Unlocking True Parallelism: A Deep Dive into GIL Removal and Python’s Free-Threading Future

For decades, the Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) has been the single most controversial feature within CPython internals. It is the mechanism that ensures only one thread executes Python bytecode at a time, effectively preventing true parallelism on multi-core processors. While this design simplified memory management and made integration with C libraries easier in the 1990s, it has become a significant bottleneck in an era dominated by multi-core architectures and high-performance computing needs.

However, the landscape is shifting dramatically. With the introduction of Python 3.13, the community is witnessing the experimental rollout of GIL removal, also known as “free threading” (PEP 703). This is not merely an incremental update; it is a fundamental architectural overhaul that promises to reshape how we approach Python automation, Edge AI, and scientific computing. While the Mojo language and Rust Python implementations have challenged Python’s dominance by offering superior performance, the core CPython team is striking back.

In this comprehensive guide, we will explore the technical implications of free threading, how it compares to existing concurrency models, and how the modern ecosystem—from Polars dataframe to LangChain updates—is adapting to a parallel future.

The Concurrency Conundrum: Why the GIL Matters

To understand the magnitude of GIL removal, we must first analyze the limitations of the current threading model. In standard CPython, multithreading is cooperative for CPU-bound tasks. The interpreter forces threads to take turns holding the lock. This works reasonably well for I/O-bound operations (like network requests in Django async or FastAPI news aggregators), but it fails catastrophically for CPU-intensive tasks like image processing or Algo trading algorithms.

Asyncio vs. Multiprocessing vs. Free Threading

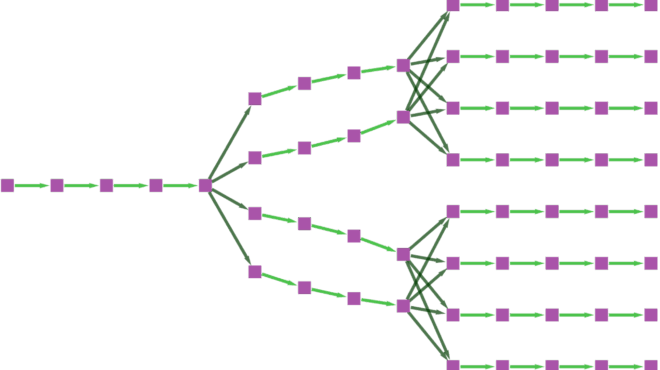

Developers have historically relied on two main workarounds:

- Asyncio: Great for concurrency (handling many connections), but limited to a single core. It uses an event loop to switch context during wait times.

- Multiprocessing: Spawns separate processes, each with its own memory space and GIL. This achieves parallelism but incurs heavy overhead for data serialization (pickling) and Inter-Process Communication (IPC).

The promise of free threading in Python 3.13 is to allow threads to run simultaneously on different cores within the same process, sharing memory without the serialization penalty of multiprocessing. This is critical for Local LLM inference and complex Python finance models.

Let’s look at a standard CPU-bound task that suffers under the GIL:

import time

import threading

def cpu_bound_task(n):

"""A simple function that burns CPU cycles."""

while n > 0:

n -= 1

def run_threaded(count):

start_time = time.time()

# Create two threads

t1 = threading.Thread(target=cpu_bound_task, args=(count,))

t2 = threading.Thread(target=cpu_bound_task, args=(count,))

t1.start()

t2.start()

t1.join()

t2.join()

end_time = time.time()

print(f"Time taken with threads: {end_time - start_time:.4f} seconds")

# In a GIL-enabled Python, this will not be 2x faster than running sequentially.

# In fact, it might be slower due to context switching overhead.

if __name__ == "__main__":

# 100 million iterations

run_threaded(100_000_000)In a standard Python 3.12 environment, the code above runs on a single core, switching rapidly between threads. With the experimental free-threading build of Python 3.13, these threads can execute in true parallel on separate cores.

Implementation Details: Under the Hood of PEP 703

Removing the GIL is not as simple as deleting a mutex. The GIL protected CPython’s internal state, particularly reference counting for memory management. Without it, race conditions would corrupt memory instantly. The implementation of free threading introduces several sophisticated mechanisms:

Immortal Objects and Deferred Reference Counting

Apple TV 4K with remote – New Design Amlogic S905Y4 XS97 ULTRA STICK Remote Control Upgrade …

To make the interpreter thread-safe without the GIL, two major changes were introduced:

- Immortal Objects: Objects like `None`, `True`, `False`, and small integers are marked as “immortal.” Their reference counts are never modified, eliminating the need for locking when accessing these frequently used singletons.

- Deferred Reference Counting (Biased Reference Counting): For other objects, the interpreter uses a technique where reference count updates are often local to the owning thread, reducing the contention on shared atomic operations.

This architectural shift requires significant updates to C-extensions. Libraries like NumPy news and PyTorch news channels have been buzzing with activity as maintainers update their internal C/C++ code to be thread-safe without relying on the GIL.

The JIT Compiler Integration

Python 3.13 also introduces a copy-and-patch Python JIT (Just-In-Time) compiler. While currently separate from the GIL removal effort, the synergy between JIT and free threading is where the future performance gains lie. The JIT can optimize bytecode execution, while free threading allows that execution to scale across cores.

Here is an example of how you might structure a modern, thread-safe worker using the new paradigm, keeping in mind that shared mutable state is now dangerous:

import threading

from concurrent.futures import ThreadPoolExecutor

import time

# A thread-safe shared resource using a Lock

# Even with GIL removal, you must lock shared mutable data!

class ThreadSafeCounter:

def __init__(self):

self._value = 0

self._lock = threading.Lock()

def increment(self):

with self._lock:

self._value += 1

def get_value(self):

with self._lock:

return self._value

def worker(counter, iterations):

for _ in range(iterations):

counter.increment()

def main():

counter = ThreadSafeCounter()

iterations = 1_000_000

workers = 4

with ThreadPoolExecutor(max_workers=workers) as executor:

futures = [executor.submit(worker, counter, iterations) for _ in range(workers)]

# In Python 3.13 free-threaded, the overhead of the lock remains,

# but the execution of non-critical sections runs in parallel.

print(f"Final count: {counter.get_value()}")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()It is crucial to note that GIL removal makes Python behave more like Java or C++. You are now responsible for thread safety. Tools like SonarLint python and Ruff linter will become essential for detecting race conditions in this new era.

Advanced Techniques: The Modern Performance Stack

While we wait for the free-threading ecosystem to mature, developers are already bypassing the GIL using modern libraries that implement their own parallelism in lower-level languages like Rust or C++. This “declarative” approach—telling the library what to do rather than how to loop—is often superior to manual threading.

Leveraging Rust and Arrow

The rise of Rust Python integrations has revolutionized data processing. Libraries like Polars dataframe and DuckDB python utilize PyArrow updates to handle memory efficiently. When you execute a query in Polars, it releases the GIL and uses the Rust thread pool to execute the operation across all available cores.

This renders the GIL irrelevant for data-heavy tasks. Here is how you can achieve massive parallelism today, regardless of your Python version:

import polars as pl

import numpy as np

def process_heavy_data():

# Create a massive DataFrame

# Polars handles memory efficiently using Arrow

df = pl.DataFrame({

"group": np.random.choice(["A", "B", "C"], 10_000_000),

"value": np.random.rand(10_000_000)

})

# This operation is fully parallelized in Rust, bypassing the Python GIL entirely.

# It utilizes SIMD instructions and multi-core execution.

result = (

df.lazy()

.group_by("group")

.agg([

pl.col("value").mean().alias("mean_val"),

pl.col("value").std().alias("std_val"),

(pl.col("value") * 2).log().sum().alias("complex_calc")

])

.collect() # Triggers execution

)

print(result)

if __name__ == "__main__":

process_heavy_data()This approach dovetails with the Ibis framework, which allows you to write Python code that compiles down to SQL or Polars expressions, effectively decoupling your logic from the Python interpreter’s limitations.

AI and The Edge

In the realm of AI, Keras updates and Scikit-learn updates are increasingly focusing on releasing the GIL for tensor operations. However, for Edge AI applications running on MicroPython updates or CircuitPython news, the constraints are different. While these embedded environments may not support full free threading yet, the optimization techniques learned from the desktop world are trickling down.

Furthermore, LlamaIndex news suggests that local RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) systems will benefit immensely from free threading. Indexing documents involves heavy text processing (CPU bound) and database writes (I/O bound). A free-threaded Python can handle the embedding generation and vector storage simultaneously without the complexity of multiprocessing.

Best Practices and Tooling for the Transition

Transitioning to a free-threaded world requires a robust toolchain. The days of simple `pip install` might get complicated as wheels need to be built specifically for free-threaded CPython (often denoted with a `t` ABI flag).

Modern Package Management

To manage these complexities, modern package managers are essential. The Uv installer (written in Rust) and Rye manager provide faster resolution and better environment isolation than traditional tools. They are better equipped to handle the compilation of dependencies that might be required for Hatch build or PDM manager workflows in a free-threaded environment.

Code Quality and Security

With great power comes great responsibility. Thread safety issues can lead to subtle bugs and security vulnerabilities. Python security is no longer just about PyPI safety and checking for Malware analysis in dependencies; it is about ensuring your own code doesn’t introduce race conditions that could be exploited.

You should strictly enforce Type hints and use MyPy updates to track shared state. The Black formatter ensures code consistency, but logic checkers are vital. Here is an example of using modern typing to clarify thread-safe intentions:

Apple TV 4K with remote – Apple TV 4K iPhone X Television, Apple TV transparent background …

from typing import List, Dict, Final

import threading

import time

# Using Final to indicate constants that are safe to share across threads

MAX_RETRIES: Final[int] = 3

class SafeDataStore:

def __init__(self) -> None:

# Explicit type hinting helps static analysis tools

self._storage: Dict[str, List[int]] = {}

self._lock: threading.Lock = threading.Lock()

def add_metric(self, key: str, value: int) -> None:

with self._lock:

if key not in self._storage:

self._storage[key] = []

self._storage[key].append(value)

def process_metrics(self) -> None:

# Snapshot data to minimize lock contention

with self._lock:

snapshot = self._storage.copy()

# Heavy processing happens outside the lock

for key, values in snapshot.items():

print(f"Processing {key}: average {sum(values)/len(values)}")

# Tools like Ruff can be configured to warn about locking patterns

# and complexity that might hinder parallel performance.Testing and UI Frameworks

For testing, Pytest plugins like `pytest-xdist` have historically used multiprocessing. With free threading, we may see plugins that utilize threads for faster test execution with lower memory footprints. This is particularly relevant for Selenium news and Playwright python suites, which are I/O heavy but benefit from parallel execution.

In the UI space, frameworks like Reflex app, Flet ui, and Taipy news rely on responsive backends. GIL removal ensures that heavy background logic (like running a Scikit-learn prediction) won’t freeze the UI thread, providing a smoother user experience without the complexity of async wrappers.

Conclusion: The Future is Parallel

The removal of the GIL in Python 3.13 marks a watershed moment in the language’s history. While it is currently optional and requires careful consideration regarding thread safety, it paves the way for Python to compete in high-performance domains previously reserved for Go, Java, or C++. It addresses the “scaling” complaints by allowing vertical scaling on multi-core machines without the memory bloat of multiprocessing.

However, the transition will not be overnight. For most users doing data science, relying on Pandas updates and the Polars dataframe ecosystem will continue to be the most effective way to achieve performance, as these libraries have already solved the parallelism problem internally. For application developers building Litestar framework APIs or Python quantum simulations with Qiskit news, free threading offers a simplified architecture where concurrency is no longer a choice between “slow” or “complex.”

As we look toward Python 3.14 and beyond, the integration of the Python JIT and mature free-threading support will likely cement Python’s position not just as a glue language, but as a high-performance runtime for the AI era.