Stop Renting Cloud Computers: Building a Data Stack on Localhost

I looked at my AWS bill last month and laughed. Not the happy kind of laugh. The kind that sounds a bit like a sob. I was paying nearly $400 a month to process a dataset that—if I’m being completely honest—could fit on a thumb drive from 2015.

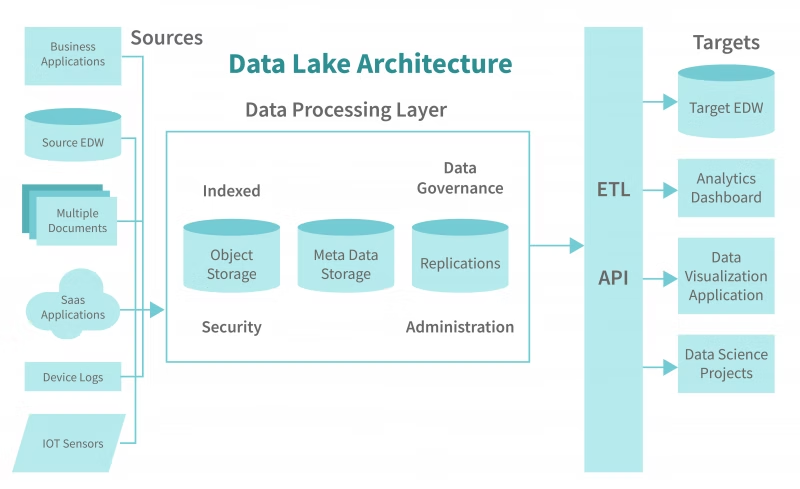

We’ve all been there. You start a project and immediately reach for the “industry standard” tools. You need ingestion? Spin up Kinesis or Flink. You need ETL? Write some Glue jobs. Warehousing? Redshift or Snowflake. Before you know it, you’re managing IAM roles, VPC endpoints, and security groups just to count how many users clicked a button on Tuesday.

It’s overkill. It’s exhausting. And frankly, it’s slow. Not the processing speed—the development speed. Waiting for a Glue job to spin up takes longer than the actual data processing.

So, last weekend, I killed the cloud infrastructure. I replaced the whole sprawling mess with a single Python script and DuckDB. The result? A pipeline that mimics the architecture of a massive distributed system—streaming ingest, partitioned storage, SQL analytics—running entirely on my MacBook. And it costs zero dollars.

The “Micro-Batch” Ingest (Goodbye, Flink)

In the big data world, we obsess over streaming frameworks. But locally? Python generators are your best friend (okay, I know I shouldn’t say “best friend,” but they really are). They let you handle infinite data streams without blowing up your RAM.

I needed to simulate an ingestion stream—raw JSON events coming in fast. Instead of setting up a Kafka broker, I just wrote a generator. It yields “micro-batches” of data. This keeps the memory footprint tiny, mimicking how Flink handles checkpoints.

Here’s the setup. It’s stupidly simple:

import duckdb

import pandas as pd

import time

import json

import random

from datetime import datetime

# Simulating a stream of raw messy data

def event_stream_generator(batch_size=10000):

while True:

batch = []

for _ in range(batch_size):

# Create some fake messy logs

event = {

'event_id': f"evt_{random.randint(1000, 999999)}",

'timestamp': datetime.now().isoformat(),

'user_data': json.dumps({

'id': random.randint(1, 100),

'action': random.choice(['click', 'view', 'purchase', 'error'])

}),

'latency_ms': random.gauss(100, 20)

}

batch.append(event)

# Yield a pandas DataFrame because DuckDB eats them alive

yield pd.DataFrame(batch)

time.sleep(0.1) # Simulate network latency

# Initialize our connection

con = duckdb.connect(database=':memory:') # We'll write to disk laterSee? No Zookeeper. No JVM tuning. Just a function that spits out data.

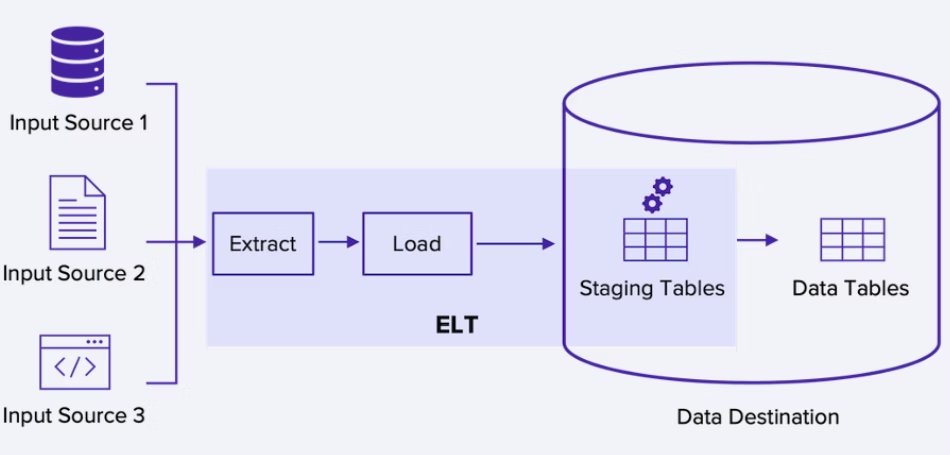

The ETL Layer (Goodbye, Glue)

AWS Glue is great if you have petabytes. For gigabytes? It’s like using a flamethrower to light a candle. DuckDB is the lighter.

The magic here is using DuckDB’s relational engine to clean up the messy JSON blobs from our “stream.” I wanted to extract fields, fix types, and then write the data out to partitioned Parquet files. This is exactly what a data lakehouse does, just without the marketing buzzwords.

I ran into a snag at first—I tried to process everything in a loop and append to a single file. Bad idea. Concurrency issues everywhere. The fix was to treat each batch as an atomic unit and write it to a hive-partitioned structure.

def process_batch(batch_df, batch_id):

# Register the dataframe as a virtual table

con.register('raw_batch', batch_df)

# Use SQL to clean, parse JSON, and derive columns

# This mimics the "Transform" in ETL

query = """

SELECT

event_id,

strptime(timestamp, '%Y-%m-%dT%H:%M:%S.%f') as event_time,

json_extract_string(user_data, '$.action') as action,

CAST(json_extract(user_data, '$.id') AS INTEGER) as user_id,

CAST(latency_ms AS INTEGER) as latency,

-- Create a partition key based on the minute

strftime(strptime(timestamp, '%Y-%m-%dT%H:%M:%S.%f'), '%Y%m%d_%H%M') as partition_key

FROM raw_batch

WHERE latency > 0 -- Basic data quality check

"""

# Execute the transformation

# COPY to Parquet with Hive partitioning

# This creates a folder structure: data/partition_key=20251229_1000/file.parquet

con.sql(f"""

COPY ({query})

TO 'local_datalake'

(FORMAT PARQUET, PARTITION_BY (partition_key), OVERWRITE_OR_IGNORE 1, FILENAME_PATTERN 'batch_{batch_id}_{{i}}')

""")

print(f"Batch {batch_id} processed and written to Parquet.")

# Run the pipeline for a few batches

stream = event_stream_generator(batch_size=5000)

for i in range(5):

batch_df = next(stream)

process_batch(batch_df, i)This part is satisfying. You watch the terminal update, and if you check your file system, you see this beautiful directory tree growing:

local_datalake/

├── partition_key=20251229_1420/

│ ├── batch_0_0.parquet

│ └── batch_1_0.parquet

├── partition_key=20251229_1421/

│ └── ...That’s a production-grade data lake layout. On your hard drive. Readable by anything—Spark, Presto, Pandas, whatever.

The Analytics Layer (Goodbye, Redshift)

Now for the payoff. In the cloud, this is where you’d spin up a Redshift cluster, wait 15 minutes for it to provision, and then run a COPY command to load the data you just wrote to S3.

With DuckDB, the “Warehouse” is just the compute engine pointing at those Parquet files. Zero load time. Zero waiting. You query the files directly.

I remember the first time I realized I could use glob patterns (**/*.parquet) in SQL. It felt like cheating.

# The "Redshift" replacement

# We query the Hive-partitioned parquet files directly

print("\n--- ANALYTICS REPORT ---\n")

# DuckDB automatically discovers the Hive partitions (partition_key)

# No need to explicitly declare them

analytics_query = """

SELECT

action,

count(*) as count,

avg(latency) as avg_latency,

min(event_time) as first_seen,

max(event_time) as last_seen

FROM read_parquet('local_datalake/*/*.parquet', hive_partitioning=1)

GROUP BY action

ORDER BY count DESC

"""

results = con.sql(analytics_query).df()

print(results)

# Let's do something complex - a window function over the file set

print("\n--- USER SESSION ANALYSIS ---\n")

complex_query = """

SELECT

user_id,

action,

event_time,

event_time - LAG(event_time) OVER (PARTITION BY user_id ORDER BY event_time) as time_since_last_action

FROM read_parquet('local_datalake/*/*.parquet', hive_partitioning=1)

WHERE user_id = 42

ORDER BY event_time DESC

LIMIT 5

"""

print(con.sql(complex_query).df())Why This Matters

Look, I’m not saying you should run Netflix on a MacBook Air. If you have petabytes of data, go use the cloud. Pay the premium. It’s worth it for the scalability.

But for the rest of us? The data scientists working on 50GB datasets? The engineers prototyping a new feature? We’ve been gaslit into thinking we need “Big Data” infrastructure for small data problems.

This script runs instantly. It costs nothing. It’s easy to debug because you can step through it in VS Code. If it crashes, you don’t have orphaned resources billing you by the hour.

The best part? If you do eventually need to move to the cloud, the logic is identical. You just swap the local file paths for S3 buckets (s3://my-bucket/) and DuckDB handles the rest seamlessly. Wait, I promised myself I wouldn’t use that word. It handles it easily.

So next time you’re about to write Terraform scripts for a simple ETL job, stop. Open a Python file. Import DuckDB. You might just finish the project before the cloud resources would have finished provisioning.