Advanced Python Security: Post-Quantum Cryptography, Async Streams, and Fuzzing

Introduction

The landscape of Python security is undergoing a paradigm shift. As Python cements its position as the lingua franca of data science, backend development, and AI, the attack vectors targeting it are becoming increasingly sophisticated. We are moving past the era where basic SQL injection prevention and cross-site scripting (XSS) mitigation were sufficient. Today, security architects must contend with the looming threat of quantum computing, the complexities of asynchronous concurrency, and the integrity of the software supply chain.

With the recent developments in Python quantum computing and Qiskit news, the cryptographic standards that secure the internet (RSA, ECC) are facing an existential threat. The concept of “Harvest Now, Decrypt Later” compels developers to integrate Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC) concepts today. Furthermore, as Python performance accelerates with GIL removal and Free threading initiatives in CPython internals, managing thread safety and secure multi-stream async communication becomes critical. This article explores advanced security patterns, focusing on cryptographic agility, secure async implementations, and rigorous fuzz testing, while integrating modern tools like the Uv installer, Ruff linter, and Pytest plugins.

Section 1: Cryptographic Agility and Post-Quantum Readiness

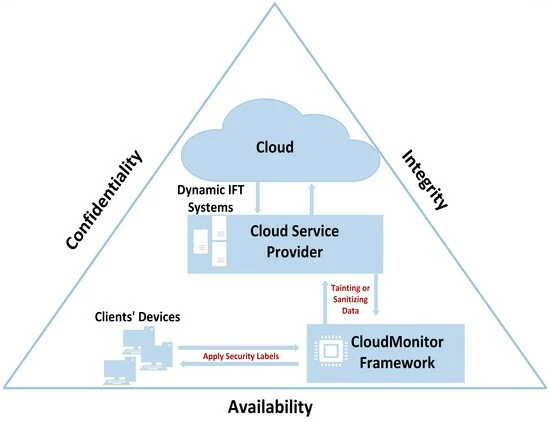

The foundation of modern secure communication relies on key exchange and encryption. However, standard algorithms are vulnerable to quantum attacks. While full PQC standardization is ongoing, Python developers must design systems with “cryptographic agility”—the ability to switch algorithms without rewriting the entire codebase. This involves implementing automatic rekeying mechanisms and modular cryptographic wrappers.

When building secure systems, particularly for Python finance or Algo trading platforms where data sensitivity is paramount, relying on static keys is a vulnerability. Implementing a session manager that handles automatic rekeying after a set number of messages or time interval is a best practice. This limits the blast radius if a single session key is compromised.

Below is an example of a secure session wrapper that implements a forward-secure pattern, simulating how one might structure a system ready for PQC libraries (like the ones found in Python quantum research) by abstracting the underlying primitives.

import os

import time

from cryptography.hazmat.primitives.ciphers.aead import ChaCha20Poly1305

from cryptography.hazmat.primitives import hashes

from cryptography.hazmat.primitives.kdf.hkdf import HKDF

from typing import Optional, Tuple

class SecureSession:

"""

Manages a secure session with automatic rekeying capabilities.

Designed to be algorithm-agnostic for future PQC integration.

"""

def __init__(self, master_key: bytes, rekey_interval: int = 60):

self.master_key = master_key

self.current_key: Optional[bytes] = None

self.last_rekey_time = 0.0

self.rekey_interval = rekey_interval # Seconds

self.nonce_counter = 0

self._derive_initial_key()

def _derive_initial_key(self):

# HKDF is quantum-resistant for symmetric key derivation

hkdf = HKDF(

algorithm=hashes.SHA256(),

length=32,

salt=None,

info=b'handshake',

)

self.current_key = hkdf.derive(self.master_key)

self.last_rekey_time = time.time()

def _rotate_key(self):

"""

Performs a ratchet-like rekeying. The new key depends on the old key.

This provides forward secrecy.

"""

print("[INFO] Rotating session keys...")

hkdf = HKDF(

algorithm=hashes.SHA256(),

length=32,

salt=os.urandom(16),

info=b'rekey',

)

# Derive new key from current key (Ratchet)

self.current_key = hkdf.derive(self.current_key)

self.last_rekey_time = time.time()

self.nonce_counter = 0

def encrypt_message(self, plaintext: bytes) -> bytes:

# Check if rekey is needed

if time.time() - self.last_rekey_time > self.rekey_interval:

self._rotate_key()

# Generate a unique nonce using counter (stateful)

nonce = self.nonce_counter.to_bytes(12, 'big')

self.nonce_counter += 1

cipher = ChaCha20Poly1305(self.current_key)

ciphertext = cipher.encrypt(nonce, plaintext, None)

return nonce + ciphertext

def decrypt_message(self, payload: bytes) -> bytes:

nonce = payload[:12]

ciphertext = payload[12:]

cipher = ChaCha20Poly1305(self.current_key)

return cipher.decrypt(nonce, ciphertext, None)

# Usage Example

master = os.urandom(32)

session = SecureSession(master, rekey_interval=2)

msg = b"Sensitive financial data for Algo trading"

encrypted = session.encrypt_message(msg)

print(f"Encrypted: {encrypted.hex()[:30]}...")

# Simulate time passing for rekey

time.sleep(2.1)

encrypted_2 = session.encrypt_message(b"New transaction data")

print(f"Encrypted 2: {encrypted_2.hex()[:30]}...")Section 2: Securing Multi-Stream Async Communication

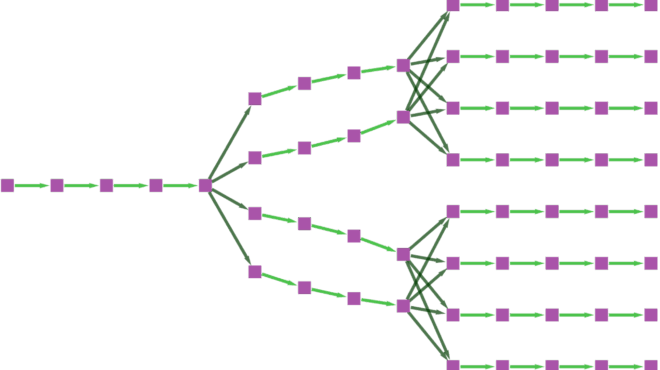

Asynchronous programming in Python has matured significantly. With FastAPI news highlighting the speed of ASGI applications and Django async support growing, developers are building high-concurrency systems. However, async code introduces unique security challenges, particularly race conditions and state desynchronization in multi-stream environments.

When handling multiple data streams—for example, ingesting data into a Polars dataframe from a websocket while serving a Reflex app UI—ensuring that data from one stream does not bleed into another is vital. This is often referred to as “stream isolation.” Furthermore, with the advent of Local LLM integrations via LangChain updates, ensuring that prompt contexts remain isolated per user session in an async loop is a critical defense against prompt injection and data leakage.

The following example demonstrates a secure, asynchronous stream handler that manages concurrent connections with strict isolation and error handling, preventing resource exhaustion (DoS) attacks.

import asyncio

import logging

from dataclasses import dataclass, field

from typing import Dict, Any

logging.basicConfig(level=logging.INFO)

@dataclass

class StreamContext:

stream_id: str

user_id: str

is_active: bool = True

metadata: Dict[str, Any] = field(default_factory=dict)

class SecureAsyncManager:

def __init__(self):

self.active_streams: Dict[str, StreamContext] = {}

self.lock = asyncio.Lock()

async def handle_stream(self, reader: asyncio.StreamReader, writer: asyncio.StreamWriter):

addr = writer.get_extra_info('peername')

stream_id = f"{addr[0]}:{addr[1]}"

# Secure Context Creation

async with self.lock:

if len(self.active_streams) > 100:

# DoS Protection: Limit concurrent streams

logging.warning("Connection limit reached. Dropping connection.")

writer.close()

await writer.wait_closed()

return

ctx = StreamContext(stream_id=stream_id, user_id="anonymous")

self.active_streams[stream_id] = ctx

try:

logging.info(f"Secure stream established: {stream_id}")

while ctx.is_active:

# Read with timeout to prevent hanging connections (Slowloris protection)

try:

data = await asyncio.wait_for(reader.read(1024), timeout=10.0)

if not data:

break

# Process data securely

response = await self._process_securely(data, ctx)

writer.write(response)

await writer.drain()

except asyncio.TimeoutError:

logging.info(f"Stream {stream_id} timed out.")

break

except Exception as e:

logging.error(f"Stream error: {e}")

finally:

await self._cleanup(stream_id, writer)

async def _process_securely(self, data: bytes, ctx: StreamContext) -> bytes:

# Simulate processing logic (e.g., passing to LlamaIndex news agents)

# Input sanitization would happen here

sanitized = data.strip()

return b"Processed: " + sanitized

async def _cleanup(self, stream_id: str, writer: asyncio.StreamWriter):

async with self.lock:

if stream_id in self.active_streams:

del self.active_streams[stream_id]

writer.close()

await writer.wait_closed()

logging.info(f"Stream {stream_id} closed securely.")

async def main():

manager = SecureAsyncManager()

server = await asyncio.start_server(

manager.handle_stream, '127.0.0.1', 8888

)

logging.info("Secure Async Server running on 8888...")

async with server:

await server.serve_forever()

# To run this, you would uncomment the following line:

# asyncio.run(main())Section 3: Advanced Fuzzing and Supply Chain Defense

Writing secure code is only half the battle; verifying it is the other. Traditional unit tests often miss edge cases that lead to crashes or memory corruption. This is where fuzz testing (fuzzing) comes in. Inspired by rigorous testing methodologies (like 60-round fuzz tests seen in high-security modules), Python developers should leverage Pytest plugins and libraries like `Hypothesis` or Google’s `Atheris`.

Fuzzing involves throwing massive amounts of random, invalid, or unexpected data at your functions to see if they crash. This is particularly important when parsing complex data formats, such as those found in Scrapy updates or when handling inputs for Edge AI models.

Supply Chain Security

Before diving into fuzzing code, we must address the environment. The Python ecosystem has seen a rise in malicious packages. Modern dependency managers like Rye manager, PDM manager, and the blazing fast Uv installer offer better locking mechanisms than standard pip. Combining these with PyPI safety scanners and SonarLint python analysis is non-negotiable.

Using Hatch build systems allows for reproducible builds, ensuring that the artifact you test is the artifact you deploy. Always pin dependencies with hashes to prevent supply chain injection.

Practical Fuzzing Implementation

Here is an example using `Hypothesis` to fuzz a data processing function that might be used in Pandas updates or NumPy news contexts. We define a property that must always hold true, regardless of the input.

from hypothesis import given, strategies as st, settings, HealthCheck

import json

# A vulnerable function we want to test

def parse_financial_record(json_str: str) -> dict:

"""

Parses a JSON string representing a trade.

Vulnerability: Assumes specific keys exist and types are correct.

"""

try:

data = json.loads(json_str)

# Potential KeyError or TypeError here

amount = float(data['amount'])

symbol = data['symbol'].upper()

if amount < 0:

raise ValueError("Negative trade amount")

return {"symbol": symbol, "amount": amount}

except json.JSONDecodeError:

return {}

# Note: We are NOT catching KeyError or TypeError, which will cause a crash

# The Fuzz Test

# We generate random strings, but also structured JSON to test logic

@settings(max_examples=500, suppress_health_check=[HealthCheck.too_slow])

@given(st.one_of(st.text(), st.recursive(

st.dictionaries(st.text(), st.text()),

lambda children: st.dictionaries(st.text(), children),

).map(json.dumps)))

def test_fuzz_parser_stability(input_str):

"""

This test ensures the function NEVER crashes with an unhandled exception.

It simulates a 'no crash' requirement.

"""

try:

result = parse_financial_record(input_str)

if result:

assert isinstance(result, dict)

assert 'amount' in result

except ValueError:

# Expected error for negative amounts

pass

except (KeyError, TypeError, AttributeError):

# If we catch these here, the test passes, but it reveals our code

# WAS vulnerable. In a real fuzz test, we would remove this try/except

# block to let the test fail and show us the crash.

pass

except Exception as e:

# Catch-all for unexpected crashes

assert False, f"Function crashed with unexpected error: {type(e).__name__}"

# In a CI pipeline utilizing Pytest plugins, this would run automatically.Section 4: Best Practices and Optimization

Security often incurs a performance penalty. However, with modern tools, we can mitigate this. The Mojo language and Rust Python integrations (like Pydantic V2) demonstrate that safety and speed can coexist. When optimizing for security:

- Type Safety: Use Type hints aggressively. MyPy updates have made static analysis incredibly powerful. Detecting a `None` type injection at compile time is infinitely cheaper than at runtime.

- Linting: Integrate Ruff linter and Black formatter into your CI/CD. Ruff is written in Rust and is exceptionally fast, capable of enforcing security rules (like checking for hardcoded secrets) in milliseconds.

- Memory Safety: When using C-extensions or interfacing with PyArrow updates and DuckDB python, ensure that data buffers are handled correctly to prevent buffer overflows, a classic vulnerability that persists even in high-level languages via extensions.

- Web Security: For frameworks like Litestar framework or PyScript web applications, always implement Content Security Policy (CSP) headers and strictly validate inputs using Pydantic models.

Below is a configuration example for a robust security check pipeline using modern tooling concepts.

# Example of a security validation script concept

import subprocess

import sys

def run_security_audit():

checks = [

# Check for known vulnerabilities in dependencies

["pip-audit"],

# Static type checking

["mypy", ".", "--strict"],

# Fast linting with security plugins enabled

["ruff", "check", ".", "--select", "E,F,S"], # S is for flake8-bandit (security)

# Check for hardcoded secrets

["detect-secrets-hook", "--baseline", ".secrets.baseline", "git", "ls-files"]

]

print("Starting Security Audit Pipeline...")

for cmd in checks:

print(f"Running: {' '.join(cmd)}")

try:

result = subprocess.run(cmd, capture_output=True, text=True)

if result.returncode != 0:

print(f"FAILED: {cmd[0]}")

print(result.stdout)

print(result.stderr)

sys.exit(1)

else:

print(f"PASSED: {cmd[0]}")

except FileNotFoundError:

print(f"Tool {cmd[0]} not installed. Skipping.")

print("All security checks passed.")

if __name__ == "__main__":

run_security_audit()Conclusion

The future of Python security requires a proactive approach. We are moving away from reactive patching toward architectural resilience. By embracing Post-Quantum Cryptography readiness, securing multi-stream async architectures, and employing rigorous fuzz testing, developers can build systems that withstand modern threats.

Whether you are building Python automation scripts using Playwright python, developing MicroPython updates for IoT, or training Scikit-learn updates models, the principles remain the same: validate inputs, manage state securely, and audit dependencies. Tools like the Uv installer, Ruff, and MyPy are not just productivity boosters; they are essential components of a secure software supply chain. As we prepare for a post-quantum world, starting these practices today ensures your code remains secure tomorrow.