Unlocking Bacterial Metabolism: Deep Learning and Knowledge Graphs with the IBIS Framework

The landscape of bacterial genomics is undergoing a seismic shift. As sequencing technologies become cheaper and more accessible, the volume of genomic data is expanding at an exponential rate. However, our ability to interpret this data—specifically, to understand the complex metabolic machinery of bacteria—has lagged behind. Traditional bioinformatics tools, often reliant on Profile Hidden Markov Models (pHMMs) and homology-based alignment, are struggling to keep pace with the diversity and scale of newly sequenced microbiomes. Enter the IBIS framework (Integrated Bacterial Information System), a novel, unified approach that leverages deep learning, Transformers, and Knowledge Graphs (KGs) to annotate and compare bacterial metabolism at an unprecedented scale.

IBIS represents a paradigm shift from static database lookups to dynamic, embedding-based inference. By integrating protein sequence encoders, graph neural networks for gene clusters, and a massive knowledge graph connecting enzymes to ecological metadata, IBIS offers a comprehensive view of both primary and specialized metabolism. For data scientists and bioinformaticians, understanding the architecture of IBIS provides a masterclass in applying modern AI—comparable to advancements seen in Local LLM development and Edge AI—to biological questions.

In this article, we will explore the technical architecture of IBIS, dissect its core components like IBIS-Enzyme and IBIS-KG, and discuss how modern Python infrastructure supports such high-throughput frameworks. We will also touch upon how the broader Python ecosystem, from Polars dataframe optimizations to PyTorch news, intersects with computational biology.

Section 1: The Core Architecture – Transformers and Embeddings

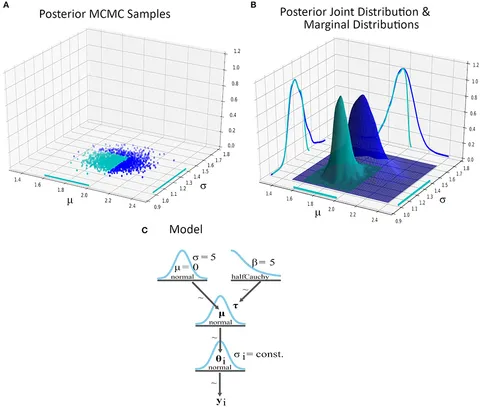

At the heart of the IBIS framework lies the concept of biological embeddings. Traditional tools like DIAMOND or HMMER rely on direct sequence alignment, which can be computationally expensive and less sensitive to remote homology. IBIS adopts a “sequence-as-language” approach, utilizing Transformer models to encode protein sequences into dense vector representations. This is similar to how Large Language Models (LLMs) process text, a domain currently buzzing with LangChain updates and LlamaIndex news.

IBIS-Enzyme: Protein Language Modeling

IBIS-Enzyme utilizes a Transformer architecture to predict enzyme classes with remarkable accuracy (F1 scores reaching 0.95). Unlike tools that require manual feature engineering, IBIS-Enzyme learns the “grammar” of amino acids. By encoding sequences into embeddings, the model can generalize to untrained Enzyme Commission (EC) numbers, outperforming established tools like DeepEC and CLEAN.

This embedding-based approach allows for vector-based lookups, which are orders of magnitude faster than alignment. In a production environment, this speed is critical. It mirrors the performance gains developers seek when exploring GIL removal and Free threading in the upcoming Python versions, aiming to maximize throughput on multi-core systems.

Below is a conceptual example of how one might implement a protein sequence encoder using PyTorch, similar to the architecture used in IBIS-Enzyme:

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

from transformers import BertModel, BertTokenizer

class ProteinEncoder(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, model_name='Rostlab/prot_bert', output_dim=128):

super(ProteinEncoder, self).__init__()

# Utilizing a pre-trained Protein BERT model

self.bert = BertModel.from_pretrained(model_name)

# Projection layer to create compact embeddings for the Knowledge Graph

self.projection = nn.Linear(1024, output_dim)

self.dropout = nn.Dropout(0.1)

def forward(self, input_ids, attention_mask):

outputs = self.bert(input_ids=input_ids, attention_mask=attention_mask)

# Use the CLS token representation

cls_token = outputs.last_hidden_state[:, 0, :]

embedding = self.projection(self.dropout(cls_token))

return embedding

# Example Usage

tokenizer = BertTokenizer.from_pretrained('Rostlab/prot_bert', do_lower_case=False)

sequence = "MKTLLILAVSLIAAGLSGC" # Sample protein sequence

inputs = tokenizer(sequence, return_tensors="pt")

model = ProteinEncoder()

with torch.no_grad():

vector_embedding = model(inputs['input_ids'], inputs['attention_mask'])

print(f"Generated Embedding Shape: {vector_embedding.shape}")

# Output: Generated Embedding Shape: torch.Size([1, 128])Domain-Level Annotation

Beyond whole proteins, IBIS-Domain drills down into specific functional units. This is particularly useful for biosynthetic enzymes like Non-Ribosomal Peptide Synthetases (NRPS) and Polyketide Synthases (PKS). By predicting substrate specificity with higher accuracy than prior tools, IBIS facilitates the discovery of novel chemotypes. This granular analysis requires rigorous data validation, much like using Pydantic or Type hints with MyPy updates to ensure data integrity in complex Python pipelines.

Section 2: Graph Neural Networks for Biosynthetic Gene Clusters

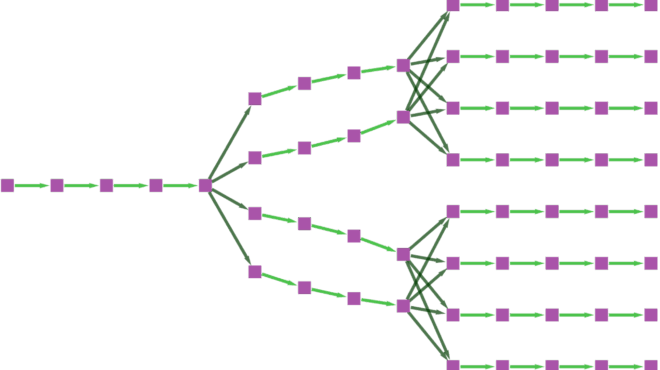

While enzymes are the workers, Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs) are the factories. Identifying these clusters is traditionally done using rule-based detection (e.g., antiSMASH). IBIS-SM introduces a Graphormer model—a graph transformer—to identify BGCs without relying on pHMMs. This allows for superior boundary calling and chemotype classification across dozens of classes.

Structure-Aware Clustering with IBIS-BGC

One of the most impressive feats of the framework is IBIS-BGC, which generates vector embeddings for entire BGCs. This enables the clustering of nearly 2 million BGCs into families in under an hour. To put this in perspective, previous methods like BiG-SLiCE could take days to process similar datasets. This leap in performance is akin to the speed improvements seen when switching from standard Pandas to Polars dataframe or utilizing DuckDB python for analytical queries on large datasets.

The graph representation captures the genomic context—the order and orientation of genes—which is crucial for function. Here is how one might structure genomic data for a Graph Neural Network (GNN) input using standard libraries:

import torch

from torch_geometric.data import Data

def create_bgc_graph(genes, edges):

"""

genes: List of gene feature vectors (node features)

edges: Adjacency list representing genomic proximity (edge index)

"""

# Convert features to tensors

x = torch.tensor(genes, dtype=torch.float)

edge_index = torch.tensor(edges, dtype=torch.long)

# Create PyG Data object

graph_data = Data(x=x, edge_index=edge_index.t().contiguous())

return graph_data

# Mock data: 3 genes in a cluster, connected linearly

gene_features = [

[0.1, 0.9, 0.5], # Gene A features (e.g., enzyme class probabilities)

[0.8, 0.1, 0.2], # Gene B

[0.4, 0.4, 0.4] # Gene C

]

# Edges: A-B, B-C

genomic_edges = [[0, 1], [1, 2]]

bgc_graph = create_bgc_graph(gene_features, genomic_edges)

print(f"Graph Nodes: {bgc_graph.num_nodes}")

print(f"Graph Edges: {bgc_graph.num_edges}")

# This graph object is now ready for a Graphormer modelSection 3: The Knowledge Graph (IBIS-KG) and Discovery

The true power of IBIS is realized in IBIS-KG. This module connects enzyme annotations with ecological and taxonomic metadata. By structuring data as a Knowledge Graph, researchers can query relationships that were previously invisible. For instance, IBIS-KG can reveal that specific uncharacterized enzymes are statistically enriched in certain ecological niches, such as marine sediments or plant roots.

This approach has led to the identification of over 100,000 genomic regions enriched with uncharacterized enzymes. The ability to query this vast network allows for “guilt-by-association” discovery, a technique that shares conceptual similarities with recommendation algorithms used in Python finance and Algo trading strategies, where hidden patterns in data streams signal opportunities.

Handling Data at Scale

Managing the outputs of IBIS-KG requires robust data engineering. The sheer volume of connections necessitates tools that handle out-of-core processing. While the bioinformatics tool is named IBIS, data engineers might be reminded of the Ibis framework for Python—a portable dataframe library that decouples the API from the execution engine. Using tools like Ibis (the data tool) or PyArrow updates allows bioinformaticians to query these massive genomic datasets efficiently without loading everything into RAM.

Here is an example of how one might query the results of an IBIS run using a modern dataframe approach to filter for high-confidence, uncharacterized enzymes:

import polars as pl

def filter_novel_candidates(results_path, confidence_threshold=0.9):

# Using Polars for high-performance lazy evaluation

# This is crucial when dealing with millions of annotations

q = (

pl.scan_csv(results_path)

.filter(pl.col("is_characterized") == False)

.filter(pl.col("prediction_confidence") > confidence_threshold)

.filter(pl.col("niche_association").is_not_null())

.select([

"protein_id",

"predicted_class",

"niche_association",

"genome_source"

])

)

# Execute the query

candidates = q.collect()

return candidates

# In a real scenario, this allows filtering 2M+ rows in sub-seconds

# contrasting with slower legacy methods.

# df = filter_novel_candidates("ibis_output_large.csv")Section 4: Implementation and Best Practices

Deploying a framework as complex as IBIS requires a modern, secure, and efficient Python environment. The days of managing dependencies with a simple requirements.txt are fading in favor of more robust tools.

Modern Dependency Management

To run IBIS and its dependencies (PyTorch, Transformers, NetworkX), it is highly recommended to use modern package managers. The Uv installer has gained traction for its incredible speed, while the Rye manager offers a comprehensive project management experience. Alternatively, PDM manager and Hatch build systems provide excellent isolation, ensuring that the complex dependency trees of bioinformatics tools do not conflict.

Performance and Security

When processing genomic data, especially from public repositories, Python security is paramount. Input validation is critical to prevent malformed files from crashing the pipeline. Tools like Ruff linter and Black formatter should be integrated into the development workflow to maintain code quality. Furthermore, static analysis with SonarLint python can help catch potential vulnerabilities early.

For those looking to expose IBIS functionality via a web interface—perhaps to allow other researchers to query the Knowledge Graph—modern web frameworks are essential. FastAPI news frequently highlights performance gains that make it the go-to choice, though the Litestar framework and Django async capabilities are strong contenders. For building rapid internal dashboards, Reflex app, Flet ui, or Taipy news offer Python-only frontend development, bypassing the need for React or Vue.

Here is a snippet showing how to serve an IBIS prediction model using FastAPI, incorporating type hints for validation:

from fastapi import FastAPI, HTTPException

from pydantic import BaseModel, Field

from typing import List

app = FastAPI(title="IBIS-Enzyme API")

class SequenceInput(BaseModel):

id: str

sequence: str = Field(..., min_length=10, description="Protein amino acid sequence")

class PredictionOutput(BaseModel):

enzyme_class: str

confidence: float

@app.post("/predict", response_model=PredictionOutput)

async def predict_enzyme(input_data: SequenceInput):

# Simulate model inference

# In production, this would call the loaded IBIS-Enzyme model

# Basic validation logic

valid_chars = set("ACDEFGHIKLMNPQRSTVWY")

if not set(input_data.sequence.upper()).issubset(valid_chars):

raise HTTPException(status_code=400, detail="Invalid amino acid characters detected")

return PredictionOutput(

enzyme_class="EC 1.14.13",

confidence=0.98

)

# Run with: uvicorn main:app --reloadFuture Directions and Conclusion

The IBIS framework represents a significant leap forward in our ability to decode bacterial metabolism. By combining Deep Learning with Knowledge Graphs, it illuminates the “dark matter” of the microbial world—the 6–25% of enzymes that remain unassigned. This has profound implications for drug discovery, as validated by the isolation of novel xenoamicin and amicoumacin analogs.

Looking ahead, the integration of such frameworks with emerging technologies is exciting. We might see Mojo language being used to rewrite performance-critical bottlenecks in bioinformatics pipelines, offering C-level speed with Python syntax. Python quantum computing libraries like Qiskit news suggests could eventually aid in simulating complex enzymatic reactions that are currently intractable.

Furthermore, as we push sequencing to the field, MicroPython updates and CircuitPython news may enable lightweight versions of these models to run on portable sequencing devices. Whether you are interested in Scikit-learn updates for improving classification or Playwright python for scraping metadata to enrich Knowledge Graphs, the convergence of modern software engineering and biology is creating a golden age for discovery.

IBIS is not just a tool; it is a blueprint for the future of high-throughput genomic annotation—scalable, interpretable, and deeply integrated with the vast ecosystem of AI and data science.