Deep Dive into Modern Malware Analysis: Techniques, Python Automation, and Reverse Engineering

Malware analysis is the art of dissecting malicious software to understand its behavior, origin, and potential impact. In an era where threat actors utilize sophisticated command-and-control (C2) frameworks and polymorphic code, the role of the security researcher has evolved from manual debugging to building complex, automated analysis pipelines. While the target malware is often written in C, C++, or Go, the lingua franca of the modern analyst is undoubtedly Python. This article explores the depths of malware analysis, ranging from static examination to advanced dynamic behavior monitoring, while highlighting how the modern Python ecosystem supports these critical security workflows.

The landscape of cybersecurity is shifting rapidly. We are seeing a move towards Python security integration, where tools must be as robust as the threats they analyze. With the advent of Local LLM integration for log parsing and Edge AI for on-device detection, the barrier to entry for analysis is lowering, but the ceiling for expertise is rising. Whether you are investigating a financial trojan targeting Python finance sectors or analyzing botnets via Python automation, understanding the core methodologies is essential.

Section 1: Static Analysis and File Internals

Static analysis involves examining the malware without executing it. This is the first line of defense and often yields Indicators of Compromise (IOCs) such as hardcoded IP addresses, mutexes, or cryptographic keys. The Portable Executable (PE) header is the most critical structure to analyze in Windows malware. It contains information about the code, data, imports, and exports.

Parsing PE Headers with Python

One of the most reliable libraries for this is pefile. By analyzing the Import Address Table (IAT), an analyst can guess the functionality of the binary. For instance, importing InternetOpenUrl suggests network activity, while WriteProcessMemory suggests code injection.

To maintain code quality in your analysis tools, it is highly recommended to use Type hints and validate your scripts with MyPy updates. Furthermore, integrating the Ruff linter or Black formatter ensures your analysis scripts remain readable and maintainable across large teams.

Here is a practical example of extracting imports and checking for suspicious sections using Python:

import pefile

import hashlib

from typing import List, Dict

def analyze_pe_structure(file_path: str) -> Dict[str, any]:

"""

Analyzes a PE file to extract imports and calculate section entropy.

High entropy often indicates packed or encrypted code.

"""

try:

pe = pefile.PE(file_path)

except FileNotFoundError:

return {"error": "File not found"}

analysis_result = {

"imports": {},

"sections": []

}

# Extract Imports

if hasattr(pe, 'DIRECTORY_ENTRY_IMPORT'):

for entry in pe.DIRECTORY_ENTRY_IMPORT:

dll_name = entry.dll.decode('utf-8')

functions = []

for func in entry.imports:

if func.name:

functions.append(func.name.decode('utf-8'))

analysis_result["imports"][dll_name] = functions

# Analyze Sections for Entropy (Packing Detection)

for section in pe.sections:

section_name = section.Name.decode('utf-8').strip('\x00')

entropy = section.get_entropy()

analysis_result["sections"].append({

"name": section_name,

"entropy": entropy,

"suspicious": entropy > 7.0 # Threshold for packed code

})

return analysis_result

# Example Usage

if __name__ == "__main__":

# In a real scenario, replace with a malware sample path

report = analyze_pe_structure("suspicious_sample.exe")

print(f"Detected {len(report.get('imports', {}))} imported DLLs.")

for sec in report.get("sections", []):

if sec["suspicious"]:

print(f"WARNING: Section {sec['name']} has high entropy ({sec['entropy']:.2f}). Likely packed.")In the code above, we calculate entropy. Malware authors often compress or encrypt their malicious payloads (packers), resulting in high entropy. If you are building a dashboard to visualize this data, modern libraries like Polars dataframe can handle millions of file artifacts faster than traditional methods, or you could visualize the results using Marimo notebooks for an interactive research experience.

Section 2: Dynamic Analysis and Automation

Dynamic analysis involves running the malware in a controlled environment (sandbox) to observe its behavior. This includes monitoring file system changes, registry modifications, and network traffic. However, modern malware is “sandbox-aware” and may cease execution if it detects it is being watched.

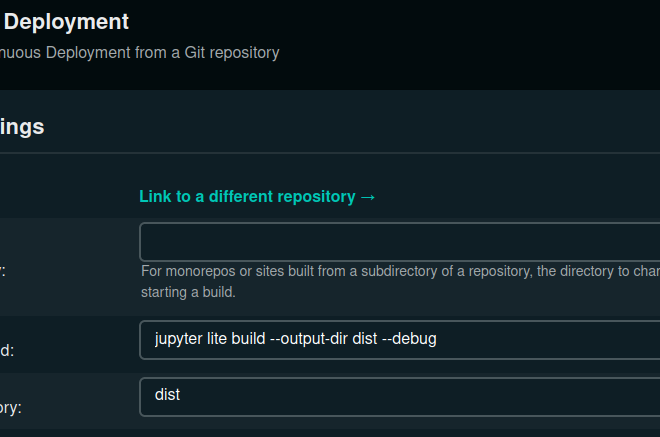

Automating the Sandbox

Automation is key. Using tools like Playwright python or Selenium news updates allows analysts to automate interaction with malicious URLs or downloaders that require user input (like CAPTCHAs) before triggering the payload. Furthermore, managing the Python environment for these automation tools has become easier with the Uv installer, Rye manager, or PDM manager, ensuring reproducible analysis environments.

When analyzing network traffic (PCAP), we often look for “beacons” or callbacks to C2 servers. Below is a script that simulates a basic network sniffer and parser, which could be enhanced with Scrapy updates if crawling the destination infrastructure.

import re

import json

from datetime import datetime

class NetworkBehaviorAnalyzer:

def __init__(self, log_file: str):

self.log_file = log_file

self.suspicious_patterns = [

r"api\.telegram\.org", # Common C2 channel

r"discord\.com\/api", # Common C2 channel

r"\.bit$", # Namecoin domains

r"raw\.githubusercontent\.com" # Staging payload source

]

def parse_logs(self):

"""

Simulates parsing network logs (e.g., Zeek or Suricata output)

looking for IOCs.

"""

detected_threats = []

# Simulating reading a large log file

# In production, consider using 'Polars dataframe' for performance

try:

with open(self.log_file, 'r') as f:

for line in f:

for pattern in self.suspicious_patterns:

if re.search(pattern, line, re.IGNORECASE):

detected_threats.append({

"timestamp": datetime.now().isoformat(),

"indicator": pattern,

"raw_log": line.strip()

})

except FileNotFoundError:

print("Log file not found.")

return detected_threats

# Mocking a log file creation for demonstration

with open("network_traffic.log", "w") as f:

f.write("GET http://malicious-site.bit/payload.bin HTTP/1.1\n")

f.write("POST https://api.telegram.org/bot12345/sendMessage HTTP/1.1\n")

analyzer = NetworkBehaviorAnalyzer("network_traffic.log")

alerts = analyzer.parse_logs()

print(json.dumps(alerts, indent=2))For more advanced dynamic analysis, researchers are now looking into LangChain updates and LlamaIndex news to ingest massive amounts of sandbox logs and query them using natural language (e.g., “Show me all registry keys created that persist after reboot”). This integration of Local LLM technology ensures data privacy while accelerating the “Time to Verdict.”

Section 3: Advanced Deobfuscation and Reverse Engineering

Malware authors use obfuscation to hide their intent. This often involves XOR encoding, Base64 strings, or custom encryption routines. Advanced analysis often requires writing decoders or emulating specific CPU instructions.

Performance in Emulation

Emulating code (using tools like Qiling or Unicorn) is CPU-intensive. This is where recent Python advancements become relevant. The discussions around GIL removal and Free threading in Python 3.13+ are promising for malware emulators, allowing them to utilize multi-core processors more effectively. Additionally, the emergence of Rust Python and the Mojo language offers paths to write high-performance analysis modules that interface seamlessly with Python.

Below is an example of a simple deobfuscator that attempts to brute-force a single-byte XOR key, a common technique in malware config extraction.

def xor_decrypt(data: bytes, key: int) -> bytes:

return bytes([b ^ key for b in data])

def brute_force_xor(encrypted_payload: bytes, known_header: bytes):

"""

Attempts to find the XOR key by matching a known file header

(e.g., 'MZ' for executables or specific magic bytes).

"""

print(f"Attempting to decrypt {len(encrypted_payload)} bytes...")

possible_keys = []

# Iterate through all possible byte keys (0-255)

for key in range(256):

decrypted = xor_decrypt(encrypted_payload, key)

# Check if the decrypted data starts with the known header

if decrypted.startswith(known_header):

print(f"[+] Found potential key: {hex(key)}")

possible_keys.append((key, decrypted[:50])) # Show preview

return possible_keys

# Example: A generic shellcode or config might be XORed

# 'MZ' header is 0x4D 0x5A. Let's say the key is 0xAA.

# 0x4D ^ 0xAA = 0xE7, 0x5A ^ 0xAA = 0xF0

dummy_encrypted = b'\xE7\xF0\x99\x88\xAA' # Mock encrypted data

results = brute_force_xor(dummy_encrypted, b'MZ')

if not results:

print("[-] No valid key found.")For more complex algorithmic obfuscation, analysts might turn to PyTorch news or Scikit-learn updates to train models that recognize obfuscated code blocks versus legitimate code. The intersection of Algo trading logic (pattern recognition in time series) and malware beaconing detection is also a growing field.

Section 4: Building the Analysis Lab and Best Practices

Building a malware lab requires a robust software stack. You aren’t just writing scripts; you are building applications. Frameworks like FastAPI news or Litestar framework are excellent for building internal APIs that process malware samples. For the frontend, tools like Reflex app, Flet ui, or Taipy news allow Python developers to create interactive dashboards without needing extensive JavaScript knowledge.

Security and Environment Management

When installing libraries to analyze malware, supply chain security is paramount. Always be aware of PyPI safety. Using modern build tools like Hatch build ensures your environment is isolated. Additionally, if you are analyzing IoT malware, keeping up with MicroPython updates and CircuitPython news is vital, as malware targeting embedded devices often utilizes these lightweight runtimes.

Here is a snippet demonstrating how to structure a robust analysis class using modern Python features like data classes and logging, which is essential when processing thousands of samples.

from dataclasses import dataclass, field

from datetime import datetime

import logging

# Configure logging to track analysis steps

logging.basicConfig(level=logging.INFO, format='%(asctime)s - %(levelname)s - %(message)s')

@dataclass

class MalwareSample:

file_hash: str

file_size: int

discovery_date: datetime = field(default_factory=datetime.now)

tags: list[str] = field(default_factory=list)

def add_tag(self, tag: str):

if tag not in self.tags:

self.tags.append(tag)

logging.info(f"Tag '{tag}' added to sample {self.file_hash[:8]}...")

def generate_report(self):

# Placeholder for report generation logic

# Could integrate with 'DuckDB python' for storing results

return {

"id": self.file_hash,

"meta": {

"size": self.file_size,

"timestamp": self.discovery_date.isoformat()

},

"classification": self.tags

}

# Usage

sample = MalwareSample(file_hash="a1b2c3d4e5...", file_size=102400)

sample.add_tag("Ransomware")

sample.add_tag("BruteRatel_Variant") # Hypothetical tag

print(sample.generate_report())Conclusion

Malware analysis is a discipline that requires a constant thirst for knowledge. As threat actors evolve, utilizing languages like Rust and Go, or employing quantum-resistant encryption (necessitating awareness of Qiskit news and Python quantum developments), analysts must adapt. The integration of Python JIT compilers and Free threading will likely revolutionize how fast we can emulate and analyze threats.

From using Pandas updates and NumPy news for statistical analysis of binary entropy, to leveraging PyScript web for browser-based analysis tools, the ecosystem is vast. By mastering both the low-level details of assembly and PE headers, and the high-level capabilities of modern Python automation, you can produce comprehensive reports that not only describe what the malware does but also how to defend against it. Start small, automate often, and always keep your tools updated with tools like SonarLint python to ensure your analysis code is as secure as the systems you protect.