Bridging Bits and Atoms: A Deep Dive into Archimedes and the Python Hardware Engineering Revolution

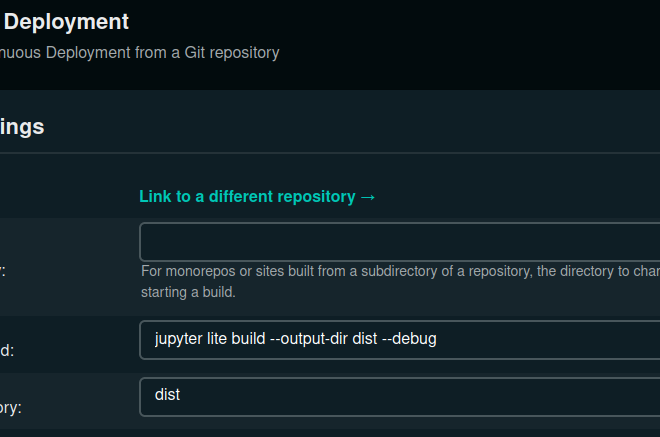

The landscape of software development is constantly shifting, but one of the most exciting developments in recent python news is the language’s aggressive expansion into the realm of hardware engineering. For decades, mechanical and electrical engineering workflows have been dominated by heavy, GUI-driven proprietary software. While effective, these tools often lack the flexibility, automation capabilities, and version control standards that software developers take for granted. Enter the new wave of “Code-CAD” and hardware toolkits, spearheaded by libraries like Archimedes.

This article explores the emergence of Python-based toolkits for hardware engineering, specifically focusing on the capabilities introduced by frameworks like Archimedes. We will examine how defining physical geometry through code is transforming manufacturing, the technical implementation of these libraries, and why this represents a paradigm shift for engineers who are ready to trade their mouse clicks for function calls.

The Convergence of Software and Hardware Design

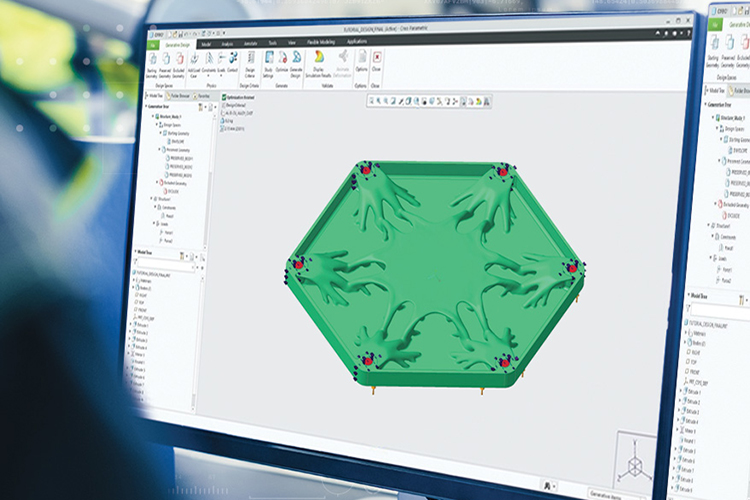

Traditionally, designing a physical component involves a Computer-Aided Design (CAD) interface where an engineer draws lines, extrudes shapes, and manually applies constraints. While intuitive, this process is difficult to automate. If a design requirement changes—for example, if a mounting hole needs to move 5mm to the right across 50 different files—the engineer faces hours of manual labor.

The latest python news highlights a growing trend toward “Hardware as Code.” This philosophy treats physical design descriptions as source code. By using Python to define geometry, engineers gain access to the entire software development lifecycle ecosystem: Git for version control, automated testing frameworks, and Continuous Integration/Continuous Deployment (CI/CD) pipelines.

Why Python for Hardware?

Python is the natural choice for this evolution due to its readability and massive ecosystem. A hardware engineer using a toolkit like Archimedes isn’t just drawing shapes; they are leveraging numpy for complex mathematical calculations, pandas for importing material data, and scipy for optimization algorithms. The ability to glue these distinct domains together makes Python the premier language for modern engineering.

The Core Philosophy of Archimedes

Archimedes and similar toolkits operate on the principle of constructive solid geometry (CSG) and boundary representation (B-rep) via an API. Instead of storing a binary file that describes a shape, you store a Python script that generates the shape. This ensures that the design is parametric by nature. A single variable change at the top of the script cascades through the entire model, updating dimensions, tolerances, and feature placements instantly.

Technical Breakdown: Modeling with Code

To understand the power of this approach, we must look at the code. In a GUI CAD tool, creating a plate with four holes involves drawing a rectangle, drawing four circles, adding dimension constraints, and extruding. In Python, this becomes a reusable class or function.

Below is a conceptual example of how one might define a parametric mounting plate using a hardware engineering toolkit structure similar to Archimedes. This demonstrates the transition from manual drawing to algorithmic definition.

from archimedes_mock_lib import Part, Sketch, Operation

import math

class ParametricMount(Part):

def __init__(self, width, height, thickness, hole_diameter):

super().__init__()

self.width = width

self.height = height

self.thickness = thickness

self.hole_dia = hole_diameter

def construct(self):

# Create the base profile

base_sketch = Sketch.create_rectangle(

width=self.width,

height=self.height,

center=True

)

# Define hole positions dynamically based on dimensions

# This ensures holes are always inset 10% from the edge

inset_x = self.width * 0.4

inset_y = self.height * 0.4

hole_positions = [

(inset_x, inset_y),

(inset_x, -inset_y),

(-inset_x, inset_y),

(-inset_x, -inset_y)

]

# Add holes to the sketch

for x, y in hole_positions:

base_sketch.add_circle(

center=(x, y),

diameter=self.hole_dia,

mode=Operation.SUBTRACT

)

# Extrude the 2D sketch into a 3D object

self.solid = base_sketch.extrude(amount=self.thickness)

# Apply fillets (rounded edges) to the main solid

self.solid.fillet(radius=2.0)

# Usage: Generating multiple variations instantly

standard_mount = ParametricMount(width=100, height=100, thickness=5, hole_diameter=4)

heavy_duty_mount = ParametricMount(width=150, height=150, thickness=10, hole_diameter=8)

# Export to STL for 3D printing

standard_mount.export("mount_std.stl")

heavy_duty_mount.export("mount_hd.stl")

Analysis of the Code

In the example above, the power lies in the dynamic calculation of inset_x and inset_y. In traditional CAD, changing the width of the plate might require manually updating the constraints of the holes to ensure they remain centered or aligned. Here, the relationship is encoded mathematically. If the width changes, the holes move automatically to maintain the design intent.

Furthermore, the object-oriented nature allows for inheritance. You could create a WaterproofMount class that inherits from ParametricMount but adds a groove for a rubber gasket. This level of reusability is virtually non-existent in traditional CAD file formats.

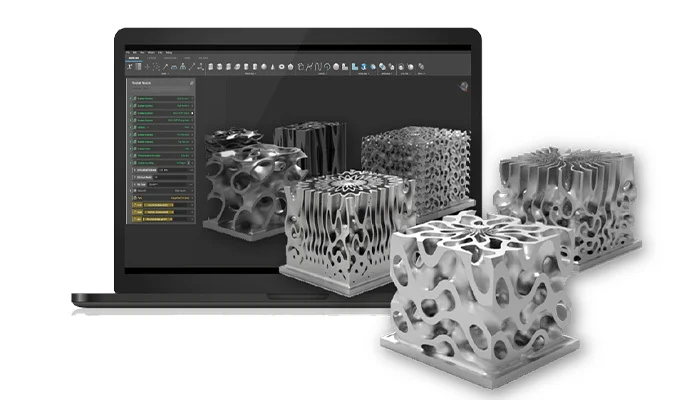

Handling Complex Geometries

While simple shapes are easy, Python toolkits excel at complex, mathematically defined surfaces. Imagine designing a heat sink where the fin density needs to vary based on a thermal simulation heatmap. Doing this manually is tedious. With Python, you can map a data array directly to geometry.

import numpy as np

def generate_variable_heatsink(base_size, thermal_map_data):

"""

Generates fins with varying heights based on thermal load data.

"""

base = Sketch.create_rectangle(base_size, base_size).extrude(2)

# Iterate through data to create fins

for i, row in enumerate(thermal_map_data):

for j, temp_value in enumerate(row):

# Higher temperature = taller fin

fin_height = map_range(temp_value, 0, 100, 5, 20)

fin = Sketch.create_circle(diameter=2)

fin_solid = fin.extrude(fin_height)

# Position the fin

x_pos = i * 5

y_pos = j * 5

fin_solid.translate(x_pos, y_pos, 2)

# Union the fin with the base

base = base.union(fin_solid)

return base

This snippet illustrates a workflow that is nearly impossible in standard CAD software without expensive plugins. It bridges the gap between simulation data and physical design construction.

Implications for the Engineering Workflow

The introduction of tools like Archimedes into the python news cycle suggests a broader shift in how hardware teams collaborate. The implications extend far beyond just “drawing with code.”

Version Control for Atoms

One of the biggest pain points in hardware engineering is version control. Binary CAD files (like .SLDPRT or .STEP) are opaque to version control systems like Git. You cannot run a “diff” to see what changed between Version 1 and Version 2; you simply see that the file size changed.

With Python-based hardware design, the design is text. A git diff clearly shows:

- self.width = 100

+ self.width = 120

This allows for code reviews on hardware designs. A senior engineer can review a Pull Request for a mechanical part, comment on specific lines of code defining tolerances, and merge the changes only when approved. This brings the rigor of software engineering to physical manufacturing.

Automated Quality Assurance (QA)

Software developers use Unit Tests to ensure their code works. Hardware engineers can now use Unit Tests to ensure their geometry is valid. By integrating Python’s unittest or pytest frameworks, engineers can write test suites for physical parts.

import pytest

from my_hardware_lib import ParametricMount

def test_mount_hole_clearance():

"""

Ensure that the mounting holes are never too close to the edge

of the material, which would cause structural weakness.

"""

# Create a mount with extreme dimensions

mount = ParametricMount(width=50, height=50, thickness=5, hole_diameter=20)

# Calculate distance from hole edge to plate edge

# (Logic would access internal geometry data)

edge_margin = mount.calculate_min_edge_margin()

# Assert that we have at least 3mm of material

assert edge_margin >= 3.0, "Hole is too close to the edge! Structural failure risk."

def test_volume_constraints():

"""

Ensure the part fits within shipping weight limits by checking volume.

"""

mount = ParametricMount(width=100, height=100, thickness=10, hole_diameter=5)

volume_cm3 = mount.solid.volume() / 1000

# Assuming Aluminum density approx 2.7g/cm3

weight_g = volume_cm3 * 2.7

assert weight_g < 500, "Part is too heavy for standard shipping."

This "Test-Driven Design" for hardware prevents invalid parts from ever being sent to the manufacturer. It catches errors at the design stage automatically, saving significant time and money.

The CI/CD Pipeline for Manufacturing

Imagine a workflow where pushing code to a GitHub repository triggers a GitHub Action. This action runs the unit tests, generates the 3D mesh (STL), generates the 2D technical drawings (DXF), and zips them into a release package ready for the machine shop. This is the reality enabled by Python hardware toolkits. It removes the manual step of "File -> Export -> Save As" for every single revision.

Pros, Cons, and Recommendations

While the excitement in recent python news regarding tools like Archimedes is justified, it is essential to view this technology through a critical lens. It is not a universal replacement for traditional CAD, but rather a specialized tool for specific workflows.

Pros

- Parametric Power: Unmatched ability to create variations of parts based on input data or mathematical formulas.

- Reproducibility: The code is the source of truth. There is no ambiguity about how a shape was constructed.

- Automation: Easy integration with other Python libraries for optimization, data processing, and file management.

- Collaboration: Enables the use of Git, Pull Requests, and code reviews for hardware design.

- Cost: Many of these tools are open-source, contrasting with the expensive licenses of professional CAD suites.

Cons

- Visualization Latency: Unlike GUI CAD, where you see the shape as you draw it, code-based CAD often requires a "compile and render" cycle to see changes, though live-reload viewers are improving.

- Learning Curve: Mechanical engineers must learn software development concepts (classes, inheritance, git) to use these tools effectively.

- Complex Assemblies: Managing massive assemblies with thousands of parts solely through code can become unwieldy compared to the visual assembly trees in SolidWorks or CATIA.

- Filleting and Chamfering: These operations are notoriously difficult in geometric kernels. While GUIs handle edge selection intuitively, selecting specific edges programmatically can be fragile if the topology changes.

Recommendations

For engineering teams looking to adopt this workflow, the best approach is hybrid. Use traditional CAD for complex, organic surfaces or massive assemblies where visual spatial reasoning is paramount. Use Python toolkits like Archimedes for:

- Standard Parts: Gears, brackets, enclosures, and spacers that follow strict mathematical rules.

- Data-Driven Design: Parts that must change dimensions based on external datasets (e.g., custom prosthetics based on 3D scans).

- Electronic Design Automation (EDA) Integration: Generating 3D models of PCB components automatically.

Conclusion

The emergence of Archimedes and similar toolkits marks a significant milestone in python news and the broader engineering industry. By decoupling design from proprietary binary formats and embracing the "Hardware as Code" philosophy, engineers can unlock levels of automation and reliability previously reserved for software development.

As Python continues to cement itself as the lingua franca of the technical world, the barrier between the digital and physical continues to dissolve. For the hardware engineer of the future, the most powerful tool in the toolbox might not be a caliper or a wrench, but a well-structured Python script. Whether you are designing a simple bracket or a complex parametric assembly, the ability to define the physical world through code is a superpower that is reshaping the manufacturing landscape.