the fake API, allowing us to test our function’s string formatting logic in perfect isolation. Furthermore, `mock_get.assert_called_once_with(…)` verifies that our code is interacting with the dependency correctly.

Building with Confidence: A Practical TDD Workflow

Test-Driven Development (TDD) is a software development process that inverts the traditional “write code, then write tests” model. It’s a discipline that encourages simple design and inspires confidence by ensuring every piece of code is backed by a failing test before it’s even written.

The Red-Green-Refactor Cycle

TDD revolves around a simple, repetitive cycle:

- Red: Write a small, failing automated test for a new feature or improvement. The test will fail because the implementation code doesn’t exist yet. This step forces you to think clearly about the desired interface and behavior *before* writing any code.

- Green: Write the absolute minimum amount of implementation code required to make the test pass. The goal here is not elegance or perfection, but simply to get to a passing state.

- Refactor: With the safety of a passing test, you can now clean up and improve the code you just wrote (both the implementation and the test itself). You can rename variables, extract methods, or remove duplication, all while continuously running the tests to ensure you haven’t broken anything.

This cycle produces a comprehensive suite of tests as a natural byproduct of the development process, serving as living documentation and a powerful regression safety net.

TDD in Action: Building a Shopping Cart

Let’s build a simple `ShoppingCart` class using TDD.

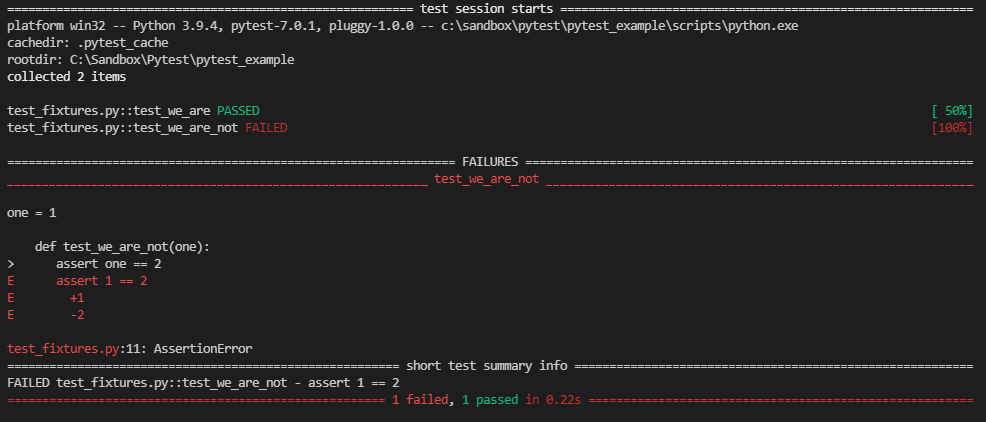

Step 1 (Red): Write a failing test for adding an item.

# test_cart.py

from shopping_cart import ShoppingCart

def test_can_add_item_to_cart():

cart = ShoppingCart()

cart.add_item("apple", 2.50)

assert len(cart.items) == 1

Running this fails with `ImportError: cannot import name ‘ShoppingCart’`. Perfect.

Step 2 (Green): Make the test pass.

# shopping_cart.py

class ShoppingCart:

def __init__(self):

self.items = []

def add_item(self, name, price):

self.items.append({"name": name, "price": price})

Now, the test passes. The code isn’t perfect, but it works.

Step 3 (Red): Write a failing test for calculating the total.

# test_cart.py

# ... (add to the existing file)

def test_can_calculate_cart_total():

cart = ShoppingCart()

cart.add_item("apple", 2.50)

cart.add_item("banana", 1.50)

assert cart.get_total() == 4.00

This fails with `AttributeError: ‘ShoppingCart’ object has no attribute ‘get_total’`.

Step 4 (Green): Make the new test pass.

# shopping_cart.py

class ShoppingCart:

def __init__(self):

self.items = []

def add_item(self, name, price):

self.items.append({"name": name, "price": price})

def get_total(self):

return sum(item["price"] for item in self.items)

Both tests now pass. We have a working implementation.

Step 5 (Refactor): Improve the code.

The code is simple and looks good. The test code is also clean. In a more complex scenario, this is where we would look for code smells, duplication, or opportunities to improve clarity, all while re-running our tests to ensure we don’t introduce regressions.

Beyond Single Scenarios: Advanced Testing Patterns

As your test suite grows, you’ll encounter situations where standard tests feel inefficient. Advanced patterns like parametrization and property-based testing can help you achieve better coverage with less code.

Scaling Tests with `pytest.mark.parametrize`

Often, you need to test the same piece of logic with a variety of different inputs. Instead of writing a separate test function for each input, pytest’s `parametrize` marker lets you run the same test function with multiple argument sets.

# utils.py

def is_valid_email(email):

return "@" in email and "." in email.split("@")[-1]

# test_utils.py

import pytest

from utils import is_valid_email

@pytest.mark.parametrize("email, expected", [

("test@example.com", True),

("user.name@domain.co.uk", True),

("invalid-email", False),

("test@.com", False),

("test@domain.", False),

("@domain.com", False),

])

def test_is_valid_email(email, expected):

assert is_valid_email(email) == expected

This single test function will run six times, once for each tuple in the list. Pytest provides clear output on which specific case fails, and adding new test cases is as simple as adding a new line to the list.

A Glimpse into Property-Based Testing

Property-based testing takes parametrization a step further. Instead of you providing a list of example inputs, you define the *properties* or *invariants* of your code, and a library like `Hypothesis` generates hundreds of random, simplified examples to try and prove your properties wrong. This is an incredibly powerful technique for finding subtle edge cases you would never think to test. For example, a property for a list-sorting function might be: “for any list of integers, the output should be sorted, and it should contain the same elements as the input.” Hypothesis would then generate empty lists, lists with one element, lists with duplicates, lists with large numbers, and so on, to vigorously test that property. Staying updated with the latest in python news and libraries like Hypothesis is key to writing truly robust applications for critical systems.

Conclusion: Building a Culture of Quality

The advanced testing strategies we’ve covered—scoped fixtures, strategic mocking, Test-Driven Development, and parametrization—are more than just tools for finding bugs. They are disciplines that foster better software design, improve maintainability, and build developer confidence. Fixtures provide clean, reusable, and performant test setups. Mocking gives you the power to isolate and test complex units of code without their external dependencies. TDD provides a structured workflow that ensures your code is testable and correct from the very beginning.

By integrating these techniques into your development process, you shift testing from an afterthought to a core part of your workflow. The result is a robust, self-testing codebase that serves as a solid foundation, enabling you to add features and refactor with the assurance that your automated test suite has your back.